Washington & Baltimore

Battle of Bladensburg — Burning of Washington — Bombardment of Fort McHenry

With the end of hostilities on the Continent, albeit temporary, Great Britain was free to focus its military attention more fully on its North American conflict. Though the Royal Navy’s North American station, now under Commander Sir Alexander Cochrane, remained under-staffed for enforcing the blockade of U. S. ports, its practice of frequent small raids inland was having an impact. Rear Admiral George Cockburn led this more aggressive strategy, in the summer of both 1813 and 1814, burning buildings and seizing thousands of pounds of stores.

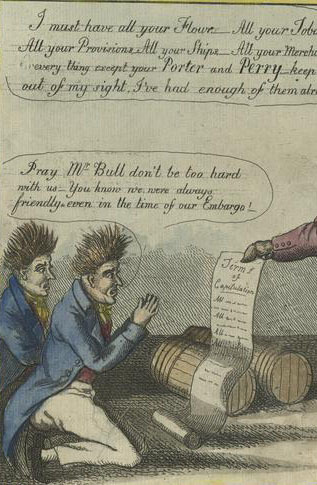

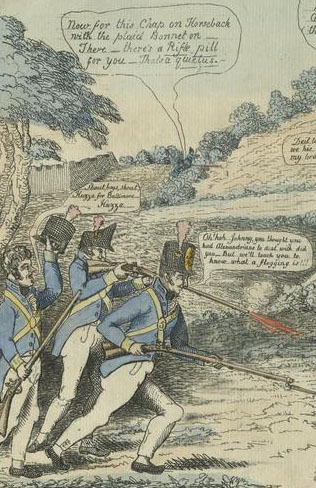

Cochrane and Cockburn worked with Major General Robert Ross to plan and execute a dramatic series of operations in the Chesapeake Bay that culminated in the burning of the U. S. capital. After a series of smaller raids, Cockburn and Ross brought troops up the Anacostia River, north of Washington, and advanced toward the capital. Washington was poorly defended, having not been thought a likely British target. Its defense relied principally on militia, and its command was less than effective with Secretary of State Monroe interfering with the deployment of troops commanded by Brigadier General William Winder. On August 24, 1814, British troops met up with militia defenders at Bladensburg, about eight miles northeast of Washington, and quickly dispersed the defenders, a situation later satirized as the “Bladenburg Races.”

British troops pushed on to Washington which was nearly deserted, most residents having fled. Ross’s troops burned public buildings, including the White House. The burning of government buildings is sometimes framed as revenge for the U.S. burning of the parliament building in York in 1813, but burning was part of Cockburn’s normal operations and there was no official leadership left in Washington to broker a more peaceful surrender. Holding the U.S. capital was not of any particular military importance, so British troops withdrew to waiting ships and prepared for further attacks along the Bay.

Baltimore was the next British target, and it mounted a more formidable defense. Wealthy with maritime interests and home to many American privateers, Baltimore was also known for perhaps the most anti-British sentiment of all American cities. Major General Samuel Smith had involved nearly the whole city in building defensive earthworks and surrounding the city with close to 10,000 men including sailors and marines under the command of Commodore John Rodgers. When the British landed at North Point on September 12, they encountered a force of militia that inflicted serious causalities and killed their leader, General Ross, but did not stop the British advance.

Once at Baltimore, British commanders knew they needed naval artillery support to weaken the extensive defenses. But to reach the city, the British squadron needed to get past Fort McHenry, a substantial fortification that guarded the water approach to the city. For twenty-five hours five bomb ships and one rocket ship of the British squadron hurled everything they had at the fort, but failed to destroy or disable the defenses and open up the waterway to Baltimore. The British withdrew, on both land and sea the morning of September 14. The dramatic overnight bombardment inspired a young attorney, who viewed the conflict from some remove on board the U.S. ship President, to write a song celebrating the American victory. First titled “The Defense of Fort McHenry”, it is now known as the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

Related Items

Plans to attack New York, Baltimore, and Washington

Letter from Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane to Lord Melville. July 17, 1814.

In this long letter, Cochrane outlined potential plans for the attack of a number of American cities, including New York (page 3, image 4) and Baltimore and Washington (page 8, image 9). He wrote: “In an an attack on Baltimore I count upon being joined by a number of Negros.”

Cochrane describes burning of Washington

Letter from Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane to Sir Richard Hussey Bickerton. August, 1814.

Writing to a fellow admiral, Cochrane described the victory: “I have but a moment to tell you that we have destroyed the Baltimore Flotilla under Commodore Barney—Defeated the American Army twice our numbers, taken all their cannon—Turned the little President out of his Capitol—Burned the Capitol, President’s Palace, Naval and Military Arsenals, a huge frigate of the largest class and a sloop of war, all their stores, public buildings &&& Almost to the tune of 12 millions sterling and returned 50 miles through a populous enemy country without a shot being fired.” Read Cochrane’s accounts of victory at Bladensburg and defeat at Baltimore.

What to do about Washington, D.C.?

Letter from Richard Stanford to Harmanus Bleecker. September 26, 1814.

Stanford, a member of Congress from North Carolina wrote to Senator Bleecker: “So far as I can judge (for no question has arisen to show the course the opposition might pursue) there will be more union in future than has heretofore appeared since the war. It will be the result of necessity under existing circumstances and not a matter of choice. This disgraced place may continue to be the seat of government. I think it suits their character well, but a question is made, whether it is, or is not to be, and in a few days I presume we shall know.”

A letter from a soldier to his mother

Letter from James M. Varnum to Mary Varnum. August 31, 1814.

Soldier James Varnum wrote of the burning of Washington: “Our general was so panic struck he marched the troops fourteen miles from the city. The enemy found that our general was frightened—Admiral Cockburn and Major General Ross marched in the city at the head of about 200 men and walked thro the streets of Washington with two or three guards with as much safety as if they had been in London.”