Leaves of Grass, 1860/61

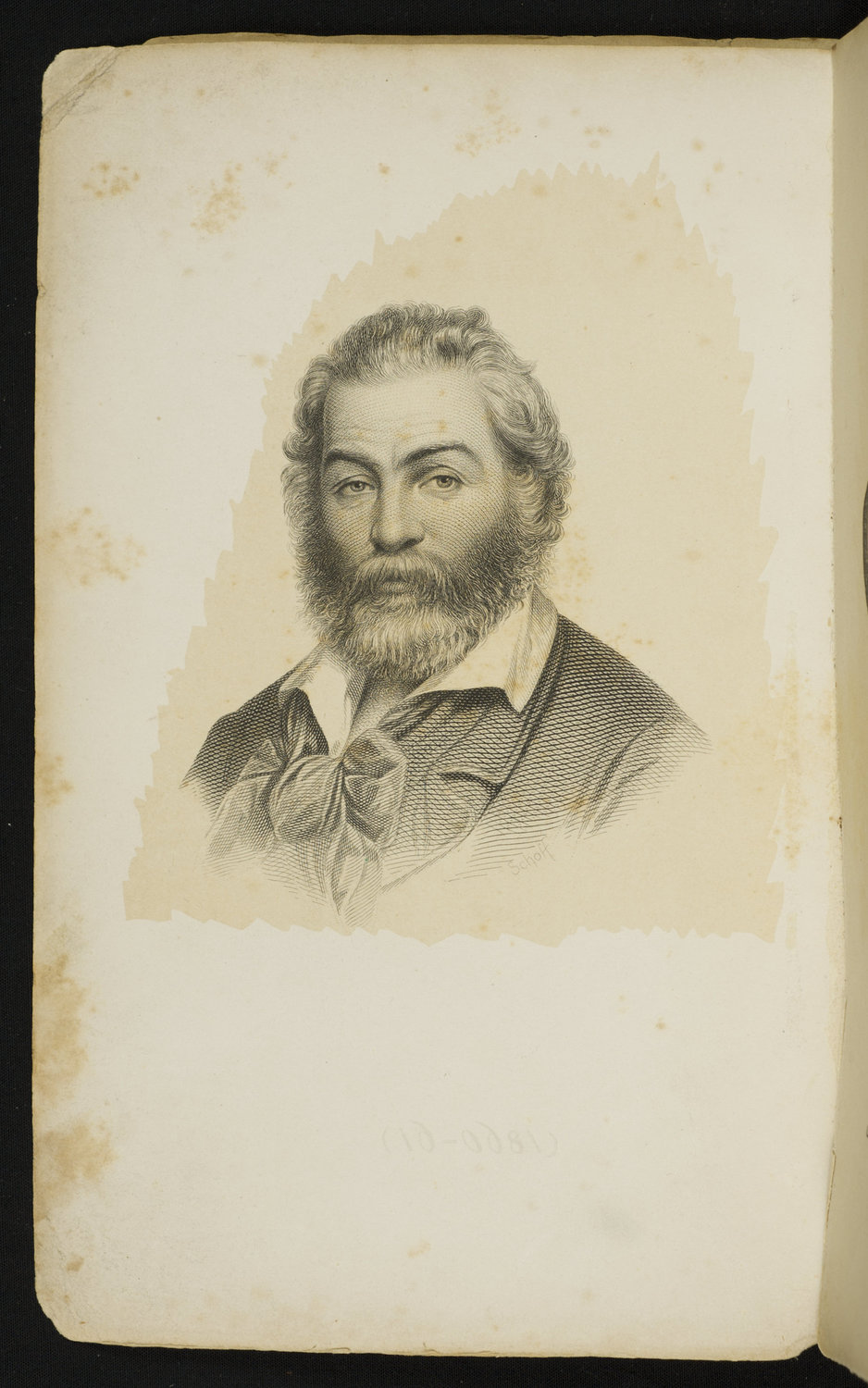

Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass. 3rd ed. Boston: Thayer and Eldridge, 1860/61. Frontispiece, after a design by Stephen Alonzo Schoff.

This is the third edition of Leaves of Grass, in a presumed first state of frontispiece, signed “Schoff” in plate on a light brown background (Myerson, p. 29), first printing, first American issue. Bound in unprinted wrappers.

The frontispiece engraving, made by Stephen Alonzo Schoff from an oil painting portrait by Charles Hine, shows a Byronic poet rather than a laborer, the greying hair combed back, the beard carefully groomed, the open collar tamed by a cravat (ill.1). Whitman later noted that "I was in full bloom then,” hale and hearty. Whitman added line drawings to the texts, among them the first instance of the butterfly rising from the poet’s hand, a metaphor for the uplifting of the reader’s spirit he hoped to accomplish.

Note Whitman’s deliberate addition after the publication date: “Year 85 of The States,” an exhortation to keep that history going, especially in the face of national dissolution. Although Whitman had simplified the cover design, he still experimented with fonts—note the thin loops attached to letters on the title page, which were meant to resemble human sperm, a continuation of the procreative energy emanating from the cover of the first edition. The author’s name continues to be absent from the title page. Despite the uplifiting illustrations, the book also conveyed a sense of impending crisis and personal as well as national crisis to its readers. The Lilly edition was once owned by Mary P. Winter of Gloucester, Mass. (and then passed on, as noted on the flyleaf, to her nephew Allan Winter Rowe, a professor at MIT).

Multiple passages are lightly marked with pencil, and many of them seem to center around death: “And I will show you that nothing more beautiful can happen than death” (p. 15); “I do not know what follows the death of my body,/ But I know well that whatever it is, it is best for me” (p. 229); or p. 266, where Whitman evokes “the beautiful touch of Death.”