The Era

Food once again became a strategic resource in WWII, and the U.S. was tasked with feeding not just its own troops but millions of other soldiers and civilians.

The United States was greatly impacted by the Great Depression which started a decade before World War II and still had lingering impacts by the U.S. entry into WWII. While signals of a weakening economy were showing beforehand, the stock market crash on October 29, 1929, a day referred to as Black Tuesday, began the Great Depression. Soon, the effects spread to more than just Wall Street. The unemployment rate rose rapidly, peaking at 31.4 percent in 1932.1 Fearful and in need of cash, Americans demanded their money from banks in mass exodus, forcing banks to call in loans and to tighten lending requirements. This often resulted in the closing of banks.2 After an initial response of fiscal tightening by the Hoover administration, the 1932 election brought Franklin Delano Roosevelt into office to start a series of federal programs to boost the economy. These programs were collectively referred to as the New Deal, and included many aspects of work Americans still enjoy today, like Social Security and unemployment insurance. Programs such as: the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and the Civil Works Administration (CWA) focused on putting unemployed Americans to work. Meanwhile Cash-strapped Americans turned to gardening on public and private land, called relief gardens, to aid struggling food budgets and maintain healthy diets.3 While government efforts were helpful, the economy still suffered lasting effects by the time WWII broke out in 1939. For instance, the U.S. unemployment rate still hovered over 17 percent when European hostilities broke out.4

The increasing amount of farm machines, like this peanut separating device, quickly became necessary purchases to farmers.

The economic and environmental conditions for U.S. farmers were devastating during this era. The imploding economy dropped demand for already struggling agriculture prices. The situation was compounded due to a failure to scale production back, which farmers made worse by increasing production in hopes of raising their total incomes. This dropped agricultural income by 65 percent.5 Banks, worried about their own financial situations, tightened lending practices and foreclosed on farmers when they fell behind on mortgage and other loan payments. With the transition to mechanized farming, many farmers required additional loans outside of mortgages in order to finance tractors and attachments. Foreclosures were so common that frustrated local farming communities would band together and buy back foreclosed properties at auction for low rates, through intimidation or threats of violence against higher bidders; these would become known as penny auctions. Intensifying the challenge for farm survival was the severe drought conditions impacting the Great Plains region through the 1930s. Referred to as the Dust Bowl or the “Dirty Thirties,” years of drought and a lack of adequate soil conservation from overharvesting and overgrazing dried out soil and increased erosion.6 All of these issues, combined with an African American movement towards northern cities, contributed to the migration of Americans from rural to urban areas, between the end of World War I in 1918 to 1940. During this time the percentage of Americans living in rural areas dropped from 48 percent to 43.5 percent.7 For more than a decade leading up to American entrance into World War II, being an American farmer involved significant struggle.

While the start of World War II began with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, the United States remained out of the conflict initially. Although not directly declaring hostilities with the Axis powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan, the U. S. began shipping critical war supplies to the Allies starting in March of 1941, with the Lend-Lease Act.8 A vital part of the Lend-Lease Act materials were foodstuffs, and soon the federal government was buying large quantities of agricultural products for overseas distribution. A welcome boon to American farmers and ranchers after years of low prices. The results were significant for both farmers and the war effort. For example, in 1941 the program gave Great Britain 29.1 percent of its entire food supply.9 The supplies were a much needed relief, that is if German naval vessels didn’t intercept the shipment during transit. Later that year in December, the United States formally entered the war in response to the Japanese surprise attack on the American fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor.

German u-boats were a serious threat to American shipping to Allies, even before entrance into the war.

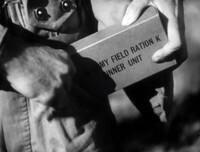

American life on the home front saw some stark adjustments during the war. Due to the food and supply needs of the U. S. military and its allies, a system of rationing was implemented. The list of rationed items was extensive and included clothing, gasoline, meat, canned food, and cars. For common consumables. like gas and meat products, the public was issued ration booklets. Moreover, the federal government instituted wage and price freezes and no-strike pledges to keep stability and productivity constant.10 With a focus on military production, the War Production Board limited sales of durable goods by a third in the first year of declared war and another 50 percent the year after.11 In contradiction to the limiting of available goods, advertisements saw a noticeable increase during the war, as companies flush with war contracts allocated money to marketing that otherwise could possibly have been taken due to wartime taxes of excessively high incomes.12 With men being drafted and sent overseas, ads and propaganda appealed to women, the primary consumers, to limit purchases, buy war bonds, and to plant gardens at home to ease food scarcity.13 Even with appeals to limit purchases, the wartime economy soared, making for a 25 percent inflation rate between 1940 and 1943.14 Women were also asked to take on additional responsibilities in paid labor outside of domestic home duties to aid the war production effort in industrial, farming, and other positions. Overall, the American economy created 17 million new jobs due to the war effort.15 While exciting changes were happening not everyone was able to participate in the home front equally, minorities faced internment camps, discrimination, and exclusion. The WWII home front was complex and rapidly evolving, with lasting impacts for decades to come.

With the onset of war canned food products became highly desirable, like this meat substance believe it or not.

Crops also had a plethora of non-edible war uses too, like soybean oil being used to paint warships.