Booth Tarkington

Born in 1869 in Indianapolis into a well-connected, privileged family, Newton Booth Tarkington, named after his uncle who was then governor of California, “Tark” (as fellow students called him) attended Purdue and Princeton. Though he never graduated, Princeton awarded him two honorary degrees. He is one of only three authors to have won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction twice, for The Magnificent Ambersons and Alice Adams. A social conservative, he served one term as a Republican in the Indiana House of Representatives; later, he would oppose FDR’s New Deal. While he lacked the subtlety of Henry James, Tarkington became one of the most effective and popular critics of the consequences of social change.

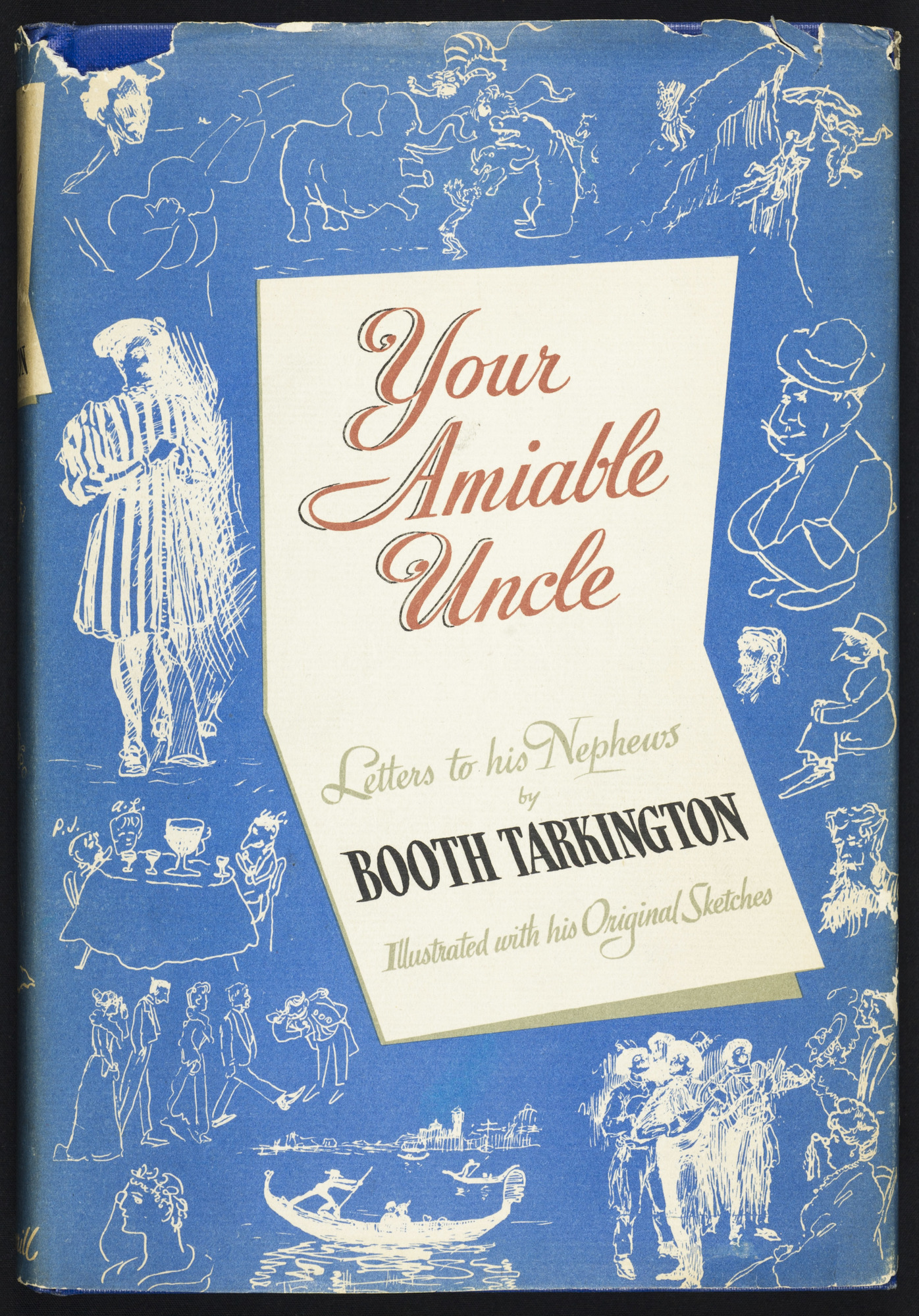

Booth Tarkington, Your Amiable Uncle: Letters to his Nephews by Booth Tarkington. Illustrated with his Original Sketches. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1949.

A collection of amusing letters sent in 1903/1904 to Tarkington’s nephews John, Donald, and Booth James during his first trip abroad with his parents and his wife. Herman B Wells’s copy, with his pencil marks next to a passage in which Tarkington, writing from Rome, calls Nero “a quiet person of domestic and simple manners, a good deal like Aunt Jennie Hendricks in his simple ways.”

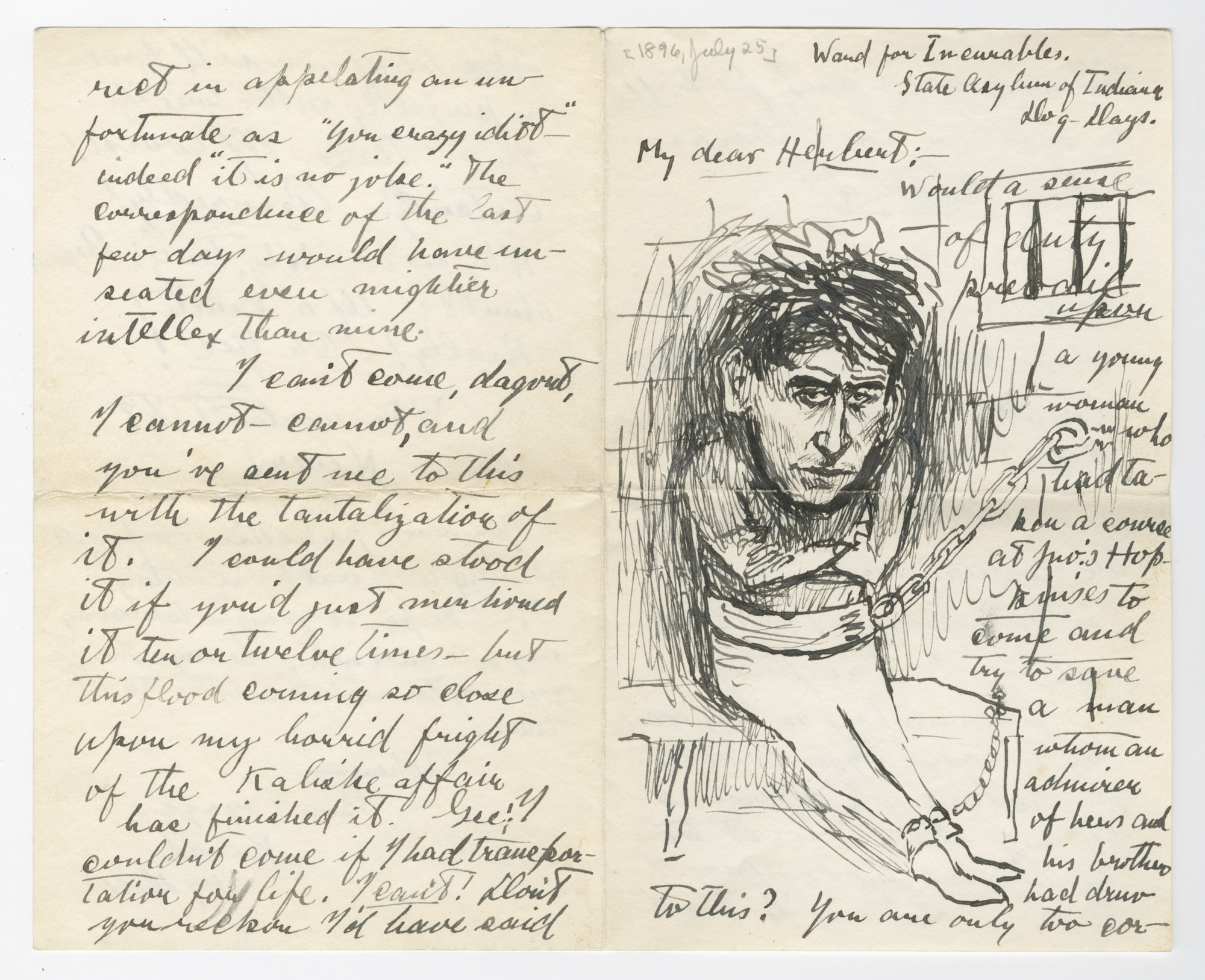

Booth Tarkington to Herbert Milton Rogers, [July 25, 1896].

Herbert Milton Rogers (1870?-1931) was a lawyer in Omaha, Nebraska and a former classmate of Tarkington at Princeton University. Providing a startling ink-portrait of himself in chains, Tarkington claims to be writing from the “Ward for Incurables. State Asylum of Indiana Dog-Days” in order to justify his not coming to visit Rogers. “The keeper is going to take away my pen and ink; he says I’m growing too violent to be trusted with it.”

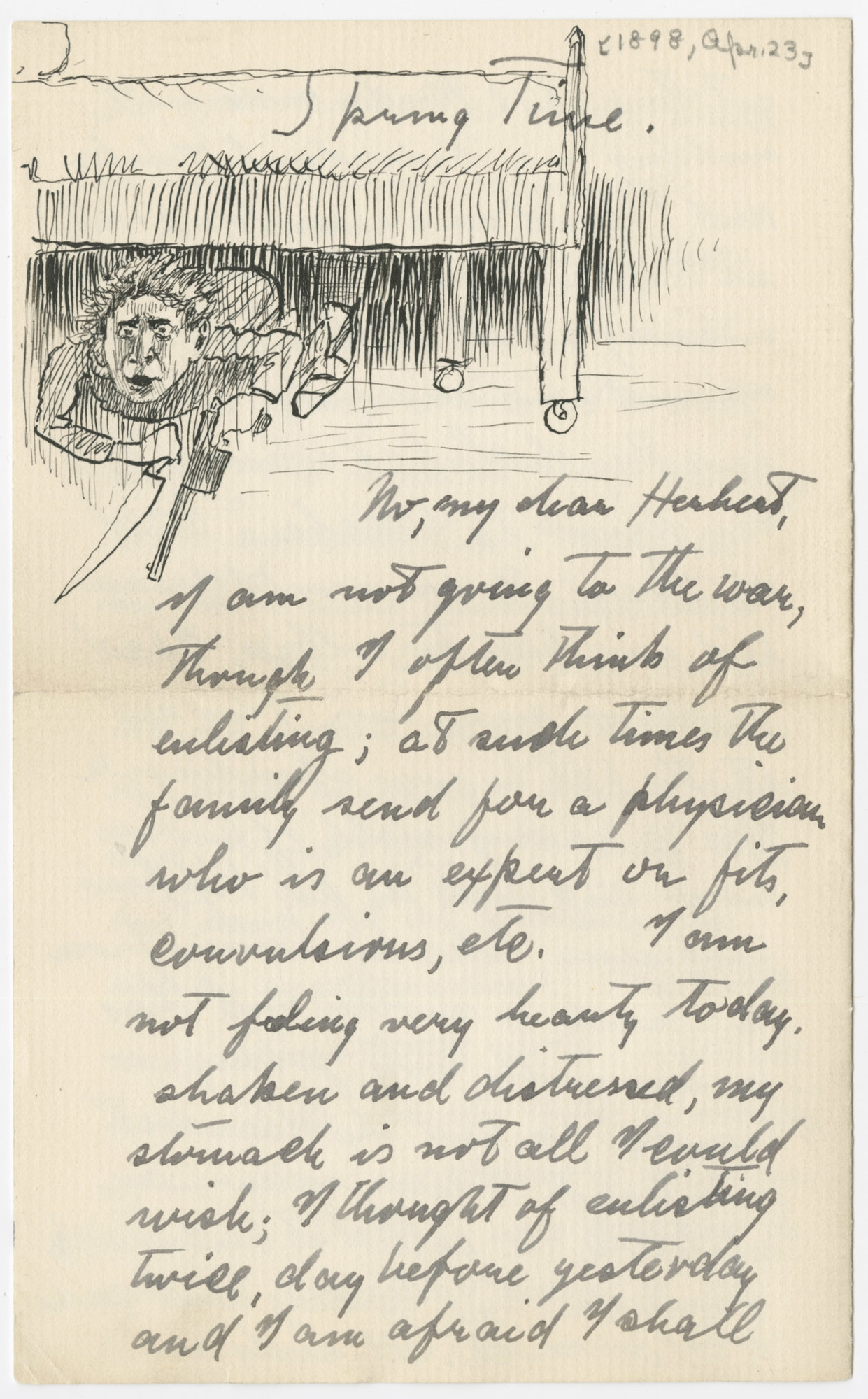

Booth Tarkington to Herbert Milton Rogers, April 3, 1898.

In this delightful letter to Rogers, Tarkington parodies his own conflicted feelings about the Spanish-American war, which make him sick to the stomach: “Every time I think of it the attack is worse and the treatments severer. The difference between this attack and others is that in ordinary sickness one gets into bed; but in this I get under it.” The drawing shows a distressed Tarkington under his bed. In the rest of the letter he announces his intention to visit Rogers in Omaha, “which is more interior than Indianapolis—and, I hope, less patriotic.”

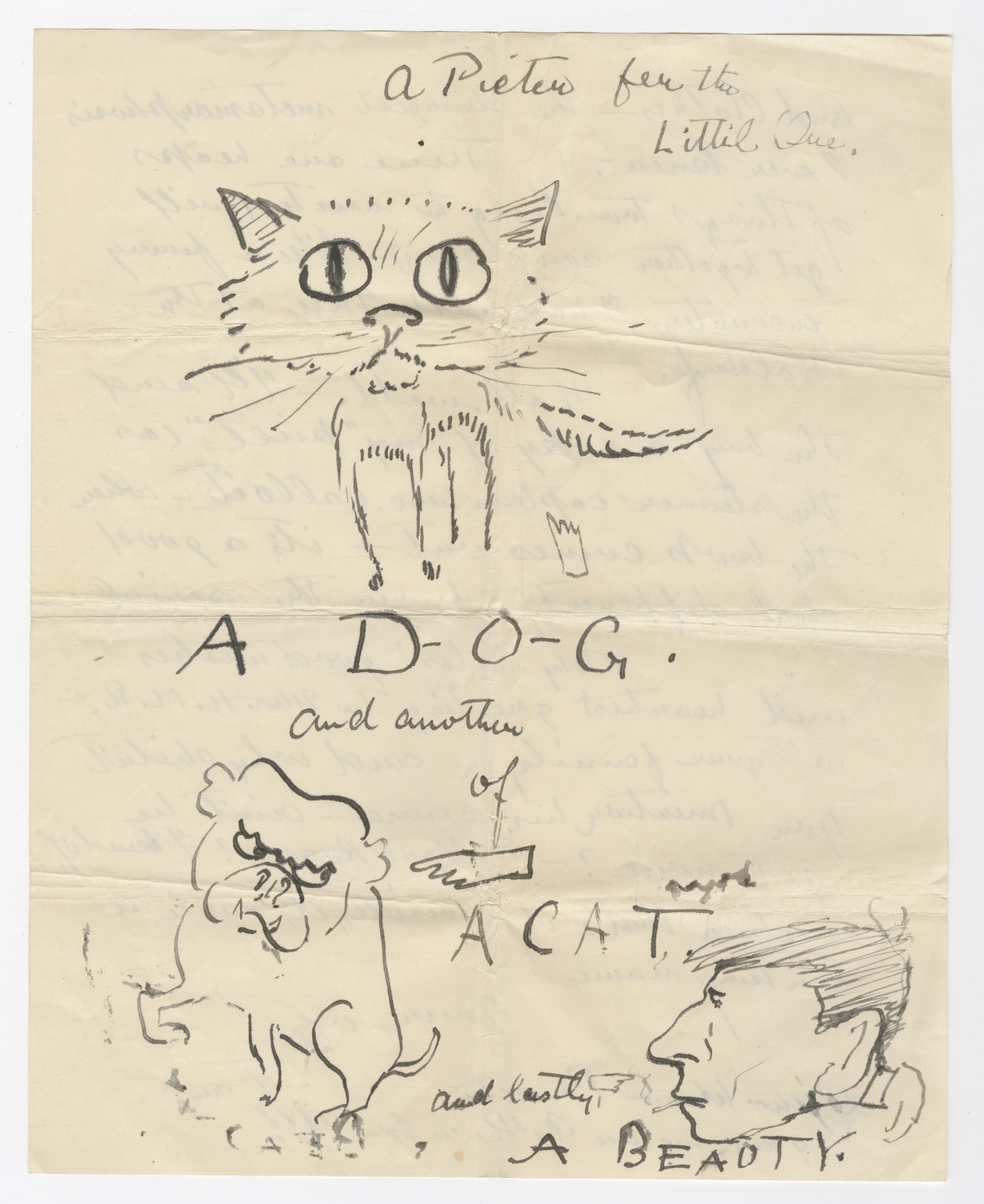

Booth Tarkington to Herbert Milton Rogers, August 31, 1899.

Sent from his sister’s cottage on lake Maxinkuckee, Indiana, upon the news of the birth of Rogers’s son. Tarkington provides an entertaining ink drawing for the “Little One,” intentionally confusing the captions, a first lesson for Rogers’s boy in the arbitrariness of the signifier.

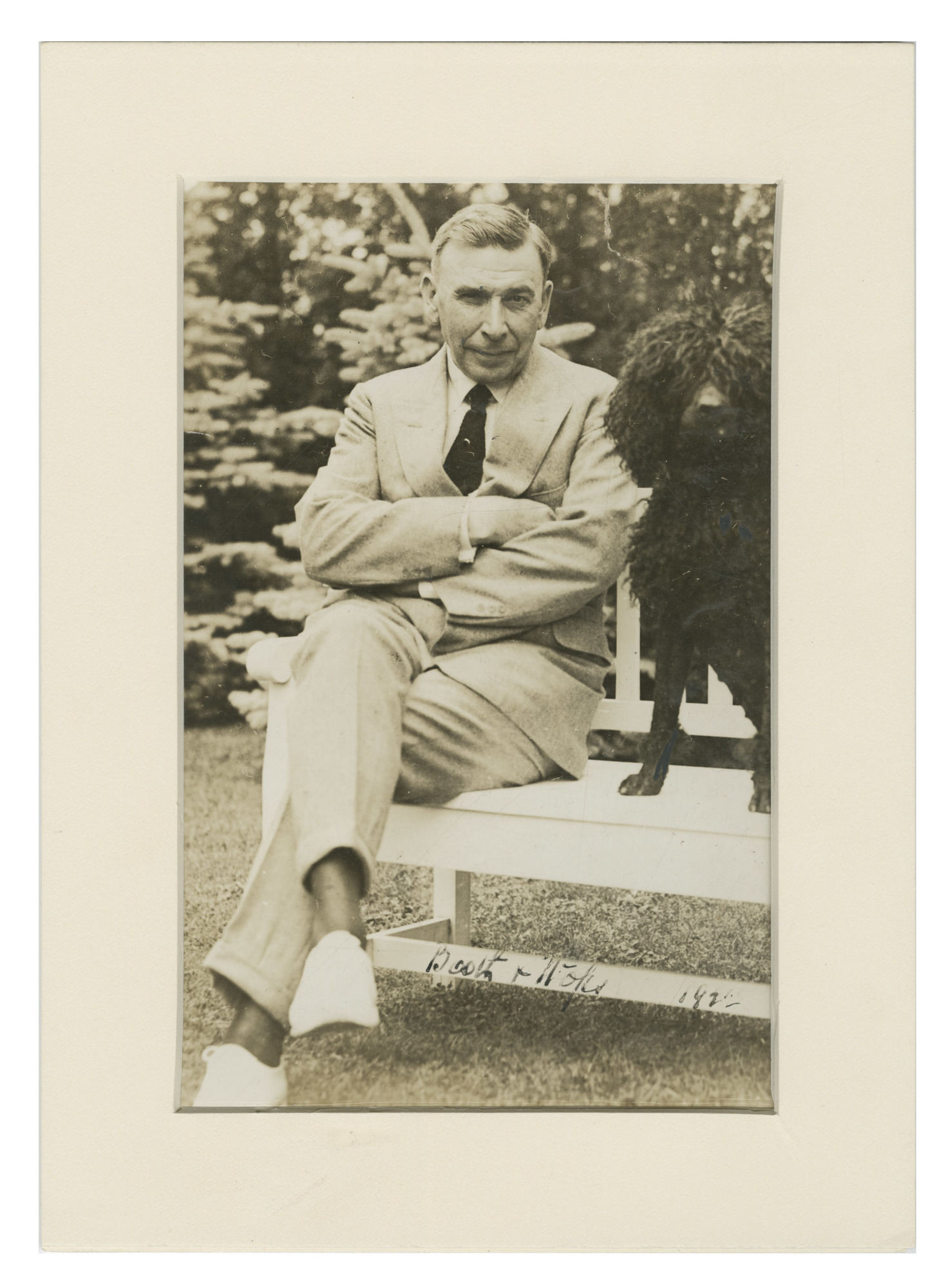

Unknown photographer, Booth Tarkington,1922.

In this photograph, taken in 1922, the writer poses with “Mops of beloved memory,” according to a holograph note on the verso. The location is identified as “Newburyport”—likely Newburyport, Mass., not too far away from Kennebunk.

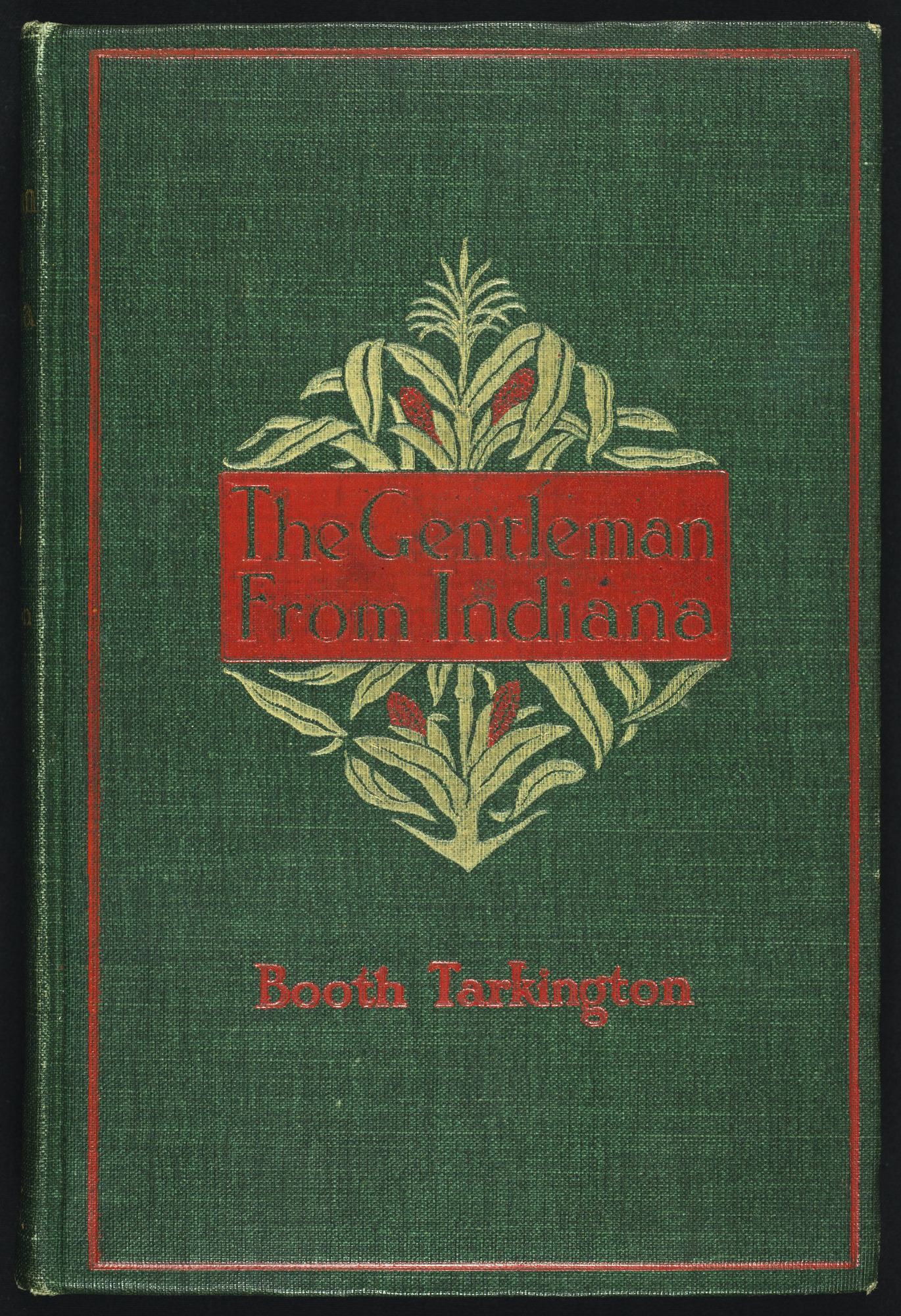

Booth Tarkington, The Gentleman from Indiana. New York: Doubleday & McClure, 1899.

The story of out-of-towner John Harkless, who takes over the newspaper in the fictional Plattville, Indiana, and turns it into a success, although he cannot divest himself of his sense failure before he truly accepts Plattville as a home. The novel, which was serialized first and then turned into a movie, has a confusing plot but brims with memorable lines, among them: “Congress is our greatest virtue, but congressmen are our greatest fault.” Author’s dedication copy inscribed to “To Miss Smith with the heartiest greetings from Author Booth Tarkington.”

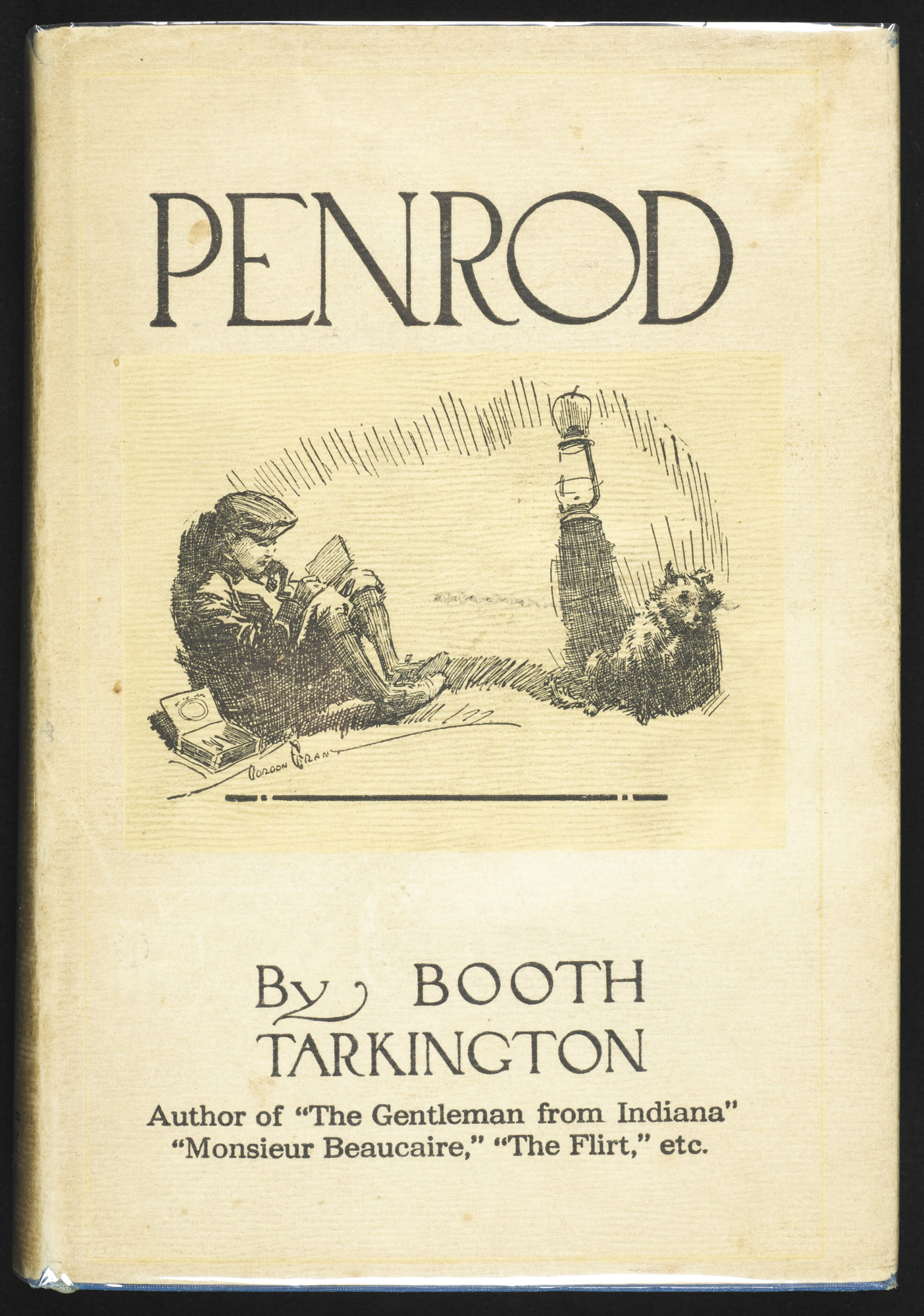

Booth Tarkington, Penrod. New York: Doubleday, Page, and Company, 1914.

A series of sketches featuring an eleven-year-old boy, Penrod Schofield, a Midwestern version of Tom Sawyer, that proved to be so popular with readers that “Tark” provided two sequels, Penrod and Sam (1916) and Penrod Jashber (1929). The boy’s misadventures—which involve such capers as stuffing a girl’s braid into an inkwell or gorging oneself on watermelons—seem painfully tame even by Twainian standards of badness. Dedicated by “Bud” (Tarkington’s nickname) to his mother. Illustrated by Gordon Grant.

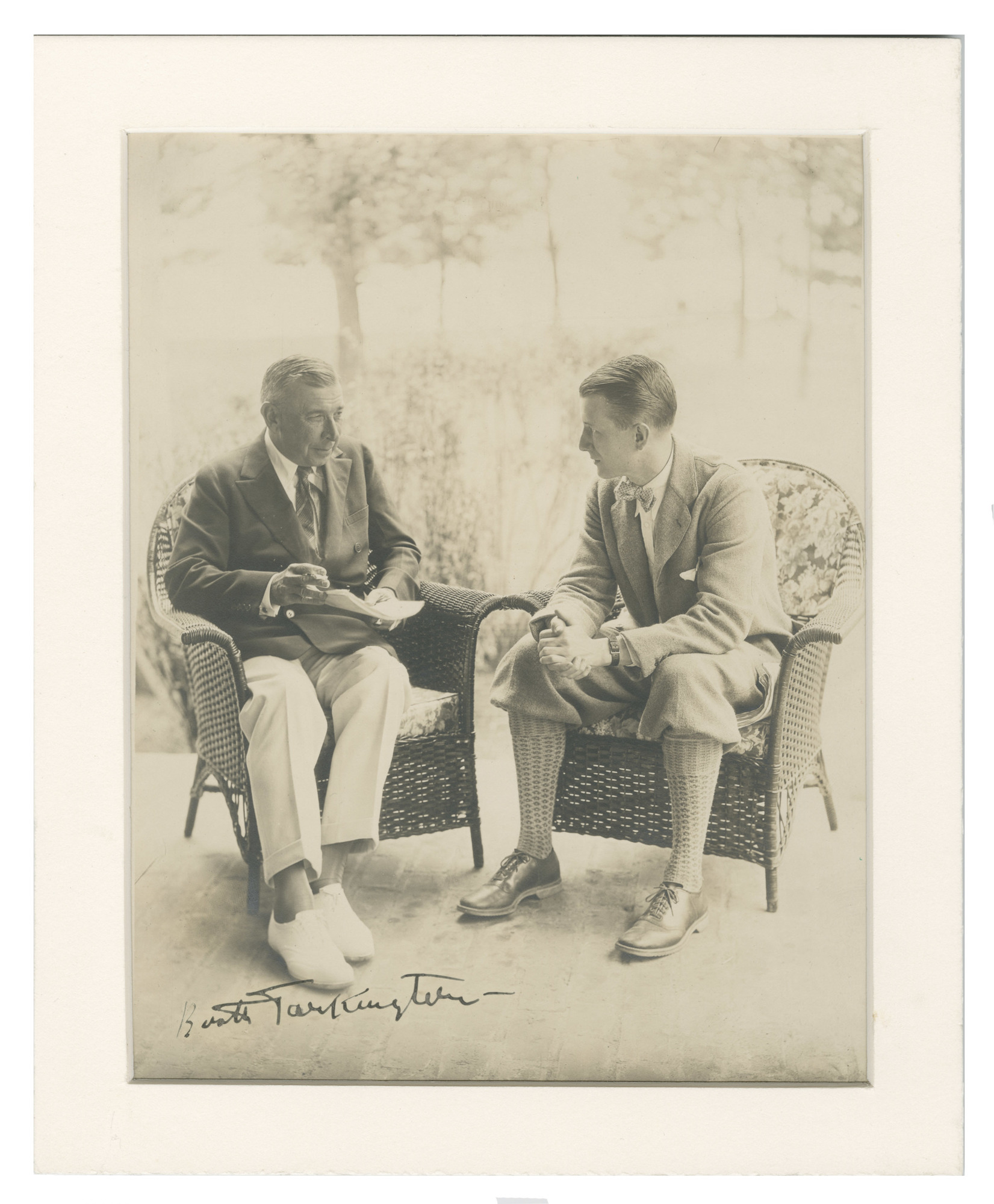

Unknown photographer, Booth Tarkington with Elliott Nugent, ca. 1927.

According to inscription, taken at the Lakewood Theater in Skowhegan, Maine, one of the oldest summer theatres in the U.S. According to the Lewiston Daily Sun, July 8, 1927, the actor and director Nugent (1896-1980) had been cast in Tarkington’s play Hoosiers Abroad, an adaptation of Tarkington’s play The Man from Home. Notes the Daily Sun: “Mr. Tarkington … will be at Lakewood during the week of the play’s production to supervise the final preparation of the play for Broadway. The plot and the story have been altered considerably but it still retains the charm and humor that made it one of the outstanding pieces of dramatic writing the American theatre has ever known.”

Newton Booth Tarkington: His Golden Book, 1930-1931.

A collection of tributes presented to Tarkington collected for the Christmas season, with signatories ranging from President Hoover to Charlie Chaplin. Noteworthy are the contributions of activist and social worker Jane Addams of Hull House (“To Booth Tarkington with gratitude for the illumination he has cast upon many of life’s perplexities”) and Harvey Firestone, the tire king (“I know of no person in the world wo has given more people more pleasure than you have—and I count myself as one of those people”).

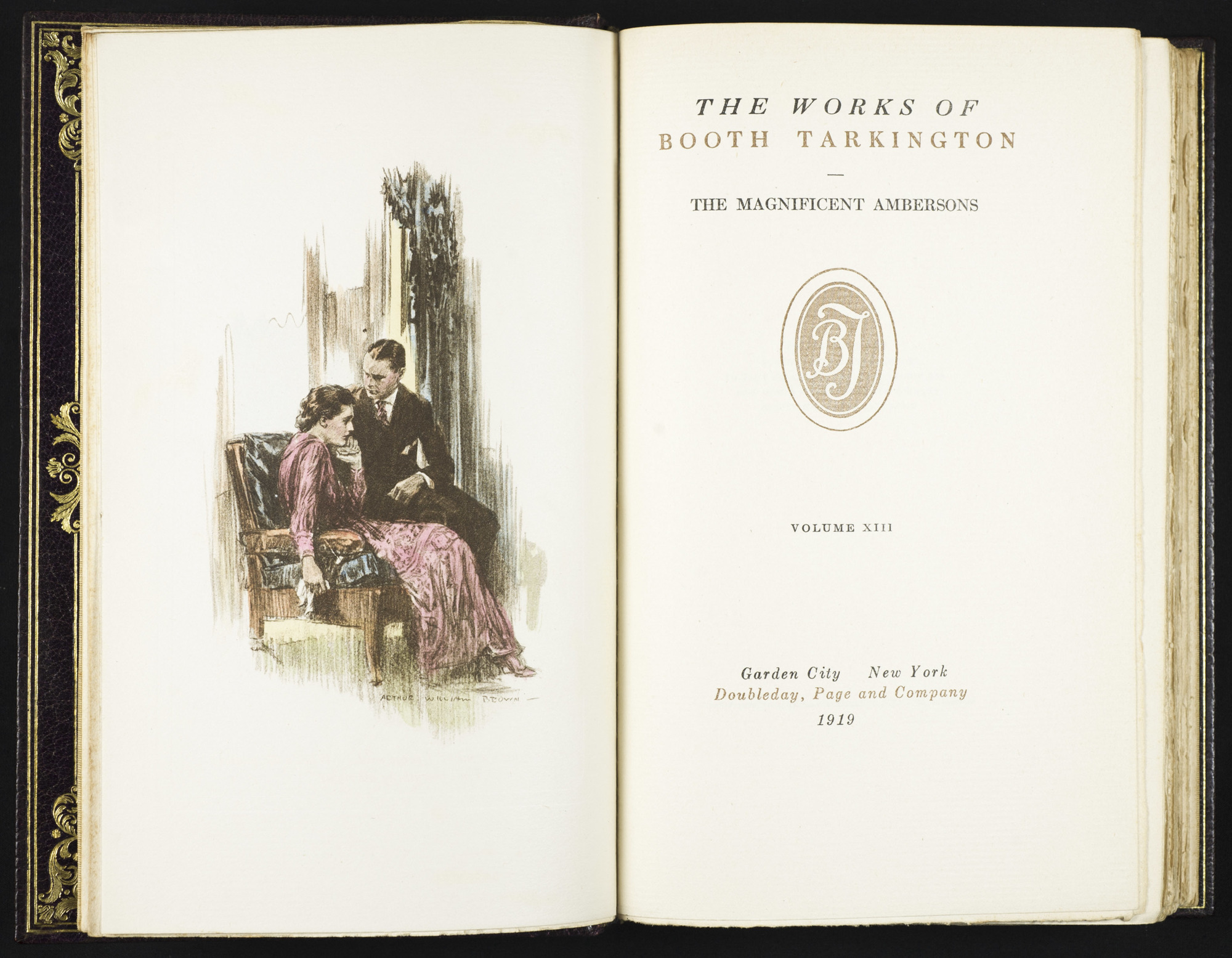

Booth Tarkington. The Magnificent Ambersons. Autograph edition, vol. XIII. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1919.

Tarkington’s most famous book, thanks to Orson Welles’s 1942 film adaptation. In the unbearably mediocre George Amberson Minafer the author portrays the decline of a wealthy family’s magnificence, which he parallels with the rise of the automobile. Illustrated by Arthur William Brown.

Booth Tarkington, The World Does Move. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1928.

Autobiographical volume covering the years 1900-1928. The main theme is change: the transition from gaslight to electrical light, which wrecked the old theatre trick involving people blown up by gas; the rise of the New Woman; the exaggerated importance of sexuality in art. In the end, change is inevitable, but it should not come at the risk of discarding the past entirely: “every new age has at its disposal everything that was fine in all past ages, and its greatness depends upon how well it recognizes and preserves and brings to the aid of its own enlightenment whatever worthy and true things the dead have left on earth behind them.”

Booth Tarkington, “To the Girls and Boys of Indianapolis,” broadside, 1945.

Exploiting his fame and moral authority, Booth Tarkington appeals to the children of Indianapolis to raise money for the war effort.

Unknown photographer, Booth Tarkington in Old Age, undated.

Likely taken at his summer estate in Kennebunk, Maine. In the late 1920s, Tarkington began his long battle with failing eyesight. He regained partial vision only after subjecting himself to a dozen eye operations but depended on a secretary to continue his writing.