Politics & Peace

Peace negotiations - The Hartford Convention

President Madison officially accepted the British offer of direct peace negotiations in January 1814. He sent two more members to join the peace delegation, Henry Clay and Jonathan Russell, who arrived mid-April, after a harrowing sea voyage. The spring of 1814 also brought the abdication of Napoleon which marked a pause, if not the end, of what had seemed an interminable war on the Continent. The end of hostilities in Europe was a key development that pushed forward peace negotiations. On the American side, leaders quite rightly saw that the North American war would soon have the full attention of Great Britain. The British side, on the other had, suffered from fatigue and financial instability wrought by many years at war.

By mid-summer the U.S. dropped its opposition to British impressment. The practice was already on the wane, and peace between Britain and France promised further diminishment of impressment. The five member U.S. delegation met with British representatives starting on August 8. The British negotiators were Admiral Lord Gambier, Henry Goulburn, and William Adams, who worked in close contact with Secretary of War and the Colonies Lord Bathurst who coordinated the talks with Prime Minster Lord Liverpool and the diplomatic leaders handling the post-war settlements in Europe.

Once the impressment issue was off the table, negotiations revolved around territory. The U.S. advocated a return to pre-war territorial divisions while Britain sought territorial concessions in the north and a buffer state set aside for Native Americans in the Old Northwest. By the time a treaty was signed, on December 24, the two sides agreed to a return to pre-war boundaries and the buffer state was watered down to a toothless article governing the fair treatment of Indians, which the United States subsequently ignored.

Even as the peace treaty was being finalized, American opponents to the war met to discuss their grievances and propose political remedies to prevent future wars. The gathering brought Federalist representatives drawn from the legislatures of five states to Hartford, Connecticut, to meet in secret session. The Hartford Convention’s final report endorsed checks on presidential power and the power of the southern states, but the meeting was characterized by Democratic opponents as a seditious gathering designed to craft a plan for the secession of the New England states. The secessionist interpretation stuck, and the Hartford Convention signaled the beginning of the demise of the Federalist party.

Related Items

British negotiating priorities

Nathaniel Atcheson. A compressed view of the points to be discussed, in treating with the United States of America : A.D. 1814, with an appendix and two maps. London: J.M. Richardson, 1814.

In advance of peace negotiations, this British book outlined a variety of issues subject to negotiations, beyond the basic conflict over impressment and maritime rights. The retention of the colonies in Canada and the protection of Indian rights are the first two subjects discussed.

He's not complaining, but...

Letter from Admiral Alexander Cochrane to Lord Melville. March 25, 1814.

Newly arrived to take command of the North American station, Cochrane wrote in this letter of his plans for the Chesapeake Bay campaigning and other matters, but also of his frustration with Sir John Warren who was refusing to transfer command. “…so far as my enquiries have gone I think there is every prospect of success and had Sir John Warren placed me in command of the squadron upon my arrival considerable progress would have been made in the preparations previous to the arrival of the troops. Although I by no means wish this letter to bear the language of complaint…”

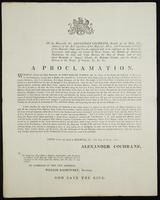

Extending the blockade

Admiral Alexander Cochrane. A proclamation. April 25, 1814.

Cochrane issued this extention of the blockade of the American coast after attempts to engage anti-war forces in New England failed. The British blockade now stretched, in addition to its existing boundaries, “from the Point of Land commongly Black Point to the Northern and Eastern Boundaries between the said United States and the British Province of New Brunswick in America…”

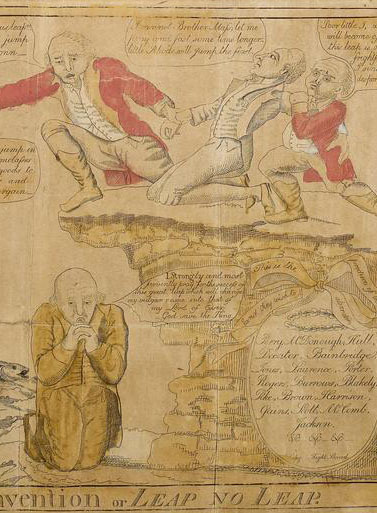

Mocking the Hartford Convention

William Charles. The Hartford Convention, or Leap No Leap. 1814.

In this popular print, critical of the Hartford Convention, King George encourages Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island to “leap” or secede. Federalist leader Thomas Pickering is depicted praying for the “success of this great leap” and in the upper left, three tiny men represent a Massachusetts delegation sent to Washington to negotiate the question of succession. Faced with an angel heralding peace, they exclaim, “Oh Lord! Oh Lord! We’re all Undone!”

Official report of the Hartford Convention

The proceedings of a convention of delegates, from the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode-Island; the counties of Cheshire and Grafton, in the state of New-Hampshire; and the county of Windham, in the state of Vermont. Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1815.

In this second edition of the published proceedings of the Hartford Convention, the reader can easily see how the discussion of the possible dissolution of the union (page 5) could be used against the Federalists. Though they wrote that such a break-up “should, if possible, be the work of peaceable times, and deliberate consent,” the text went on speculate further on dissolution. The resolutions of the Convention are found on page 21.