James Whitcomb Riley

Born in Greenfield in 1849 as the son of an attorney, Riley was an undistinguished student. After unsatisfactory beginnings as an itinerant sign painter and local journalist, he became, by dint of hard work and an uncanny sense of audience expectations, one of the most recognizable names in the pantheon of Hoosier writers and one of the best-loved poets in the United States, the favorite writer of actor James Dean. A lifelong bachelor, Riley spent the last three decades of his life in a rented home on Lockerbie Street in Indianapolis, where his regular visitors included scores of Indiana schoolchildren and celebrities such as the perennial Socialist presidential candidate and labor organizer Eugene Debs. What was not so obvious to his fans were Riley’s internal struggles: his alcoholism, his loneliness, and a lingering sense that his considerable talent had destined him for more than the role of the benign “Hoosier poet.” Upon his death on July 22, 1916, more than 35,000 people filed past his casket as it lay in state under the dome at the Indiana State Capitol. Celebrated in his lifetime as a dialect poet who successfully dispelled the image of Hoosiers as backward people not worthy of literary treatment, Riley has more recently been recognized as a remarkably modern in the way he managed his poetic reputation.

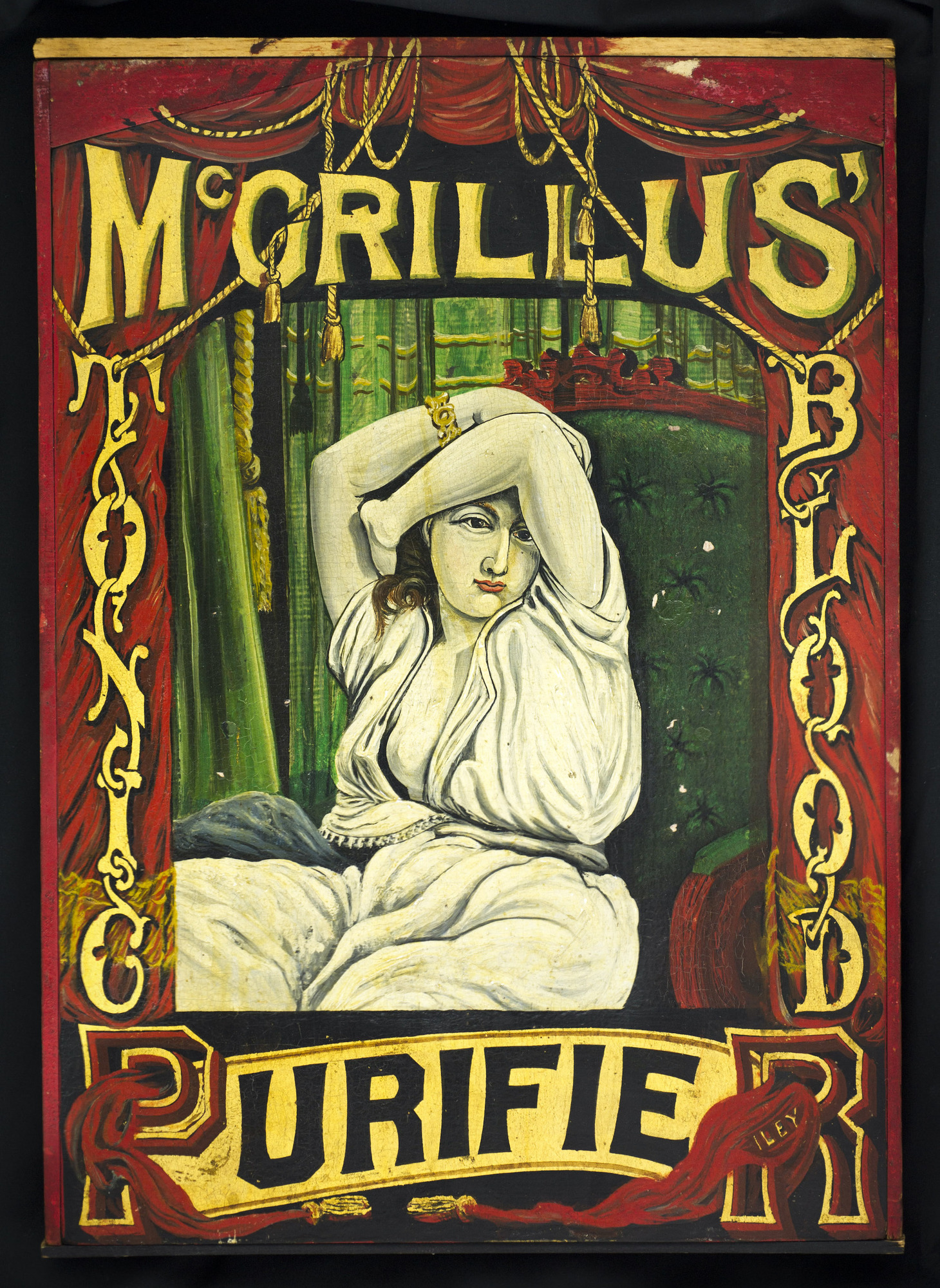

James Whitcomb Riley, Sign for McCrillus’ Tonic Blood Purifier. Oil on wood, 1872.

In 1871, Riley trained with a painter in Greenfield, a skill that came to full fruition when he joined an itinerant salesman of patent medicines, “Dr” McCrillus, whose “Popular Standard Medicine Show” arrived in Greenfield in 1872. But Riley’s involvement was not limited to painting; he also provided musical and other kinds of entertainment in between McCrillus’ sales pitches. That usually involved playing the banjo or belting out verse written for the occasion, but in one particularly egregious instance that has been reported, he posed as a formerly blind painter who had his eyesight restored by McCrillus’ blood purifier. It is not clear if the somewhat lasciviously posed, dangerously pale lady featured here is shown in a state before or after the consumption of McCrillus’s curative tonic.

Wayman Elbridge Adams, James Whitcomb Riley, with dog Lockerbie. Oil on canvas, undated.

Born in Muncie, Indiana, in 1883, Adams trained at the Herron School of Arts in Indianapolis but spent most of his career working in New York City and California. Nicknamed “Lightning” for the speed with which he would complete a portrait in one sitting, Adams died in Austin, Texas, in 1959.

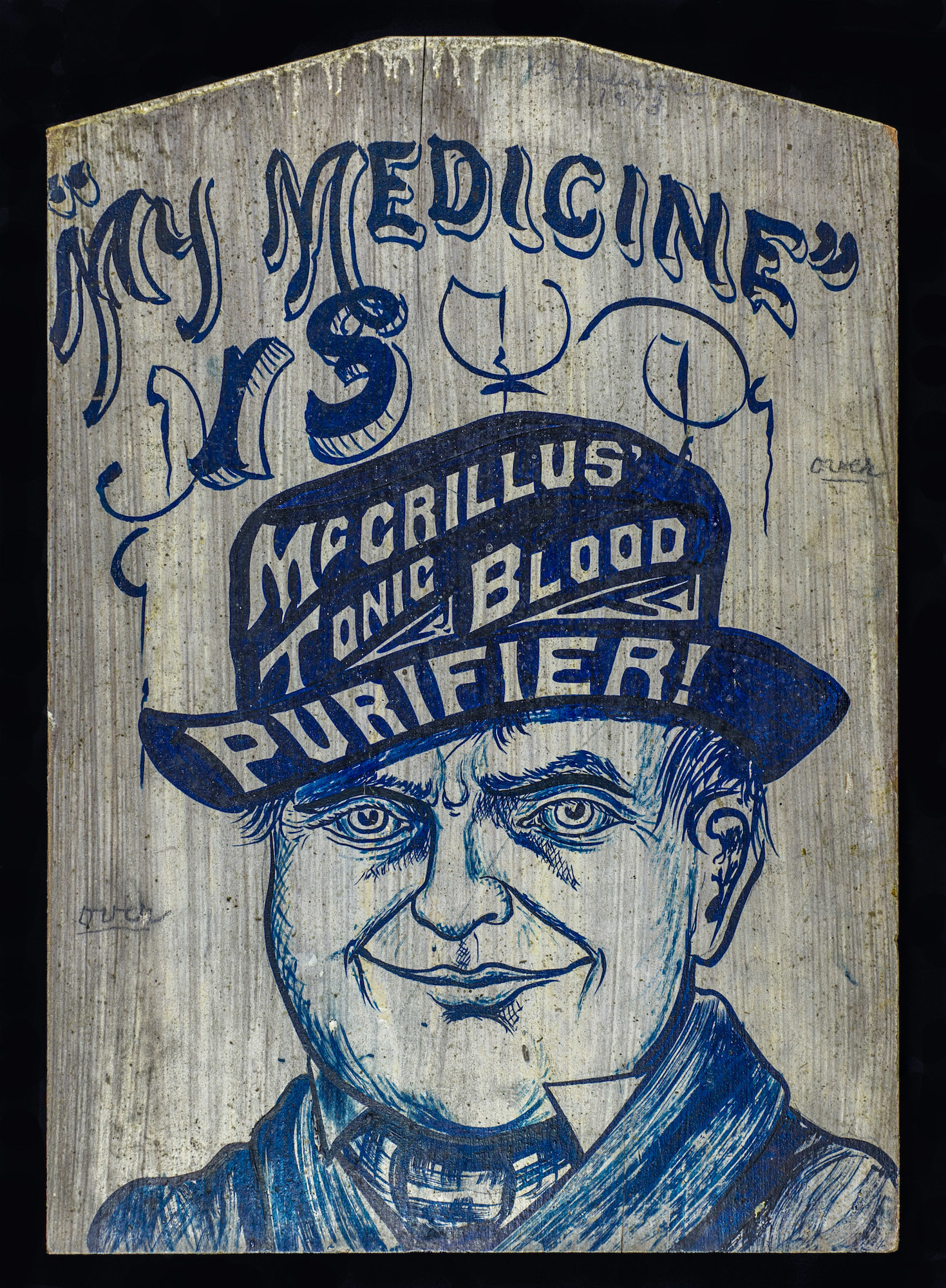

My Medicine Is McCrillus’ Tonic Blood Purifier. Oil on wood, 1872.

Working for McCrillus was a second sign painter, James McClanahan. Combining forces, Riley and McClanahan left the medicine show in the spring of 1873 and formed “The Riley & McClanahan Advertising Company,” which specialized in painting advertising slogans on Hoosier barns. The company quickly expanded to four painters and the name was changed to “The Graphics.”

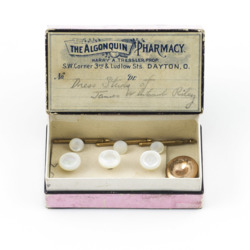

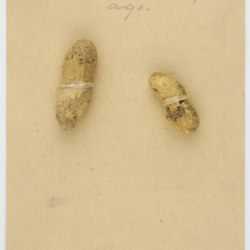

James Whitcomb Riley paraphernalia

In 1878, Riley started performing his poetry in public, commanding large crowds wherever he appeared, though these events were increasingly complicated by his need to fortify himself with drink before he went on stage. The two peanuts shown here were used by Riley in performances of his story “Object Lesson.” Other paraphernalia include ads for McCrillus’ remedies and business cards for Riley’s sign painting business; Riley’s dress shirt studs; a label for vacuum-packed Hoosier Poet Coffee, featuring a rosy-cheeked Riley; a Cuban cigar, complete with leather case; and Riley’s inkwell.

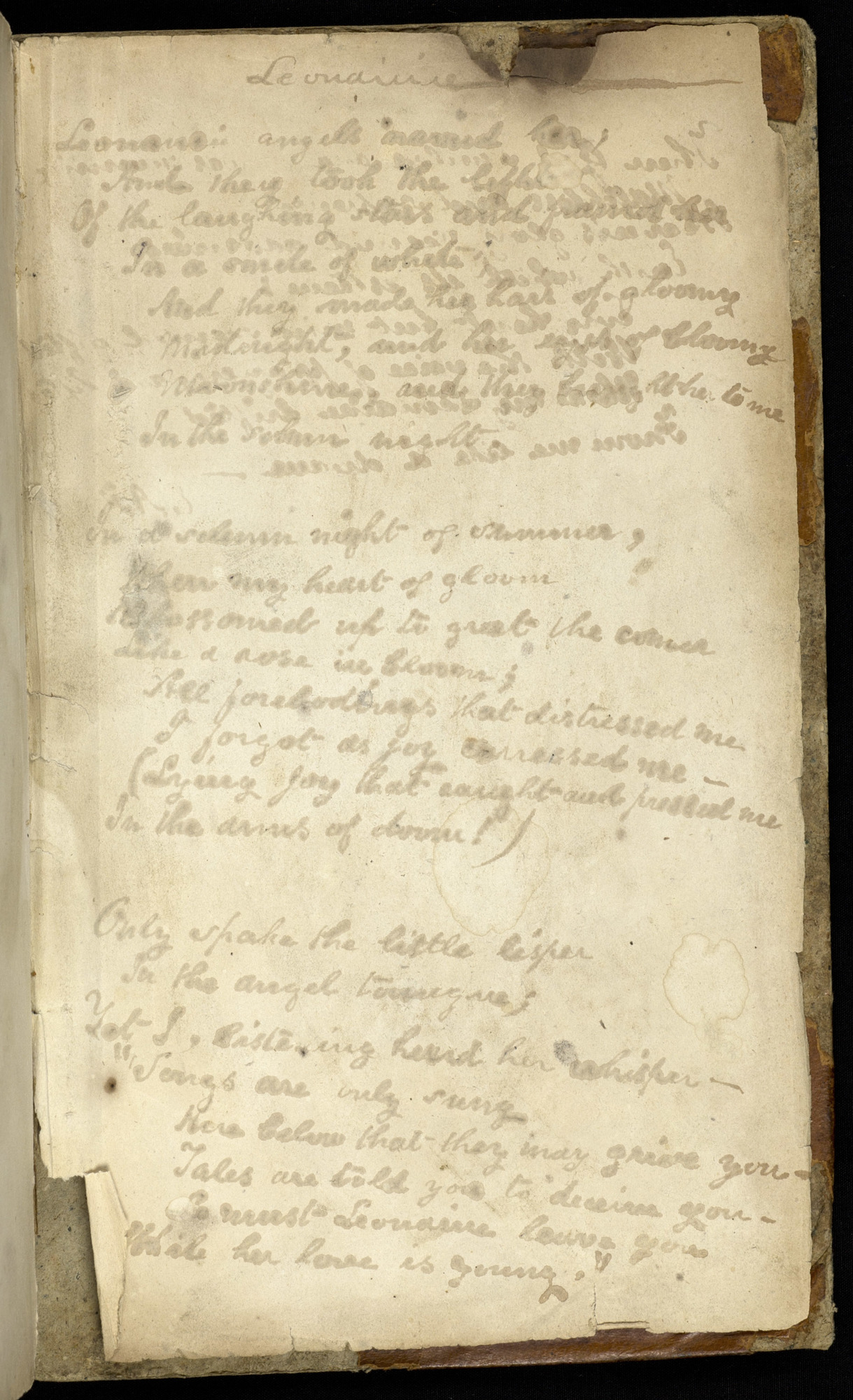

[James Whitcomb Riley], “Leonainie,” written on back flyleaf of An Abridgment of Ainsworth’s Dictionary, English and Latin, ca. 1850.

In 1875, Riley wrote and published an alleged Edgar Allan Poe poem, the result of an ill-advised bet with a friend. Responding to skeptical readers, Riley decided to fabricate the “original” manuscript. Using watered-down ink, a friend of Riley’s, the artist Samuel Richard, produced a manuscript in the back of this old dictionary. The handwriting not even faintly resembled that of Poe.

“The Poet Poe in Kokomo!”The Anderson Democrat, August 17, 1877

Many readers found it hard to believe Riley’s story that Poe had spent a night in an inn in Kokomo, leaving this poem behind as he departed. Riley’s poem does, if clumsily, use some of the elements of a typical Poe text, both in terms of subject (the death of a young woman) and form (the insistent alliteration of the letter L). When it became clear that Riley had forged “Leonainie,” he lost his job with the Anderson Democrat. Some remained unconvinced, most prominently the co-discoverer of evolution, Alfred Russel Wallace, who continued to spill ink on proving that Poe was the author of “Leonainie.” To a certain extent, then, Riley had made his point—that the name of the poet rather than the quality of the poem influences our response to a literary text—but he paid a terrible price for it.

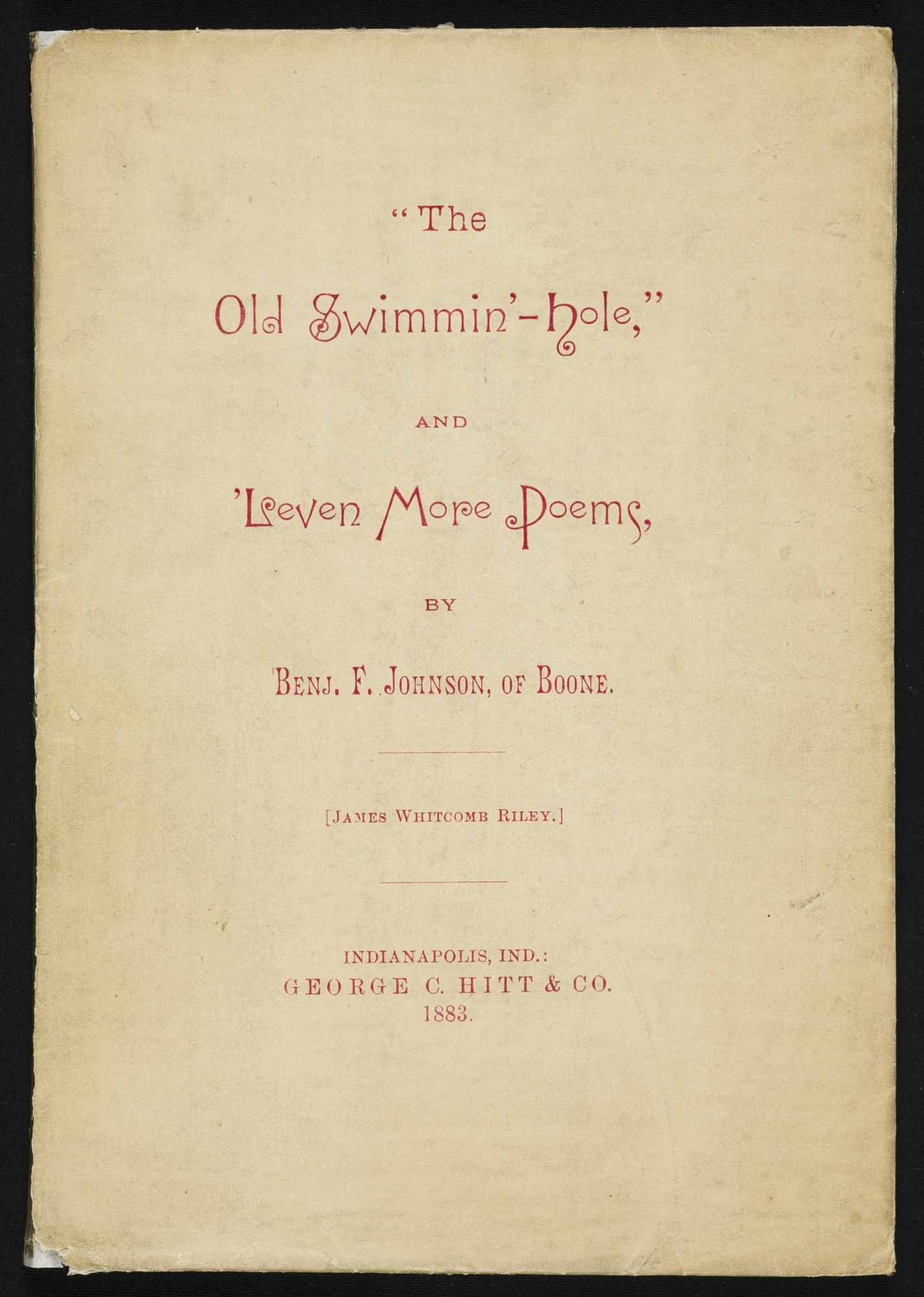

James Whitcomb Riley, The Old Swimmin’-Hole. Indianapolis: George C. Hitt, 1883.

Riley’s first volume of poetry, inscribed to painter T.C. Steele, with the lines: “It ain’t no use to grumble and complain; / Its jist as cheap and easy to rejoice.” The second copy displayed was given to fellow journalist Anna Nicholas. The poems, among them the now iconic “When the Frost is on the Punkin,’” had first appeared in the Indianapolis Journal, under the pseudonym “Benjamin F. Johnson,” the name that appears on the cover of this publication as well. But Riley is identified as the real author both on the front paper wrapper and in the Publisher’s Note. In the short preface, Riley cannily invokes Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, with a quotation from the latter’s “The Day Is Done.”

James Whitcomb Riley, “An Hour with Longfellow,” Indianapolis Journal, April 29, 1882.

The endorsement of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was then likely the world’s most famous poet, turned out to be crucial for Riley. A few short weeks before Longfellow’s death, Riley visited him at his mansion on Brattle Street in Cambridge, an experience Riley immediately communicated to readers back home. He was particularly gratified that Longfellow, with his well-known interest in understanding and promoting cultural diversity, had asked that Riley regale him “with a genuine bit of Hoosier dialect.”

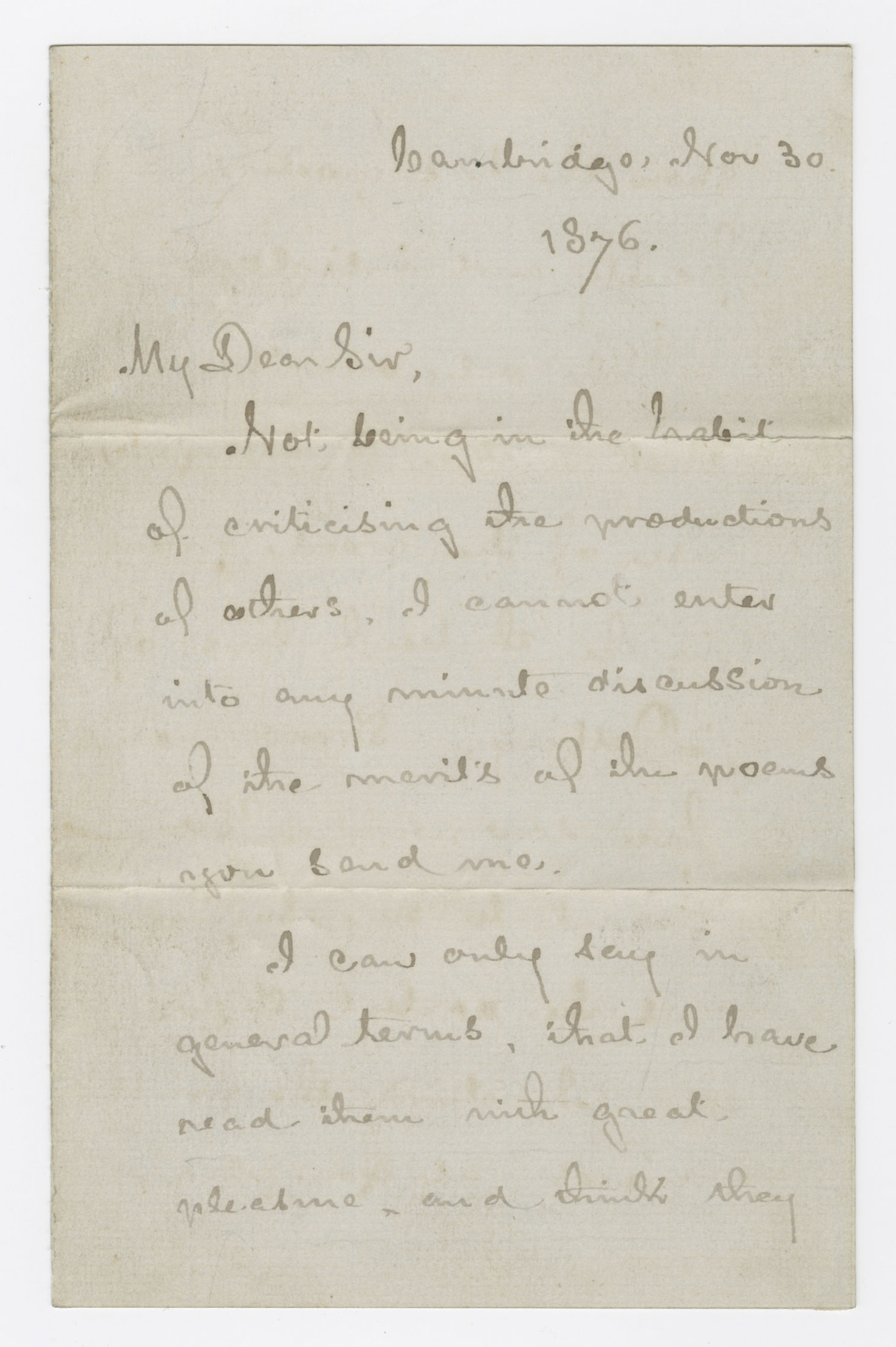

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to James Whitcomb Riley, November 30, 1876.

Although Riley was not shy about claiming publicly that his poetry had found Longfellow’s approval, the letters he received from the Cambridge poet were more circumspect. In this letter, Longfellow states his reluctance to evaluate the “productions of others” but then goes on to point out an error in one of Riley’s poem: “The only criticism I shall make is your use of the word prone in the thirteenth line of ‘Destiny.’ Prone means face-downward. You meant to say supine.”

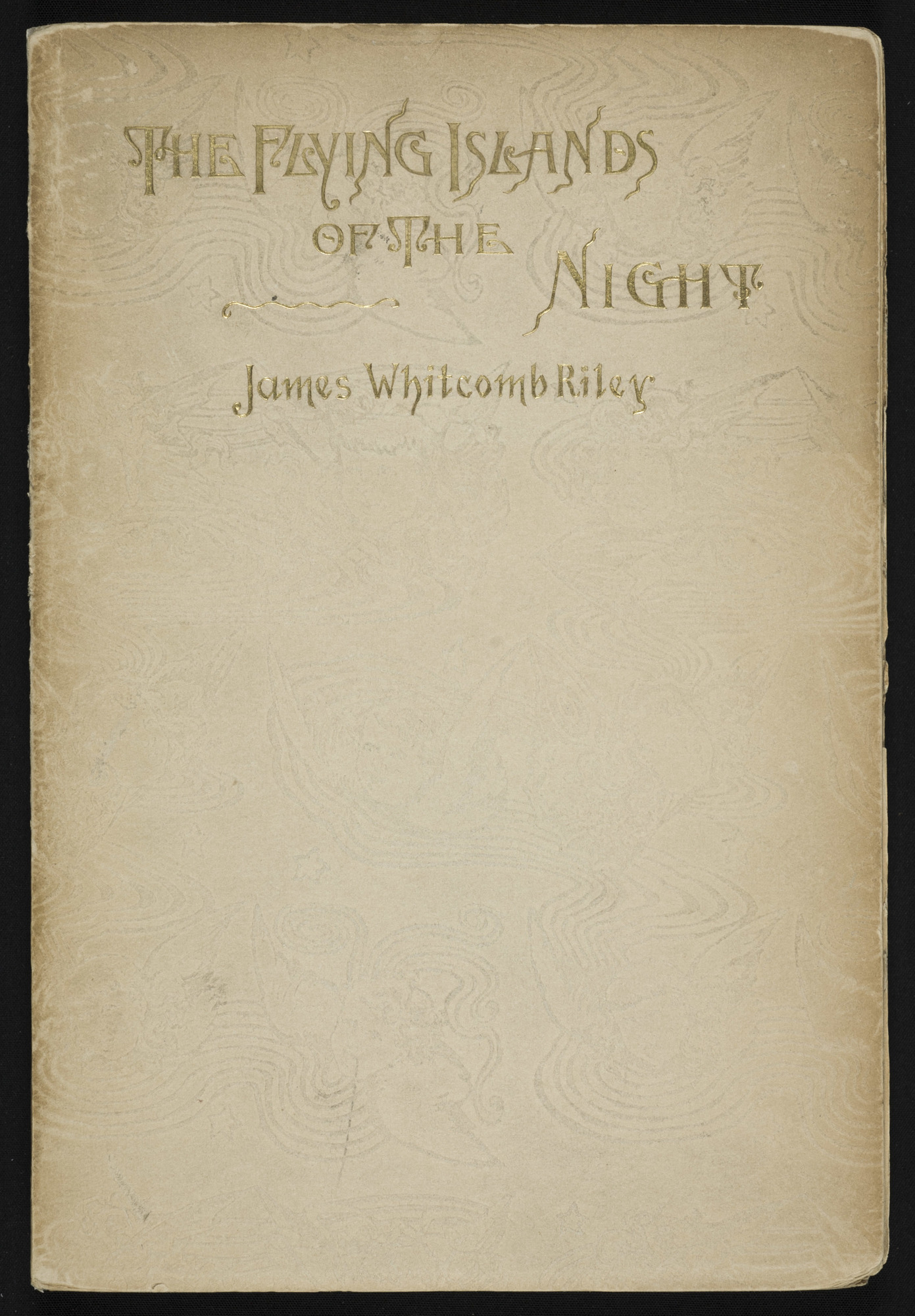

James Whitcomb Riley, The Flying Islands of the Night. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1892.

One of Riley’s strangest works, the only play he wrote. A fantastical three-act farce dealing with an evil queen unsuccessfully plotting the murder of her husband, it was likely influenced by Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with a healthy infusion of Carrollian nonsense: “What sings the breene on the wertling vine, / Ad the tweck on the banner stem?” Intoxication plays a major role in propelling the play’s plot—perhaps a trace of Riley’s own demons? This copy was dedicated to New England poet John Greenleaf Whittier, “with hale admiration and affection.” Riley’s association with Bowen-Merrill (later Bobbs-Merrill), the company that began when Samuel Merrill bought an Indianapolis bookstore in 1850, lasted for the rest of his life.

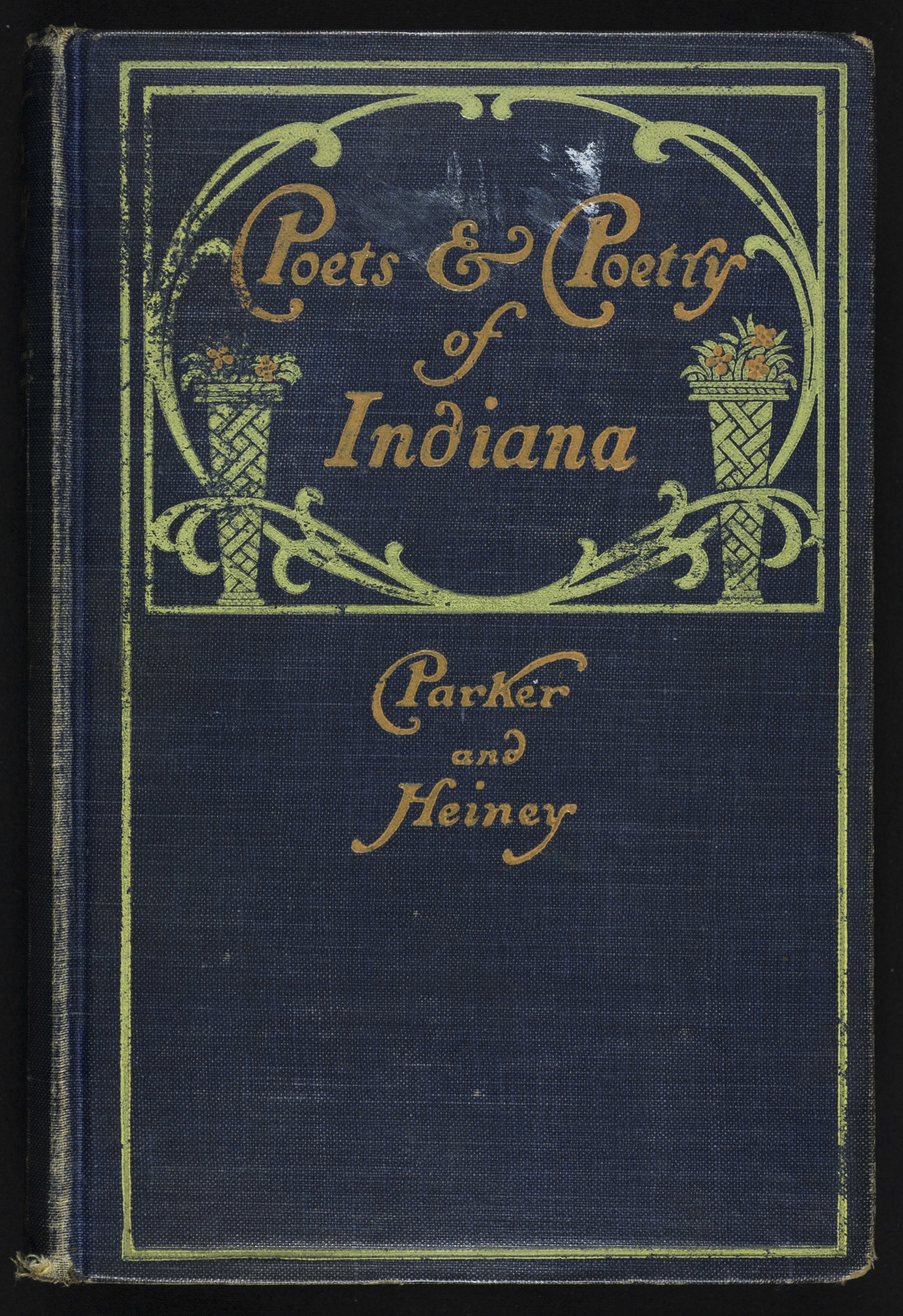

Poets and Poetry of Indiana: A Representative Collection of the Poetry of Indiana During the First Hundred Years of Its History as Territory and State, 1800 to 1900. Ed. Benjamin S. Parker and Enos B. Heiney. New York: Silver, Burdett, and Company, 1900.

The publication of this first comprehensive anthology of Hoosier poets also mars Riley’s anointing as “the most popular of American poets.” The editors also declare: “There is but one James Whitcomb Riley. Any adequate mention of the scope and character of his verse is impossible and would be superfluous, since he has a national reputation, and his poems are familiar to readers all over the nation.” Copy owned by Granville Wells, Herman B Wells’s father, with pencil notes identifying poems as “sonnet” or “standard.”

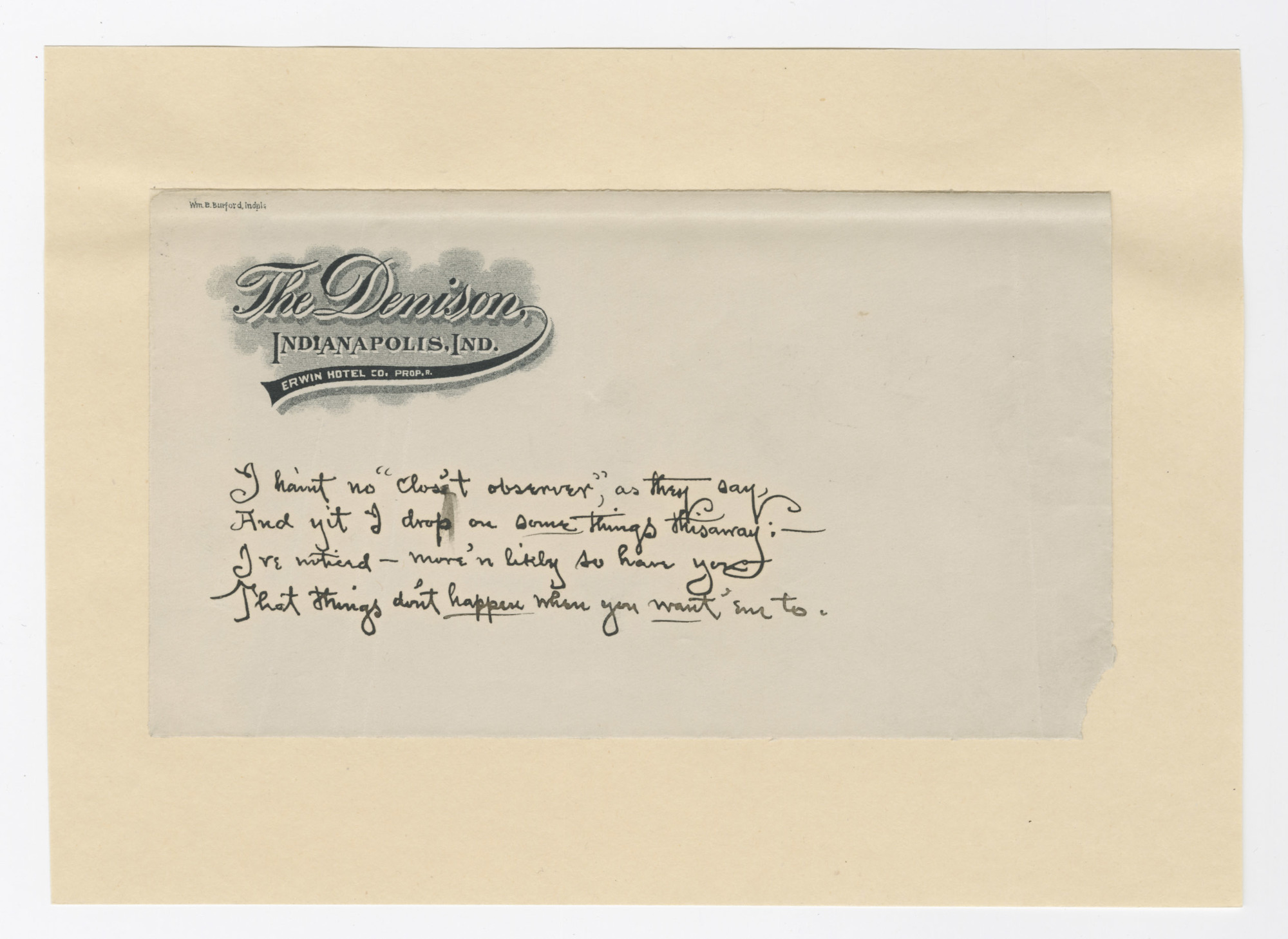

James Whitcomb Riley;“I haint no….” Undated note.

An example of Riley’s creative process. Many poems originated in lines jotted on envelopes, written, like this one, on hotel stationery. The four-liner contains Riley’s poetics in a nutshell, the recipe for his success: a commonplace sentiment packed into an imagined conversation with a reader who is on the same level as, if not superior to, the author, who is just saying what everyone thinks anyway.

“I haint no “close ‘t observer,” as they say

And yit I drop on some things this away:—

Ive noticed—more’n likely so have you-

That things don’t happen when you want them to.”

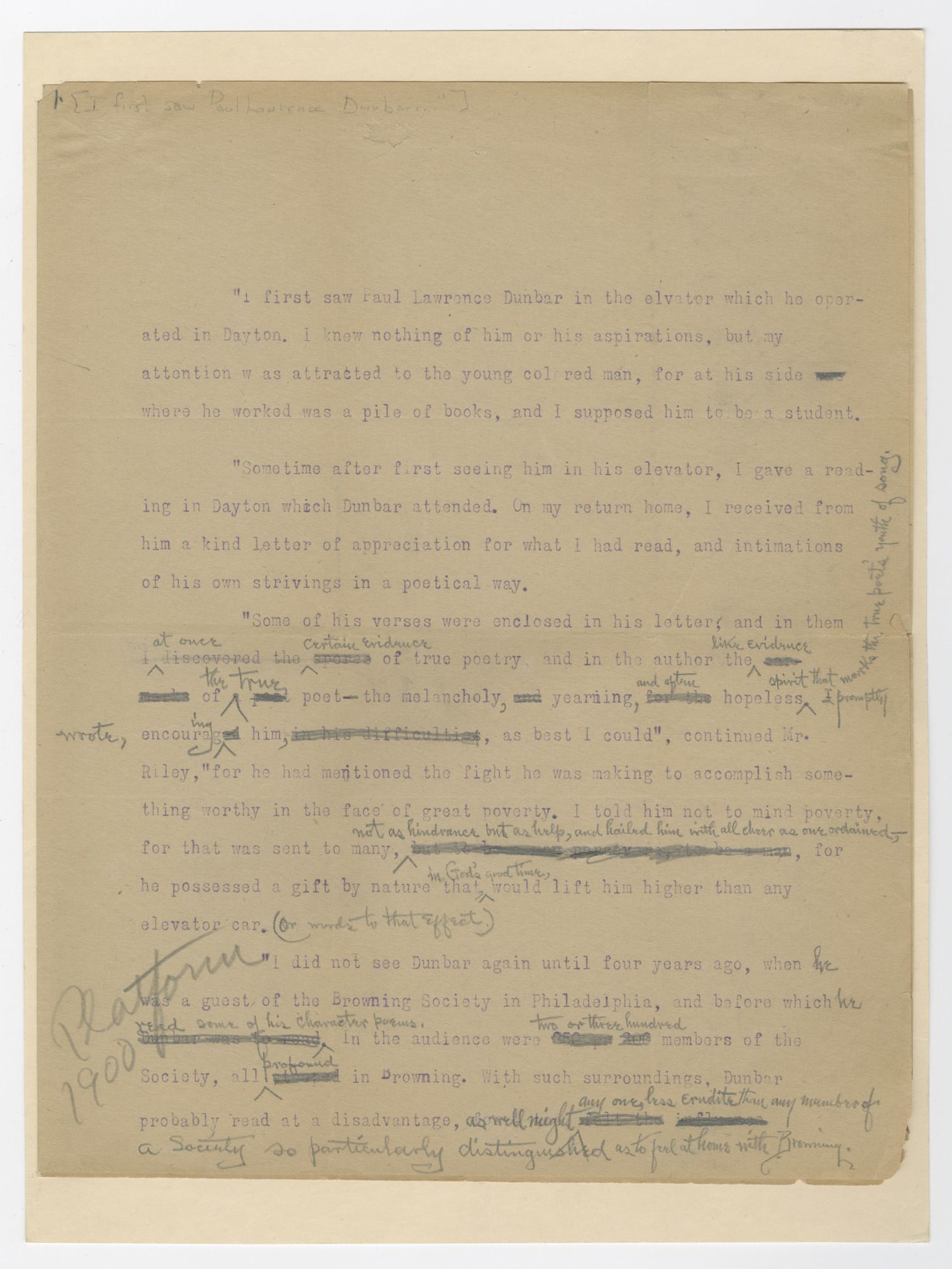

James Whitcomb Riley, “Paul Laurence Dunbar,” Typescript note, with holograph corrections.

With Riley’s holograph corrections. Riley fondly recalls his meetings with African-American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906). Unlike novelist William Dean Howells, who in 1896 had condescendingly introduced Dunbar’s Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) with the remark that here was the “first instance of an American negro who had evinced … innate distinction in literature,” Riley shows himself free of racial stereotyping when he celebrates Dunbar’s poetry as “that of a man.”

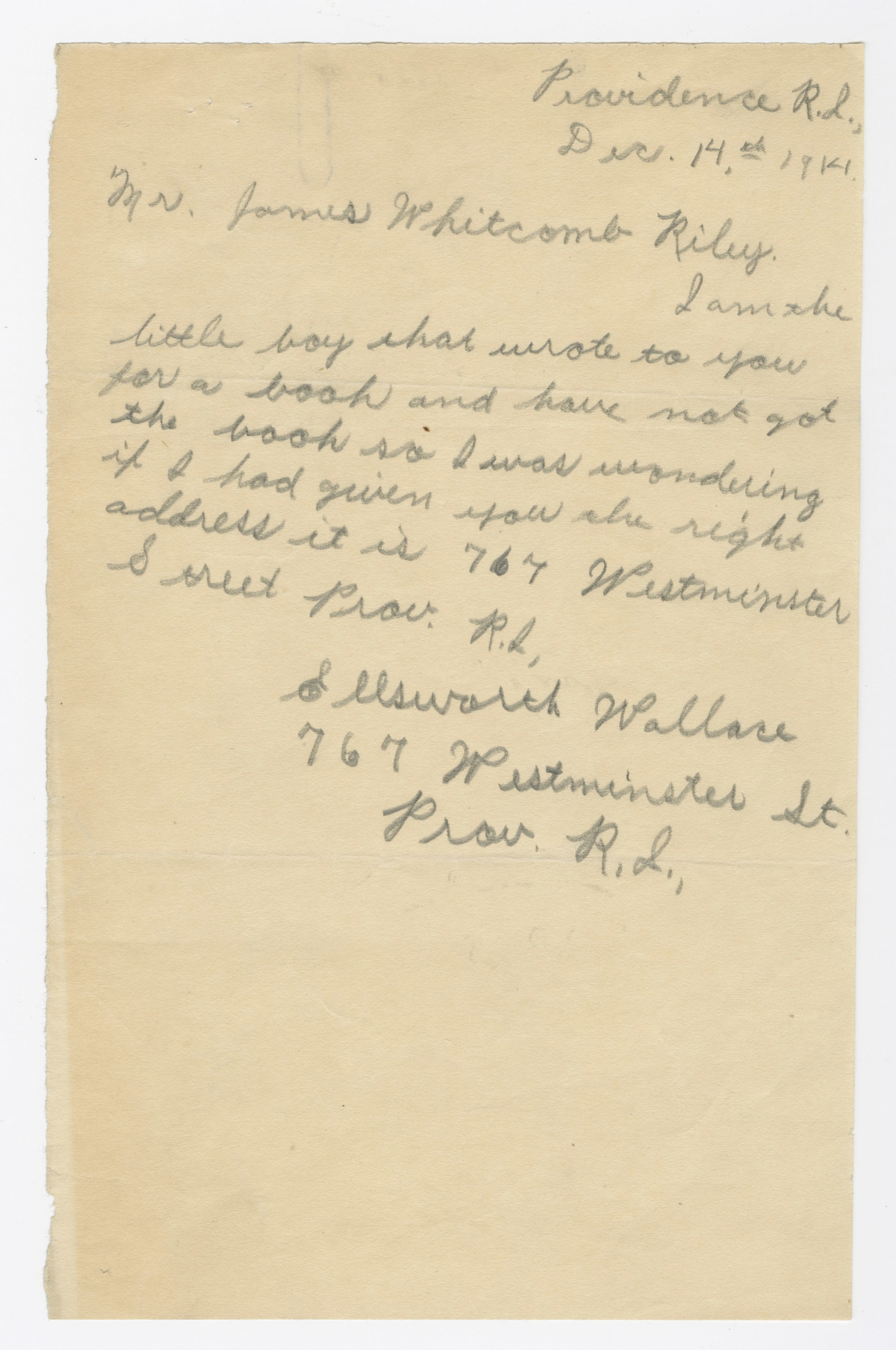

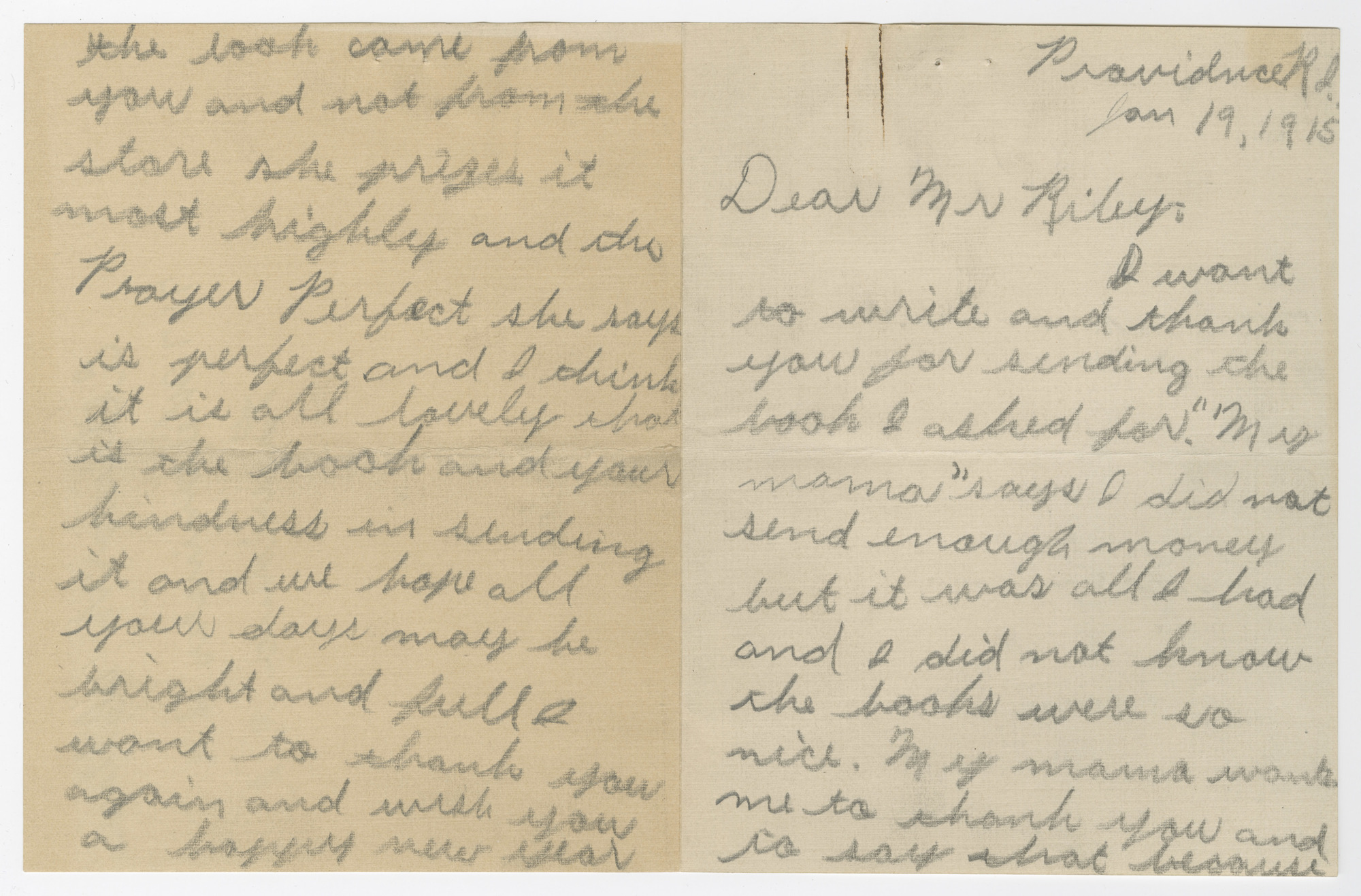

Ellsworth Wallace to James Whitcomb Riley, December 9, 14, 1914; January 19, 1915.

Young Ellsworth from Providence, Rhode Island, was just one of many children who, during the last two decades of Riley’s career, would write to him either to wish him well or to ask for specific favors, as was the case with Ellsworth: “Please send me one of your books Something that my mother will like. My Father has just died and my mother is pretty lonesome. I am quite a big boy of 9 years old. I am lonesome too because I have no brothers or sisters.” Unfortunately, Ellsworth forgot to include his address. Riley sprang into action, asking, through his secretary, that the Postmaster of Rhode Island locate the boy for him. Residents of Rhode Island came to the rescue, as shown here by Charles F. Towne’s response. Ellsworth himself belatedly realized his mistake (letter to Riley, December 14, 1914), but Riley had already solved the puzzle. On January 19, 1915, the final letter shown here, Ellsworth acknowledged receipt, apologized for not including sufficient postage (“I did not know the books were so nice”) and thanked his new hero: “I hope all your days may be bright and full.” A seemingly trivial exchange, this series testifies to the important role Riley played in the history of modern fan culture.

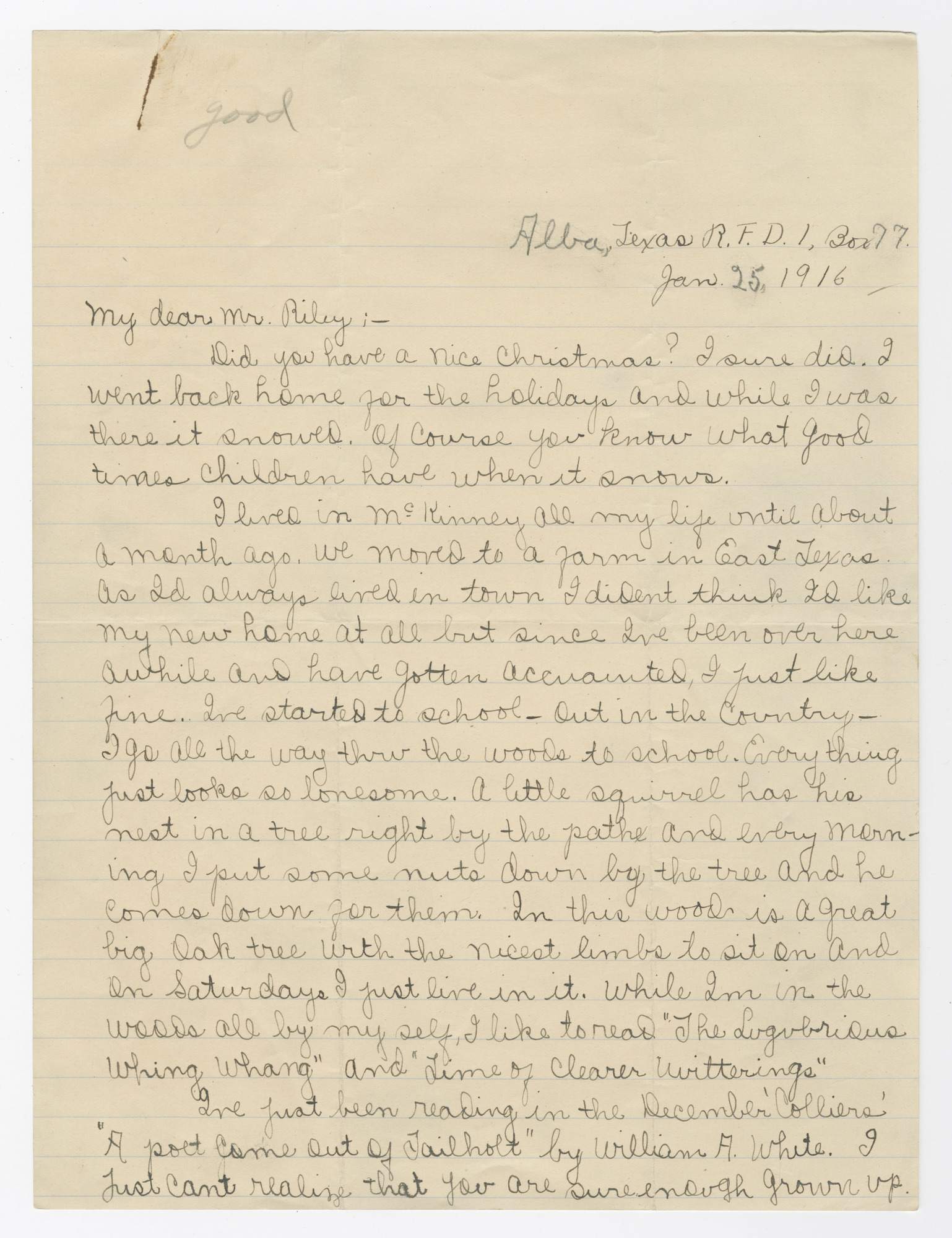

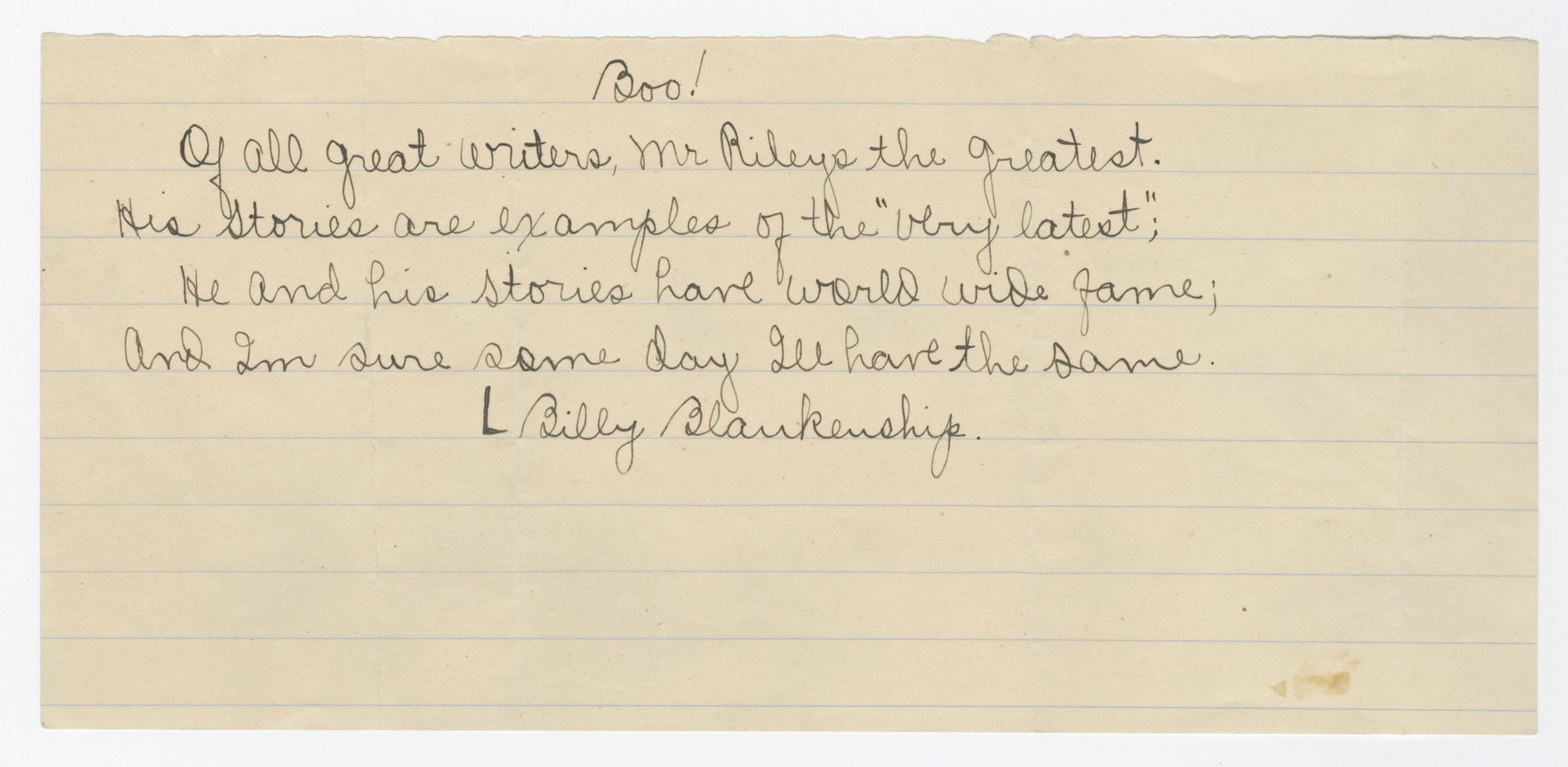

“Billy” Leta Blankenship to James Whitcomb Riley, January 25, 1916.

Leta Blankenship, originally from McKinney Texas and recently relocated to Alba in East Texas, preferred to be known as “Billy,” in line with the tomboy behavior spelled out in her letter. A die-hard fan of Riley’s poetry, she reads it to her friends in school. As Riley once was, she is an indifferent student: “Mr Riley, I sure am bad in school. My teacher said, ‘Billy I sure am glad you are not twins. I try to be good, sometimes…” Billy also includes a sample of her own poetry, titled “Boo!,” perhaps remembering Riley’s interest in the goblins “’at gits you” if you don’t watch out:

Of all great writers, Mr Rileys the greatest.

His stories are examples of the “very latest”;

He and his stories have world wide fame;

And Im sure some day Ill have the same

L. Billy Blankenship

Through his secretary, Mr. Riley responded, addressing Leta as “Billy” (as desired) and sending her a booklet with his poems.

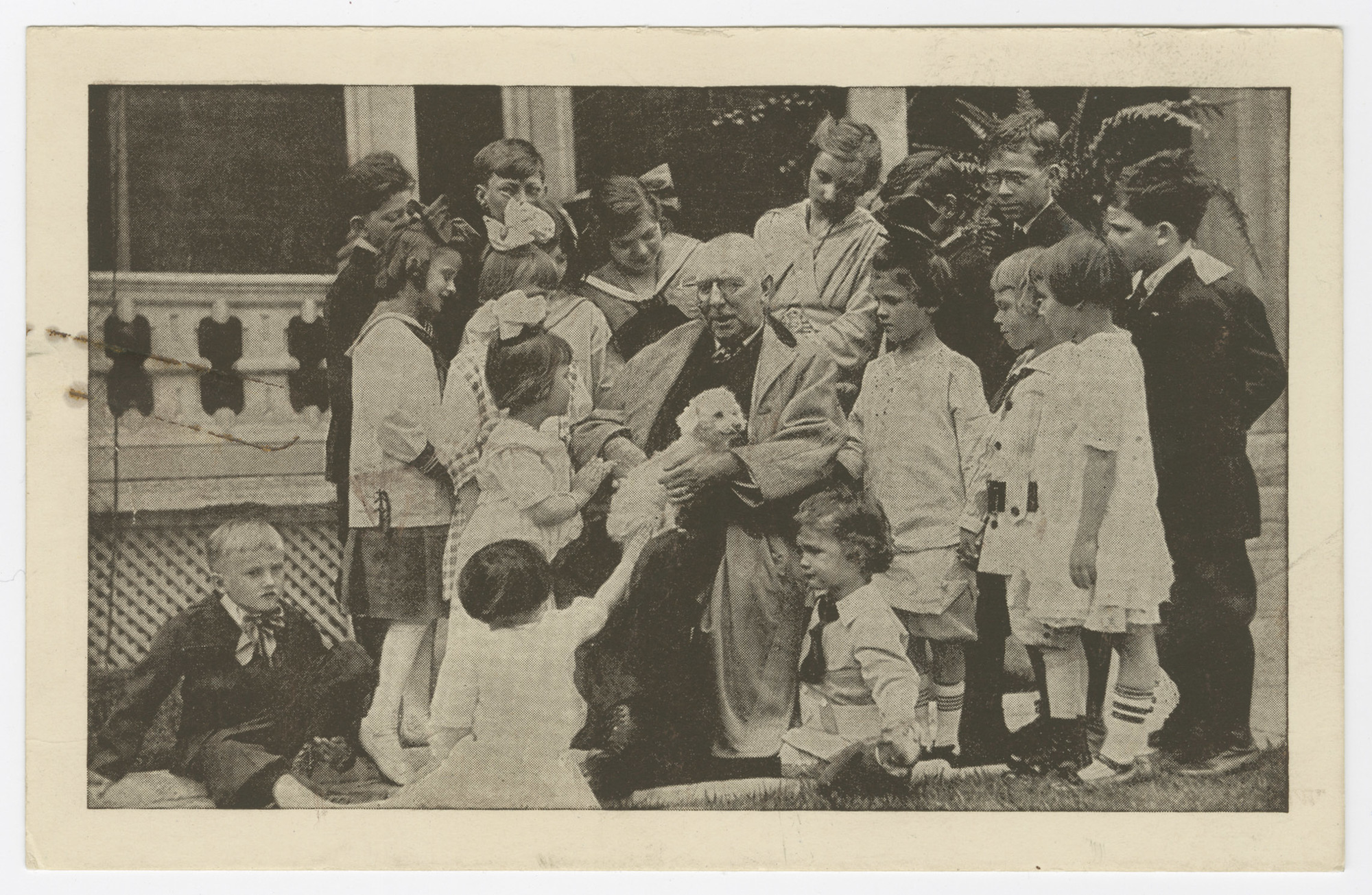

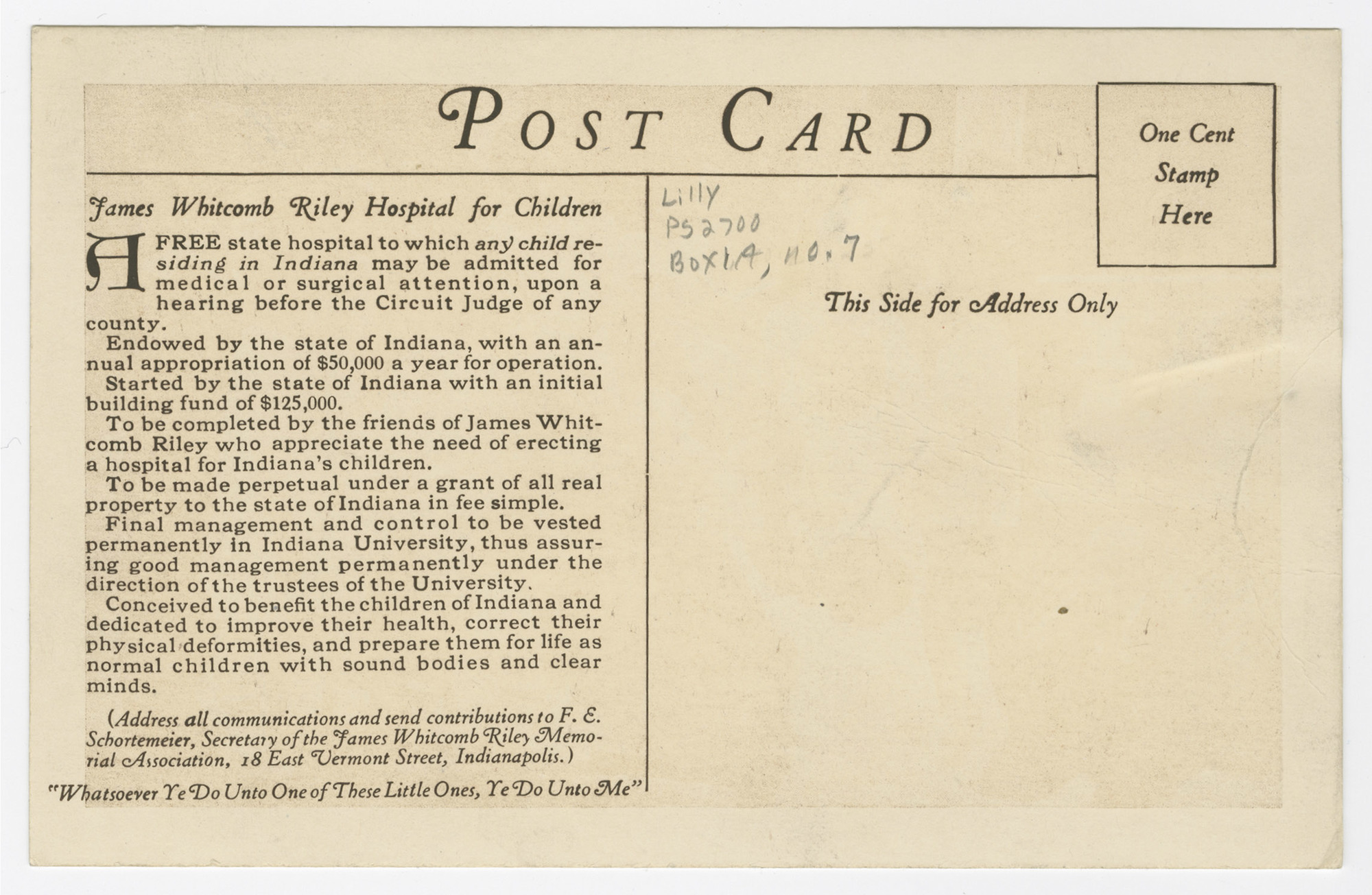

Promotional postcard for Children’s Hospital, “to benefit the children of Indiana and dedicated to improve their health,” undated.

Photograph showing Riley in front of this Indianapolis home, with his dog Lockerbie and surrounded by children. The James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association, founded in 1921 in honor of Riley, first purchased Riley’s home, opening it to the public, and then campaigned for a hospital named after him, “to benefit the children of Indiana and dedicated to improve their health.” Riley Hospital opened its doors and received its first patient in 1924.

Janette Covert Nolan, James Whitcomb Riley: Hoosier Poet. Special limited Indiana edition, Copy No. 575. New York: Julian Messner, 1941.

Inscribed to “President Herman B Wells, with best wishes, Janette Nolan, Bloomington, October 12, 1941” and signed by the illustrator, Robert S. Robison. From the library of Herman B Wells.

Born on March 31, 1897 in Evansville, Indiana, where her father served as mayor and postmaster, Nolan wrote over forty-five children’s books. Her husband, Val Francis Nolan, whom she survived by more than three decades, was a Trustee of Indiana University.