The USDA and the Motion Picture Service

The USDA formed in 1862 as its own agency within the federal government. The first head of the agency, called the Commissioner of Agriculture, was Isaac Newton, a farmer from Pennsylvania. Newton was also involved with the nongovernmental United States Agricultural Society, which has been claimed as a precursor to the USDA.16 The USDA was formed alongside the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act which gave land rights to the formation of colleges for agricultural studies, and likely only came to existence after the Confederate revolt eliminated pressure against the measures from the South.17 Much of the early USDA’s responsibilities consisted of supplying seed packets for citizen requests, providing education on agricultural and rural health and living, and statistical gathering of agricultural data.18 By the 1880s, the USDA came to include the Division of Forestry to oversee the nation’s enlarging national forests and grazing lands. The following decades would see the continual growth of the agency to its basic resemblance of today's USDA.

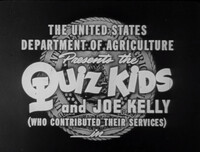

USDA films often partnered with other government agencies and even private companies, like the beginning of The Gardens of Victory shows.

Another large addition to the agency came during the Great Depression expansion of the federal government. The USDA grew to include the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) in 1933 as part of a large omnibus spending bill. The AAA gave the USDA a larger budget and more direct control of agriculture prices in light of the serious agriculture price struggles of the era. The program added greater economic control to the agency to go along with their other missions of research and education. Their powers included stabilizing and increasing the price of agricultural products and balancing import and export controls of farm commodities.19 Finally, a solution was created for the overproduction challenges farmers put themselves into as they tried to increase their incomes. Other money was dedicated to documenting and studying the Dust Bowl disaster.20 While some other agencies started as independent from the USDA, by the late 1940s, the USDA would encompass the responsibilities of the Soil Conservation Service, the Resettlement Security Administration, the Commodity Credit Corporation, and the Rural Electrification Administration.21 By the end of the Great Depression, the rough form of the modern USDA took shape.

With greater objectives and budgets, USDA activities expanded. Research was growing and increasingly taking place at publicly funded universities and within the government. To enhance education and interaction with communities, the USDA had a large number of agricultural extension offices. These offices were controlled by local extension leaders, to dispense the latest information to local farmers and ranchers on increasing yields and herd health, improving living conditions, and explaining available programs to citizens. Among notable objectives was the push to control the cattle fever tick.22 During WWII, these extension offices would become vital for the organizing of volunteer labor drives for harvests, keeping track of agriculture statistics, dispensing propaganda on rationing and other government restrictive efforts, and the communication of draft furloughs for local agriculture workers.23 The USDA took a lead role in maintaining and increasing food production for overseas soldiers and to satisfy the growing needs of America’s allies. By 1944, the USDA successfully encouraged the harvest of 380 million acres by U.S. farmers, making it the largest acreage of harvest on record to that point.24

The level of success the USDA achieved came partially from the USDA Motion Picture Service (MPS). The origins of the MPS date back to the early 1900s. While specific claims are not without doubt, for example the USDA being the first government agency to make a motion picture, what is understood is that the USDA was an early adapter to the film medium and was producing films out of a designated film lab by 1912.25 From the beginning, the MPS made films with an educational purpose, teaching the American public what the many departments within the USDA were responsible for and providing information to audiences for their own educational benefit. Films were shown a few different ways. Local theaters often showed MPS films before featured motion pictures alongside short newsreels. Extension agents also toured throughout the U.S. on trucks equipped with projection equipment. These trucks allowed for MPS films to be played anywhere. Consequently, many rural Americans had their first experience with motion pictures from these gatherings.26 Extension agents without projection trucks often loaned MPS films and organized viewings at local schools, churches, auto dealerships, or community centers that already had the necessary projection equipment.27 Organizations and individuals could also loan films directly from the USDA or from universities as the USDA supplied higher education institutions with films to lend.28

The success came immediately for the MPS. Extension agents reported gatherings with motion picture showings garnered larger audiences than those without showings.29 By 1923 the audience viewership totaled 4.5 million, although accurate counts are hard to determine since the data was reliant on local agents and head count estimates.30 The large and wide ranging departments within the USDA allowed for variety and high numbers of MPS films, a partial credit to continued audience turnout.31 Loan requests often had to be turned down due to demand. 1929 proved to be highly important for the MPS, new equipment allowed for the creation of talkies, or motion pictures with sound. Further, that same year the USDA began selling film copies, with purchases made to other countries including: Japan, India, Russia, and Mexico.32 Over the next decade, audiences grew to an excess of five million people by 1938.33

Connections to family members and friends serving in the war helped to create urgency to action, as this shot from The Farmer's Wife shows.

The onset of World War II changed much for the MPS. The division saw several temporary staff relocations to assist with other government motion picture projects, which hindered production.34 The emphasis within motion pictures also changed due to the war. Much of the attention shifted to highlighting the drives for rationing materials critical to war efforts, organizing scrap metal or harvest drives, participating in the wartime labor force, or the encouragement for farmers and the general population to increase food production. These films, usually between seven and 20 minutes, stressed one’s patriotic duty to reduce consumption of goods and food.35 Like previous MPS films, these were shown frequently at schools, churches, and other communal settings. Many films directly connected actions and personal responsibilities of civilians in the United States with fighting to create urgency for action. For instance, the 1945 film Victory Harvest, referred to teenagers at school as “soldiers of the soil” while encouraging participation in volunteer harvest organizing.36 Other films played on the heartstrings of family members of those serving in the military, like the mother figure in The Farmer’s Wife who longingly looks at the pictures of her sons in uniform on the mantle between shots of extra hours worked on the family farm.37 Some films appealed to the moral responsibility to feed the world, which was facing severe food shortages due to fighting; The Gardens of Victory directly stated this to the audience, “Now half the civilized world looks to our nation to keep from starvation and death.”38 A common wartime subject was the planting of personal or community gardens. Entire MPS films were dedicated to providing everything a layperson needed to know about growing produce, including types of fruits and vegetables to grow, how to organize plants, watering schedules, harvest tips, and even how to store and can for long term usage. After WWII the MPS had difficulties recovering, and by 1958, the MPS appeared to have ceased operations.39