The Era

World Events

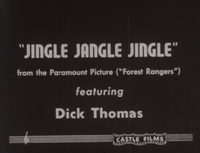

Providing visuals to music, Soundies would give Americans easier access to short films. The live bands of the 1930s would soon have a place on the Panoram in the 1940s.

The time period leading up to and incorporating the Panoram and its musical short films called Soundies greatly influenced the development and demise of the musical machine. One of the most critical events was the long-lasting Great Depression, which impacted the spending opportunities and habits of investors and the general public alike. Officially beginning with the stock market crash on October 29, 1929, otherwise known as Black Tuesday, the Great Depression would reverberate throughout the U.S. economy. Quickly after the stock market tanked, the broader economy of the United States plunged into despair. A worldwide event, the Great Depression would linger, with many places not seeing full economic recoveries until, or after, the outbreak of World War II in 1939. In the U.S., the unemployment rate would spike to 31.5 percent in 1932, and remain elevated for the entire decade.1 Due to the lack of jobs, many Americans lost their homes and were forced to bread lines and makeshift shanty encampments nicknamed “Hoovervilles” for President Herbert Hoover. To break free of the Great Depression, newly-elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created massive spending programs, to employ out of work Americans and raise the economic outlook. Given the economic problems, Americans lacked disposable income and investors were reluctant to fund new endeavors.

The wartime drives to support the troops could sometimes include unique ways to raise funds.

Still struggling with economic uncertainties, the outbreak of World War II created new challenges for U.S. entrepreneurs contemplating the launch of new audiovisual devices. The war, which started on September 1, 1939, with the German and Russian invasion of Poland, was initially a matter of neutrality for the U.S. While officially neutral, by 1941 the U.S. was sending war supplies to the Allies through the Lend-Lease Act and were increasing hostilities with the Axis powers of Germany, Japan, and Italy.2 Stringent restrictions on strategic wartime resources would be implemented after direct war was declared against the Axis powers after the surprise attack by the Japanese navy on the American fleet stationed in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Due to war needs many goods and raw materials were rationed, everything from gasoline, meat, and canned foods for the public and a plethora of raw materials like aluminum and rubber were scarce or virtually non-existent for private industry.3 Durable goods saw significant declines, with sales dropping by a third during the first year of the war and plunging another 50 percent the following year.4 While wartime labor demands created 17 million new jobs, advertisements and government propaganda stressed the limiting of purchases and the funneling of savings into war bonds.5 Yet even so, the period saw high inflation, over 25 percent from 1940 to 1943, due to limited goods and services available to the enlarging labor market.6 For potential businesses, gathering the resources to launch and deliver products was challenging, but if products could be built, consumers were eager to purchase.

Audiovisual Entertainment

Some Early Soundies would mimic radio studios for their performances, like this shot of the ending of "I Understand."

During the 1930s and 1940s, audiovisual entertainment and the audiovisual equipment used to create it, progressed rapidly. By 1930 watching high production films within movie theaters was a common activity for Americans. Even with falling discretionary spending due to the onset of the Great Depression, movie theater attendance actually increased during the first year of the economic slowdown and stayed strong throughout the 1930s, with American movie theater attendance ranging from 60 to 90 million per week.7 Films were a way to escape the harsh realities of the times, but also with regularly released newsreels showing before films, a key way to keep abreast of current events. While beginning as a formal practice around 1910, newsreels and the later “newsdramas,” like The March of Time, were mainstays for theater goers, providing brief, regularly-updated news digests with high visual appeal.8 High attendance numbers would continue throughout the 1940s as pre-movie newsreels displayed the latest war updates and footage to audiences.9 This era of cinema, from the 1920s through the 1940s, saw rapid expansion and the hieght of film attendance before other entertainment forms started to compete. The number of movie theaters operating in the U.S. would reach a peak in 1945 at 19,065 before dropping by about 50 percent just 18 years later in 1963.10 Whether for escape or news updates, clearly Americans loved the silver screen and would cut just about any other line item in their budgets before restricting their access to motion pictures.

Soundies would later feature many jazz artists, including this shot of three of the four Mills Brothers.

One of the emerging competitors to movie theaters was the expanding small gauge film scene. Advertised to amateur film enthusiasts, 16mm film and equipment was smaller and more affordable than 35mm film, making it an expensive but realistic purchase for middle class Americans and aspiring entrepreneurs. 16mm film was also made from acetate bases, making it less flammable compared to 35mm nitrate film. Nitrate fire is unaffected by water and can only be extinguished by burning itself out, making it dangerous and potentially deadly in enclosed environments. The realities of nitrate film required preventive measures to provide safety for the audience and crew. Special placement of film projectors, fire resistant projection booths, and other safety measures were required when showing nitrate film to the public.11 Even so, nitrate fires were not uncommon, and could be quite deadly. While pre-1948 acetate-based film in the U.S. had durability issues, they did not pose the same flammability risks and were often branded as “safety film”.12 Smaller, cheaper, and safer, 16mm film opened new opportunities for showing moving images in more places than the confines of traditional movie theaters.

Moving images were not the only form of entertainment technology to see important developments in the first few decades of the twentieth century. Audio technology also advanced rapidly. By the 1930s, music and programming was widely distributed to the public in the form of records. Also available, especially by the mid-1930s, were coin operated music machines, commonly referred to even today as jukeboxes. These machines were frequently placed in public places, like bars, resturants, and other gathering areas for maximum effect.13 The term jukebox refers to juke or “joot” joints, which were African American entertainment establishments concentrated in the rural South with drinking, music, and often gambling.14 Pay-by-the-play music machine industry representatives rigorously attempted to shed the name due to its associations with seediness and African Americans in segregated America but ultimately failed.15 Coin operated jukeboxes were big business, as it provided audio entertainment for cheaper than the cost of discs and a player, while creating new communal listening experiences in places otherwise quiet previously.16 Now, one could listen to new musical releases at the lunch counter, the train station, or even in place of local live musical entertainment at bars.17 The impact of jukeboxes was immense, with the recording industry taking notice and adapting its business model to accommodate the machines. New recordings were divided between slower, more intimate music for private listening through a record player at home and upbeat, danceable, or music otherwise suited for group listening made specifically with jukeboxes in mind.18 Jukeboxes often featured jazz, the blues, and swing music which would otherwise be harder to listen to on the radio and often made by African American performers.19 The jukebox was a quick commercial success in the U.S., with an estimated 400,000 of the units taking coins by 1940.20 Investors would make note of the commercial success of the jukebox when new audiovisual ideas would come to market.

Finally, televisions were a technological marvel for American consumers. Unlike the other forms of audiovisual technology mentioned though, televisions came later. It wasn’t until the late 1930s that televisions were beginning to be marketed to wider audiences with higher availability. A pivotal moment for the television was the 1939 World’s Fair when RCA and NBC held the first regular television programming with live coverage of the opening ceremonies of the fair broadcast to the locals in New York City - about 200 television sets at the time.21 Upon initial release, television sets were quite expensive and would not see large consumer adoption until well after the war. By 1950, American television set ownership was still low, with only nine percent of Americans owning a set. That number would rapidly spike to 90 percent by 1960.22 With television ownership so limited in the 1940s, audiovisual alternatives that were smaller and in different locations than films in movie theaters had a potential path to success.