The Office of Education

The Office of Education would help to advertise valuable continuing education for Americans, as this scene demonstrates.

The Department of Education, later renamed the Office (or Bureau) of Education and then back to the Department of Education, was founded in 1867 to advise and report on the state of America’s education system at the federal level. From the debates surrounding the bill to establish the Department of Education, the would-be entity was a battleground between states’ rights and federal supremacy supporters. This was due to the historical precedent of individual states being in charge of education, which originated from the founding fathers leaving educational matters out of the Constitution. As the Civil War drew to a close Republicans in Congress seized on the opportunity to form a federal level education institution as many states’ rights supporting Democrats were not seated due to the war and Reconstruction.16 Additionally, a common perception held by northerners was that the root cause of the Civil War was the elevated levels of illiteracy in the South, a problem viewed to be compounded by the recent freeing of mostly uneducated slaves.17 The key to a healthy democracy was thought to be through education. Even with a muted Congress, debate on the legislation establishing the Department of Education was fierce. The bill had to be introduced twice, with Congress only agreeing to a limited version of the would-be entity which was still almost vetoed by President Andrew Johnson after Congressional passage. The expansion of the Department of Education over its more than 150 year history would thus be a slow process, as states were reluctant to cede authority.

The compromise legislation establishing the Department of Education created a small entity with limited direct power. Chiefly aimed at compiling statistics on education within the U.S., the new government entity held little power to enact meaningful change. The goal was to get a sense of educational outcomes and to shine spotlights on higher achieving areas of the country to be examples while also discussing low achieving regions to encourage change; ultimately relying on shame to motivate educational progress.18 This would all be on display in the yearly report published by the Department of Education, in effect its most meaningful tool. The staff and budget of the limited Department fit the powers it wielded, as Congress only funded a commissioner and four secretaries to carry out the entire mission.19 Conflict between Congress and Henry Bernard, the first Commissioner of Education resulted in an early cut to three workers and the commissioner for the entire operation as well as a demotion from a department to the Bureau (or Office) of Education under the Department of the Interior.20 The low budget and power would be a continuing theme until the mid-1900s, making the top education position in the United States a surprisingly hard to fill.21

Reshuffling within the federal government brought the Office of Education under oversight of the Federal Security Agency.

Heading into the Great Depression in 1929, the Bureau of Education was still a relatively small government entity, publishing annual reports, delivering speeches, and only having direct control over indigenous schools in the territory of Alaska. Just two years later, in 1931, the Bureau of Education transferred its Alaska responsibilities over to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. When transferring its responsibilities, Alaskan educational concerns accounted for around half of the annual budget for the entire Bureau of Education.22 Besides separating ties to Alaskan education, the early years of the Great Depression saw few noticeable changes outside of budget cuts for the Bureau.23 When newly-elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt came into office, there was hope for expansion within the Bureau of Education as part of New Deal legislation, but education was a lower priority for President Roosevelt and the Bureau was largely left out of programs in favor of direct employment initiatives.24 There was some collaboration with other New Deal programs, like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, to create education components to accompany their objectives but such efforts were limited.25 Reorganization in 1939 brought the renamed Office of Education under the Federal Security Agency, a bureaucratic reshuffle that housed government entities that otherwise did not have a large enough presence or clear placement in relation to other entities to be standalone agencies.26 By the end of the decade, the Office of Education was still a small entity, but this would soon change with World War II. Wartime drafting and industrial needs led to a boost to hiring. For many of these workers it was the first position taken outside the home or within manufacturing and heavy industry. In order to educate and train workers, Congress gave millions to the Office of Education to make sure critical wartime production remained steady. Over the course of the war, over half a billion dollars went to the Office of Education to fund everything from welding classes to training films for new and existing managers and even the creation of a Division of Inter-American Educational Relations to encourage democratic and pro-America views in South and Central America; all of this from a government entity that never handled more than a few hundred thousand dollars per year outside of an occasional management of a few million dollar land grant college account.27 War, not major unemployment cycles or educational reformers, proved to be the catalyst for growth for the Office of Education.

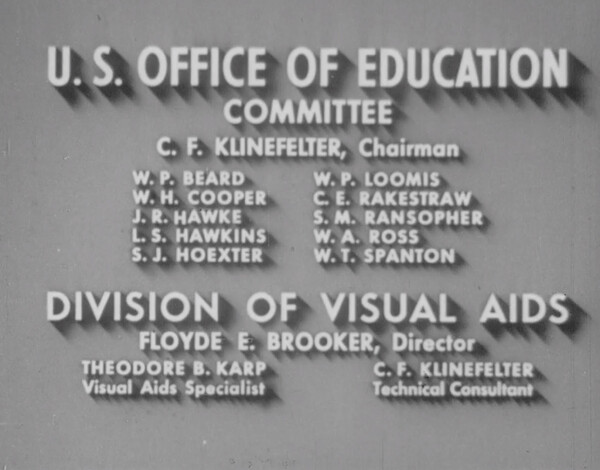

With wartime funding, the Office of Education expanded and created the Division of Visual Aids to oversee educational film production.

Although the Department of Education had hopes for continuing momentuem, large-scale support for the education at the federal level would not come for another few decades. Soon after the war, Commissioner John Studebaker called for a jump from around 200 employees to 1353, but only about 10 percent of these potential positions would have funding five years after the proposal. While that growth may seem ambitious, a 1353 person federal entity would have still been smaller than the New York State Department of Education at the time.28 Although expansion did not materialize as expected after World War II, the threat of another war, this time with the U.S.S.R., would finally prompt Congress to appropriate money towards the Office of Education. In 1958, the opportunity to tour U.S.S.R. educational institutions led to the creation of a comparative report in 1959 by the Office of Education. Fearing falling behind their enemy in critical areas of science and technology, as the U.S.S.R. was claiming victories in the space race, politicians began turning to the Office of Education for solutions.29 By 1960 the annual budget ballooned to over $500 million a year.30 Arrival of President Lyndon B. Johnson and his Great Society legislation, which emphasized education and social services, directed even more towards the Office of Education. Thanks to President Johnson, nicknamed the “Education President,” the 1966 Office of Education budget was a healthy $3.62 billion.31 Armed with money, personnel, and presidential backing, the Office of Education was a little entity no more, and became heavily involved with things like desegregation of schools and curriculum development.32 By the end of the 1960s the Office of Education came to prominence and would sustain itself for decades to come.

Although the modern Department of Education, which was granted the cabinet-level status of department in 1980, is greatly expanded in role and size today, elements of the past roles and debates surrounding the Office of Education are still evident. Given large increases in funding, the Department of Education is capable of more than just releasing annual reports to shame underperformance into change. Now, through recent programs like No Child Left Behind, the Department can encourage education styles, metrics, or other changes by the provision or withholding of federally earmarked funds. Still, as preceding the Office of Education, individual states still hold significant power in deciding their own educational destinies. As Goodwin Liu, a Professor of Law at the University of California and education scholar, explains, states still hold most power, “The result has been a patchwork of state standards and assessments that vary considerably in content, ambition, and rigor.”33 Moreover, states are in control of making many of the rules governing the requirements for grants and can opt out of many programs in favor of state funding.

The series taught a variety of skills to supervisors, often by modeling what not to do like being a micro-manager.

Cliches of educational films can be found, including this shot from Maintaining Quality Standards which features "Billy" the kid with a narrator.