Hoosier Women Writers

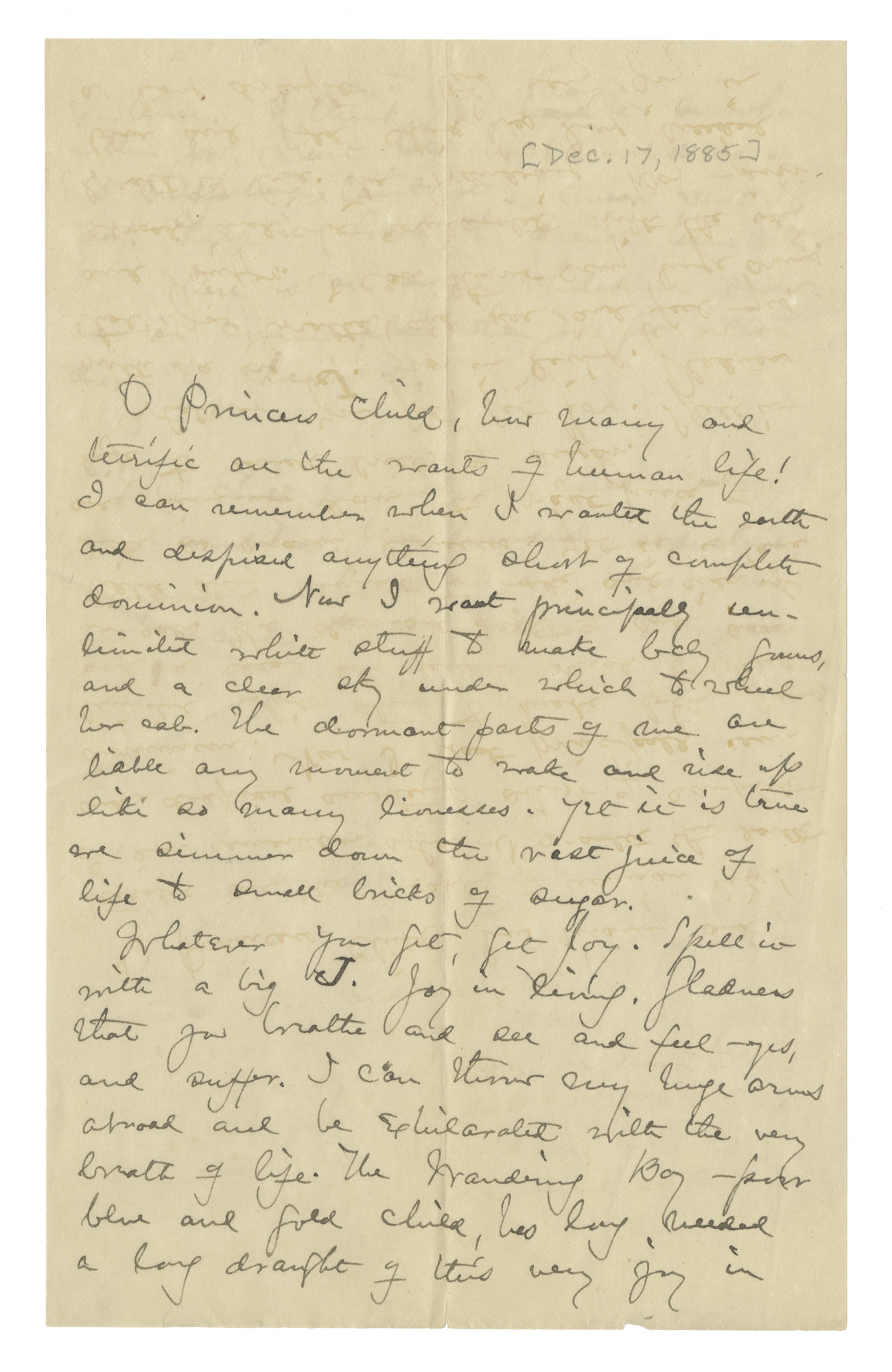

Mary Hartwell Catherwood to Mary Riley, Care of Bradstreet’s Agency, December 17, 1885.

Mary Hartwell Catherwood was born in Luray, Ohio in 1847 and grew up in Illinois. In 1877, she and her husband James Catherwood moved to Oakford, Indiana, and then to Indianapolis, where she struck up an intense friendship with James Whitcomb Riley’s youngest sister, Mary (1864-1936). The author of historical romances, Catherwood found it difficult to restrain herself in her letters: “O Princess Child, how many and terrific are the wants of human life!” she begins this letter to Mary and then adds ominously, “The dormant parts of me are liable any moment to wake up and rise like so many lionesses.” Catherwood’s advice to Mary sounds as if it had been inspired by Whitman: “Whatever you get, get joy. Spell it with a big J. Joy in living, gladness that you breathe and see and feel—yes, and suffer. I can throw my huge arms around you and be exhilarated with the very breath of life.” Mary Riley later married Frank L. Payne, a newspaperman; by 1900, she had left her husband. Perhaps she had expected the same intensity Catherwood had shown towards her….

Unknown photographer, photograph of Mary Hartwell Catherwood, undated.

Signed by Catherwood as “Votre Maman.” The source of the quotation she adds, “For precious is the love of love. / Grief has inherited—,” remains obscure. Was it intended as a veiled comment on her unfulfilled yearning for Mary?

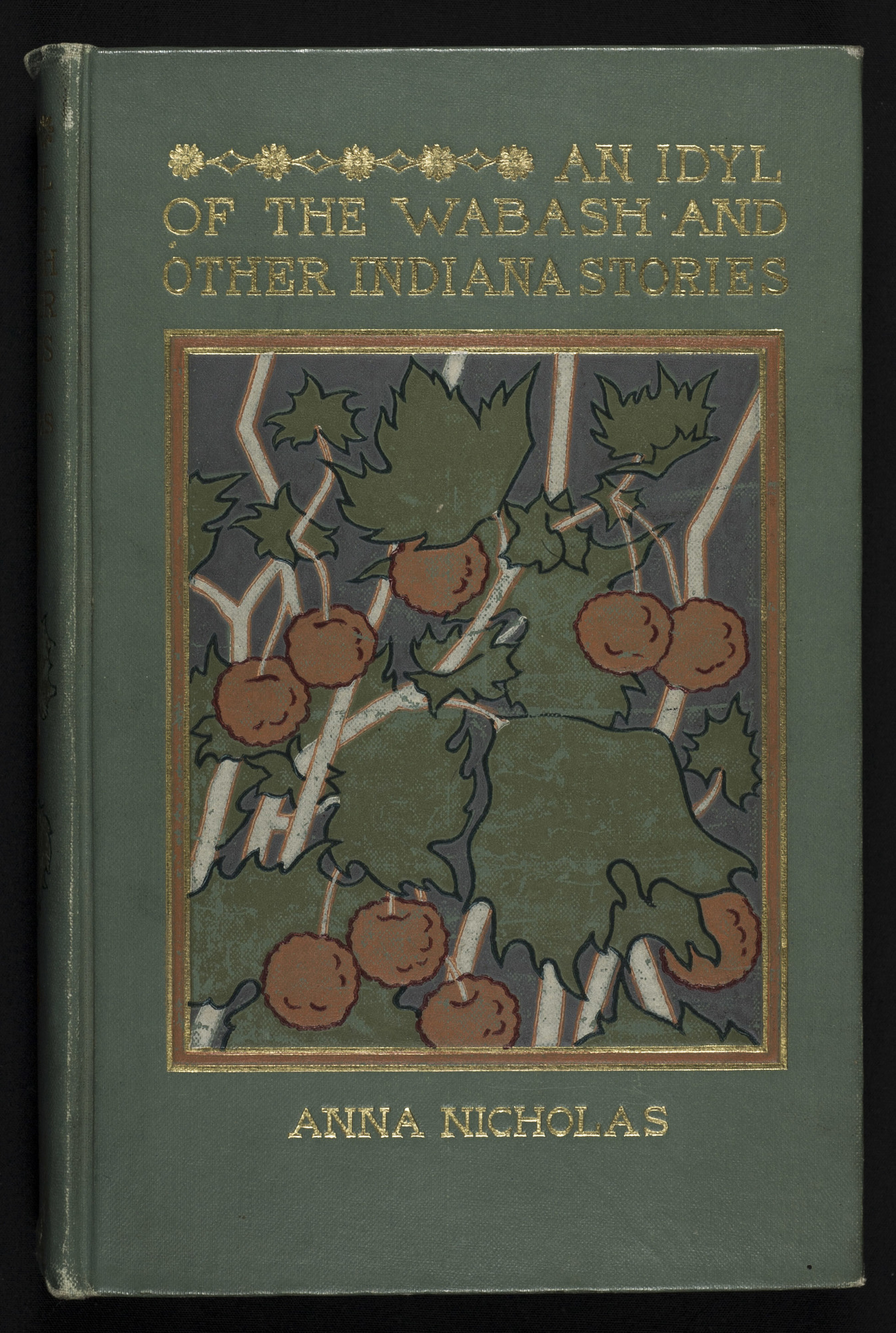

Anna Nicholas, An Idyl of the Wabash and Other Stories. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1899.

Born in Meadville, Pennsylvania, Nicholas (1849-1929) spent most of her life working for the Indianapolis Journal (later the Indianapolis Star). Her sense of humor was no doubt sharpened by her efforts to be successful in a world dominated by men. When she was asked in a 1917 interview about the “joys of journalism,” she responded, “They do not at once suggest themselves.” Nicholas could also be withering about the poems that were submitted to the Journal. About one particularly bad example, containing the lines “I wandered out one lovely night / Barefooted were my feet,” she remarked, “One can only hope it was a summer night.” The cover design for Idyl of the Wabash, her best-known book, as supplied by Evaleen Stein, an artist and poet from Lafayette, Indiana. This copy was formerly owned by George Cottman, founder of the Indiana Magazine of History, whose critical comments and question marks can be found in the margins, notably next to the somewhat feminist observation Nicholas offered about one of her characters: “She was one of those timid, clinging creatures such as all women are exhorted to become.”

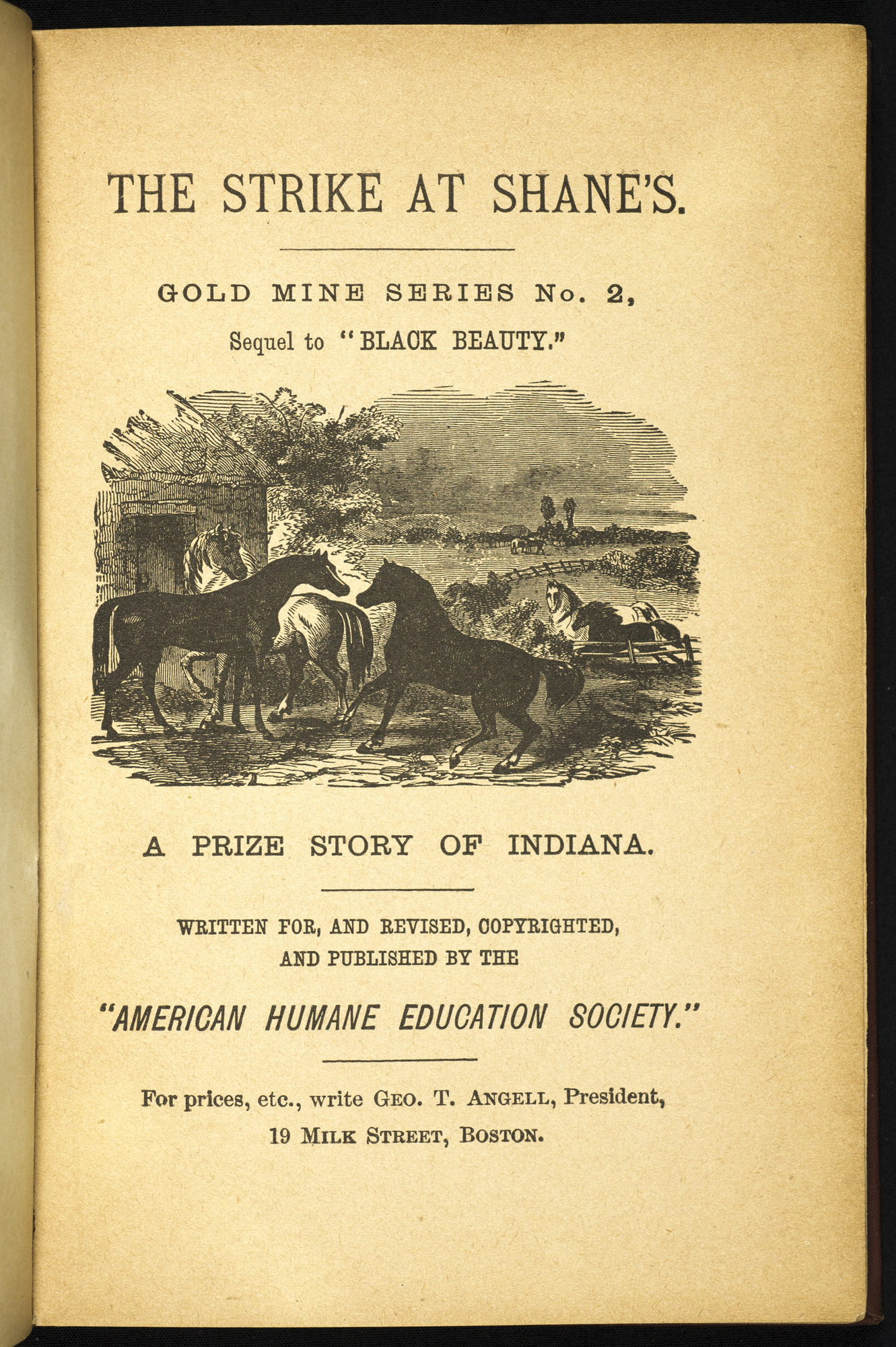

[Gene Stratton-Porter], The Strike at Shane’s: A Prize Story of Indiana. Gold Mine Series, No. 2: A Sequel to “Black Beauty.” Written for, and Revised, Copyrighted and Published by the American Humane Education Society, 1893.

This anonymous novel, now generally ascribed to Hoosier naturalist and novelist Gene Stratton-Porter (1863-1924), won a contest sponsored by the American Humane Education Society in 1893. Billed as a sequel to Anna Sewell’s popular novel Black Beauty and in uncanny anticipation of Orwell’s Animal Farm, it describes how the Farmer Shane’s animals, tired of years of abuse, go on strike. They are joined by the birds who, instead of pulling out the worms that affect Shane’s corn, put them back in. Naturally, the less acceptable animals—a hawk that wants to participate in the strike by killing off the farmer’s chickens and a rat that just hopes to profit from the cat’s inactivity—are excluded from this new impromptu barnyard alliance. The turning point comes when Farmer Shane’s cart is overturned by his uncooperative horse and his daughter notices—in a section that seems to predict Rachel Carson—that the birds have grown silent. Abusive farmer Shane realizes that love and a little help from the neighbors are the key to successful farming. Now he knows that he needs to be “kind towards all creatures that God has given us.”

Gene Stratton-Porter, The Song of the Cardinal: A Love Story. The Illustrations Being Camera Studies from Life by the Author. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1903.

The first book Stratton-Porter published under her own name is devoted to the courtship and subsequent “marriage” of a plucky young cardinal from the Limberlost Swamp, whose zest for life inspires Farmer Abram and his wife to put up “No Hunting” signs on their property: “people ort to act with some sense, an’ leave ’em ’lone.” The farmer angrily explains his ecological views to a young hunter he catches, despite the signs, on his property: “Sky over her head, airth under foot, trees round you, an’ river there,—all full o’ life that you hain’t no mortal right to tech.” Impressed with his new-found rhetorical prowess, Abram compares God to a painter who puts the best of himself in the picture, “an’ then hev’ some feller like you come ’long an’ pour turpentine on it jest to see the paint run.” However, the main attraction of the book lies not in the moralizing passages but in the chapters devoted to the mating rituals of the cardinals, written with great precision and sympathy. The book is accompanied by Stratton-Porter’s own photographs of the cardinals and their environment.

Gene Stratton-Porter, Moths of the Limberlost: With Water Color and Photographic Illustrations from Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1912.

Describing her book as “one of those works” that contribute to both literature and science, Stratton-Porter begins her investigation with a flowery tribute to the Limberlost Swamp: “To me the Limberlost is a name with which to conjure, a spot wherein to revel…. When I arrived, there were miles of unbroken forest, lakes provided with boats for navigation, streams of running water, the roads around the edges corduroy, made by felling and sinking large trees in the muck.” Stratton-Porters’ book is accompanied by her own watercolors and photographs of moths.

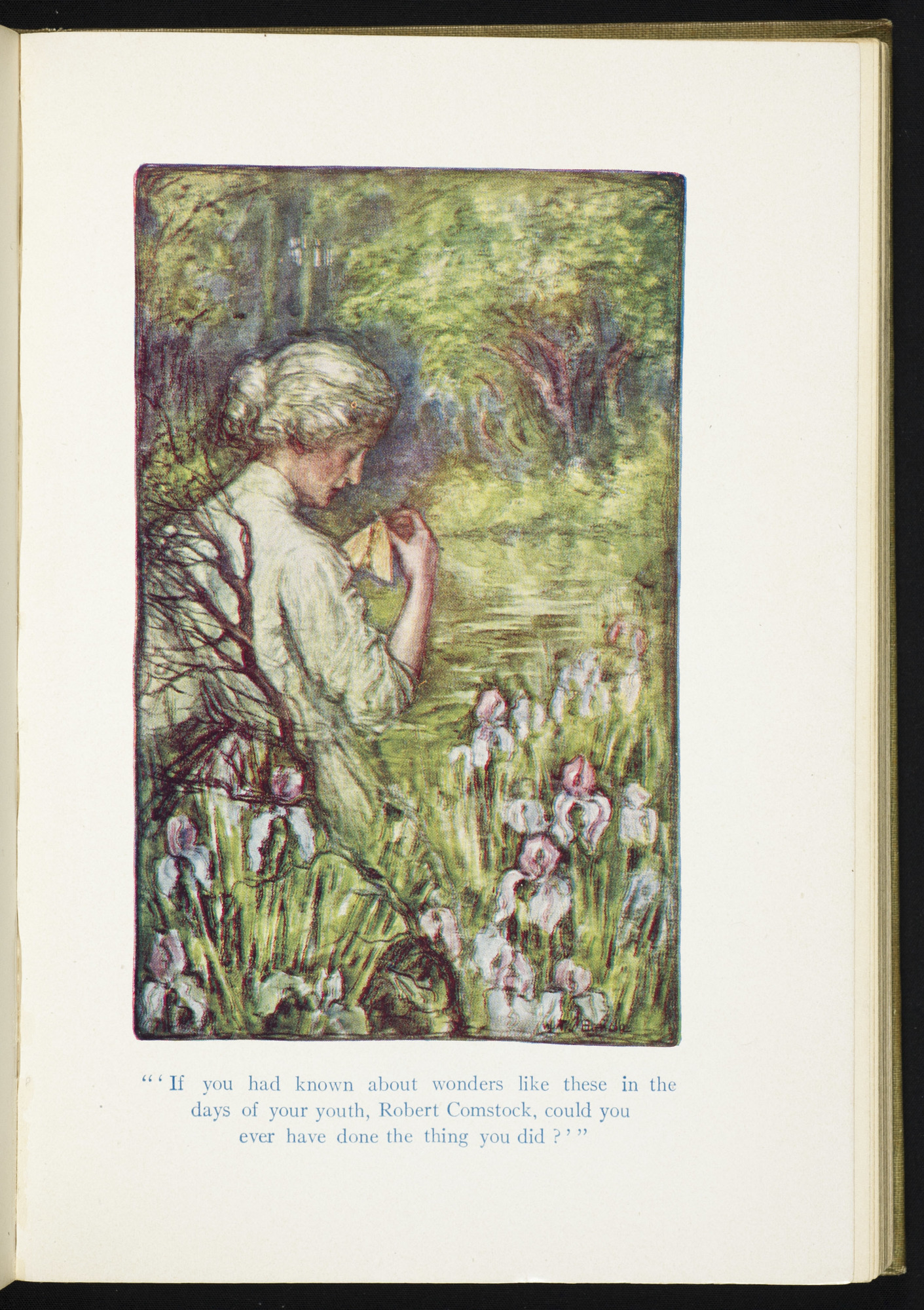

Gene Stratton-Porter, A Girl of the Limberlost. Illustrations by Wladyslaw T. Benda. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909.

Set in the Limberlost Swamp, the novel tells the story of Elnora Comstock who possesses “a large sense of brotherhood for all human and animate creatures.” She can hear the trees talk and, like her creator, has a deep affinity for the moths she gathers (she keeps only a tenth of them and sells them). Trained in the “School of the Woods,” she regains not only the love of her widowed, bitter mother but also a position as lecturer in natural history in the public schools of nearby Onabasha, Indiana and finally catches her biggest prize, the lawyer and nature enthusiast Phil Ammon from Chicago. Elnora witnesses first-hand how the landscape changes with every piece of wood claimed by humans: “The trees fell wherever corn would grow.” The exquisite drawings by the much sought-after Polish-American artist and maker of masks, Wladyslaw Benda (1873-1948), emphasize Elnora’s deep connection with the natural world around her, one that she is also able to impart to her normally stern mother Kate, as demonstrated in this illustration where Kate has just caught a prize moth. The caption for the illustration refers to the death of Elnora’s father, who perished in the swamp after cheating on Kate.

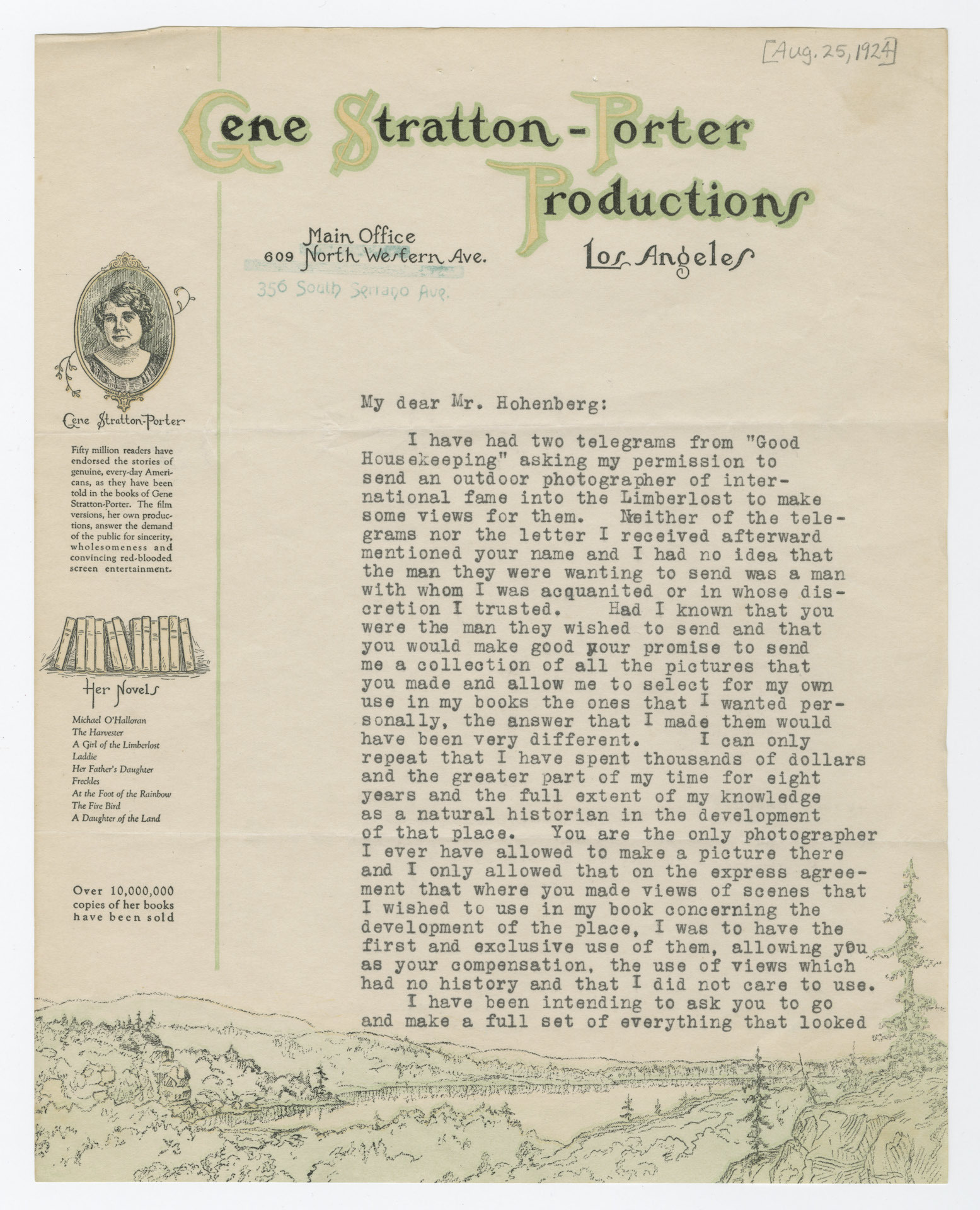

Gene Stratton-Porter to Frank Hohenberger, August 25, 1924.

Frank Hohenberger (1876-1963), owner of a small photography business in Nashville, Indiana, left his large collection of photographs of scenes in Brown County as well as other parts of Indiana and the world to Indiana University. Hohenberger was Gene Stratton-Porter’s preferred photographer, as is evident from this letter, written to him after Stratton-Porter had moved to Hollywood to launch her own movie company. Using her new company’s letterhead, Stratton-Porter instructs Hohenberger regarding the pictures of the Limberlost she wants him to take. “I have spent thousands of dollars and the greater part of my time for eight years and the full extent of my knowledge as natural historian in the development of that place.” A few months later, on December 6, 1924, Stratton-Porter, arguably Indiana’s most widely-read female author, died from injuries sustained in a traffic accident.

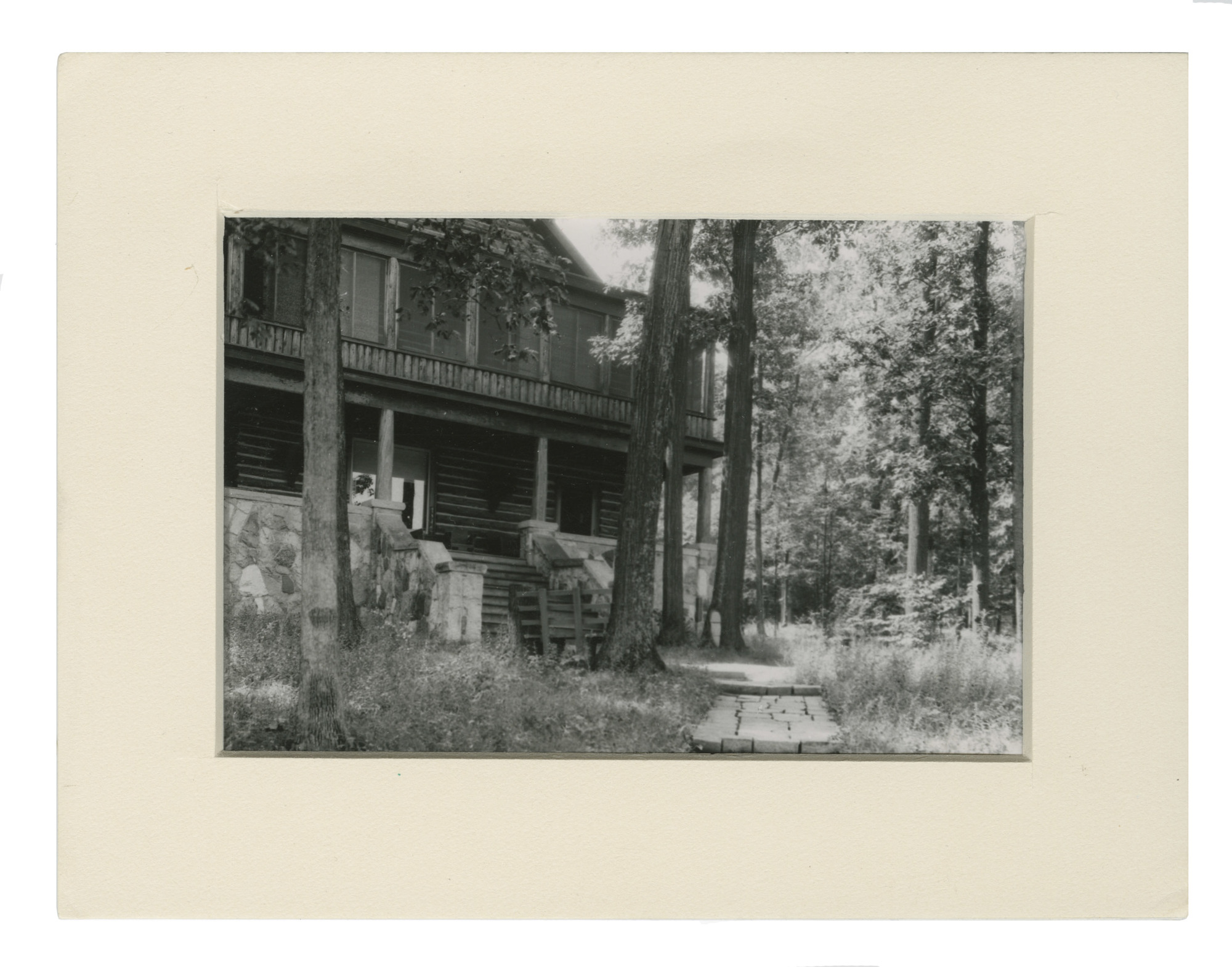

Frank Hohenberger, photographer, Limberlost Cabin and “Limberlost Cabin” near Rome City, Indiana, Lake Sylvan, ca. 1924.

From negatives in the Frank Hohenberger Collection.

Maie Clements Perley, Without My Gloves. Philadelphia: Dorrance and Company, 1940.

An amusing memoir by the British-born wife of Rabbi Martin Perley, who was appointed Director of the Indiana University Hillel Foundation in 1938. A social conservative who defends segregation as something that keeps the blacks in safe spaces, Maie Clements Perley casts a withering look at the looseness of manners in Bloomington or “Doomington,” as she prefers to call it. Shown here is a funny passage about the “disheveled” appearance of male students, whom she finds “slovenly in the extreme.” On the IU campus, open shirts are, she determines, the rule rather than the exception. Mr. and Mrs. Perley did not stay; by 1941, they had cleared out of Doomington.

Maie Clements Perley, Typescript of Without My Gloves, carbon copy in binder, 1940.

Apparently the draft of Perley’s manuscript sent out by her literary agency. Pearn, Pollinger & Higham was an established firm based in London, whose clients included the likes of Graham Greene. As David Higham Associates the agency continues to exist today, representing literary luminaries such as Stephen Fry and J. M. Coetzee. The typescript shows some evidence of light revision as well as what must have been the original title, “I Find America.”