Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was born into a family of wealthy German Americans in Indianapolis. His father, Kurt Sr., was the mediocre son of Bernard Vonnegut, owner of the architectural firm of Vonnegut & Bohn, whose vision had manifested itself in iconic Indianapolis buildings such as the John Herron School of Art, the Pembroke Arcade, and the Deutsches Haus, as well as in the Student Building on the campus of Indiana University Bloomington. Family wealth afforded excellent educational opportunities to Kurt and siblings Alice and Bernard Jr., including family vacations on Cape Cod. Looking back, Kurt remembered feeling lonely in the big brick house at 4401 North Illinois Street, “where nobody was home for long periods of time.” The decline of his father’s fortunes meant adjustments to their lives that Vonnegut’s mother could not tolerate; she committed suicide in 1944, three months before Vonnegut Jr., who had dropped out of Cornell, was deployed to Europe. Vonnegut survived the devastating bombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war three stories underground. He was subsequently ordered to help locate and clean up the bodies under the rubble, an experience that cast a shadow over the rest of his career as a writer. It took Vonnegut almost two decades to be able to write about his war experiences. The darkly funny novel Slaughterhouse-Five, published in 1969, became his best-known work. In the last three decades of his life, Vonnegut reluctantly became a cultural icon, a kind of moral conscience of the nation, a public intellectual deeply skeptical of the capacity of “big brains” to solve the world’s problems.

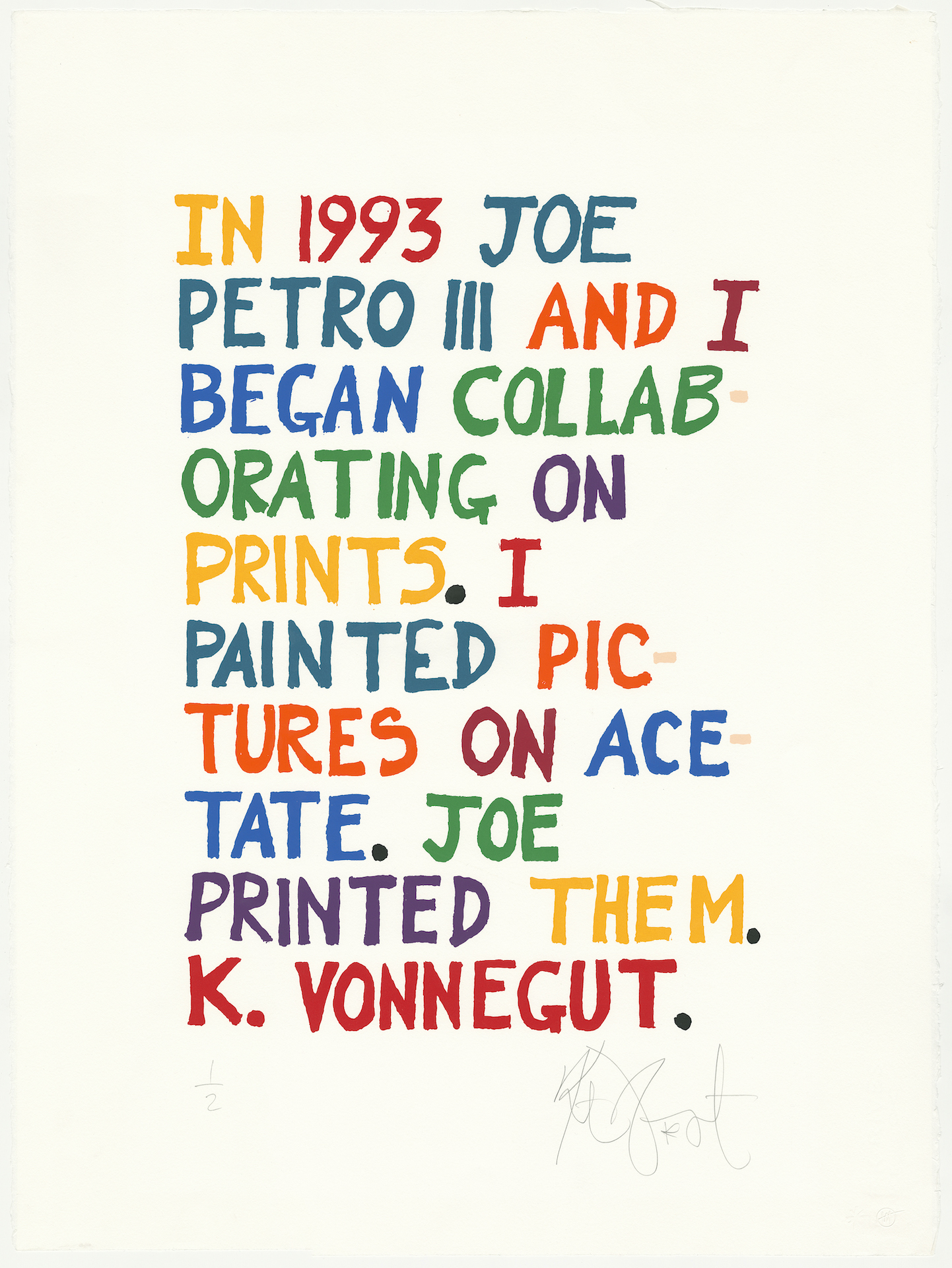

Kurt Vonnegut and Joe Petro III, “In 1993 Joe Petro III / and I….” Silkscreen print, 1993. Artist’s print.

Signed by Kurt Vonnegut, who liked to claim that, thanks to the architects in his family, he had an affinity for the visual arts too. As his father’s architectural career was faltering, he indeed turned to painting, although the many self-portraits he undertook often remained unfinished. Vonnegut Jr. had always doodled, but his collaboration with the Lexington-based artist and printmaker Joe Petro III marked a new stage in his understanding of art. Perhaps it was also the memory of his father’s unfinished projects that drove him. Vonnegut had known nothing about silkscreen printing, and what Petro taught him filled him with awe, as he explained in Man Without a Country (2005): “Joe makes prints of some of (my work), one by one, color by color, by means of the time-consuming, archaic silk screen process, practiced by almost nobody else anymore: squeegeeing inks through cloths and onto paper. This process is so painstaking and tactile, almost balletic, that each print Joe makes is a painting in its own right.” Of course, he wouldn’t have been Vonnegut if his art, transported into such a fine medium, had lost its edge.

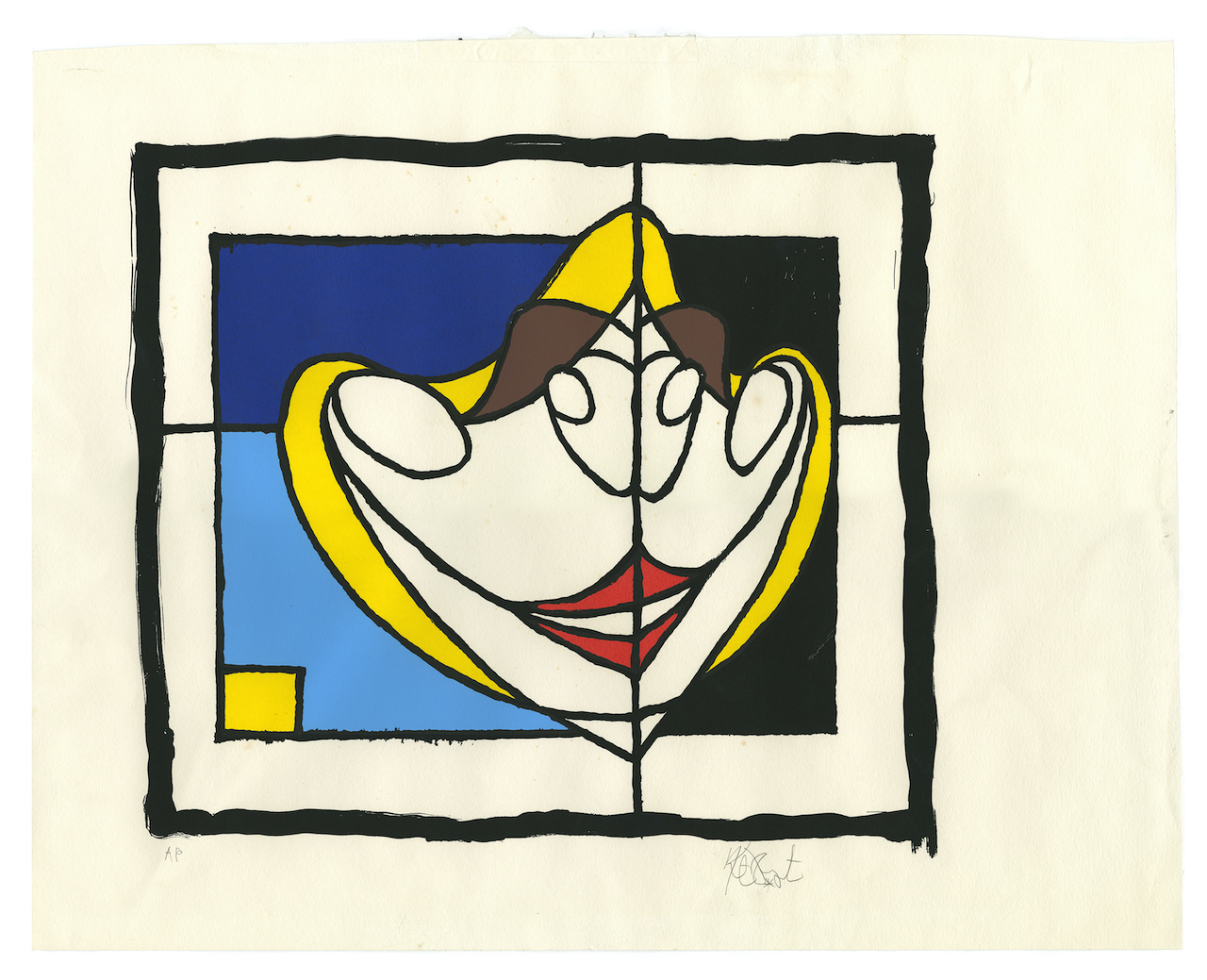

Kurt Vonnegut and Joe Petro III, “Three Madonnas.” 4 color silkscreen print on white Rives BFK cotton paper, 25 3/4 x 22 inches, 1993.

The abstract image could be taken to represent three women fused together, but viewed as a whole (instead of as a series of fragments), it suggests less holy union than a woman’s reproductive system. Vonnegut’s largely dismal view of human sexuality asserts itself. But other elements—the heart-shaped form of the creature, the almost balletic lightness indicated by the way it is positioned—complicate such a reading. The image thus perfectly summarizes the conflicting impulses in Vonnegut’s work, the satirical and the poetic, the destructive and the creative, and it does so with an immediacy that is easier to achieve in art than with words. The sharp edges and abstract forms remind the viewer of Vonnegut’s early tribal doodles, but the bright colors come from his experience in advertising, his belief that true art needs to sell.

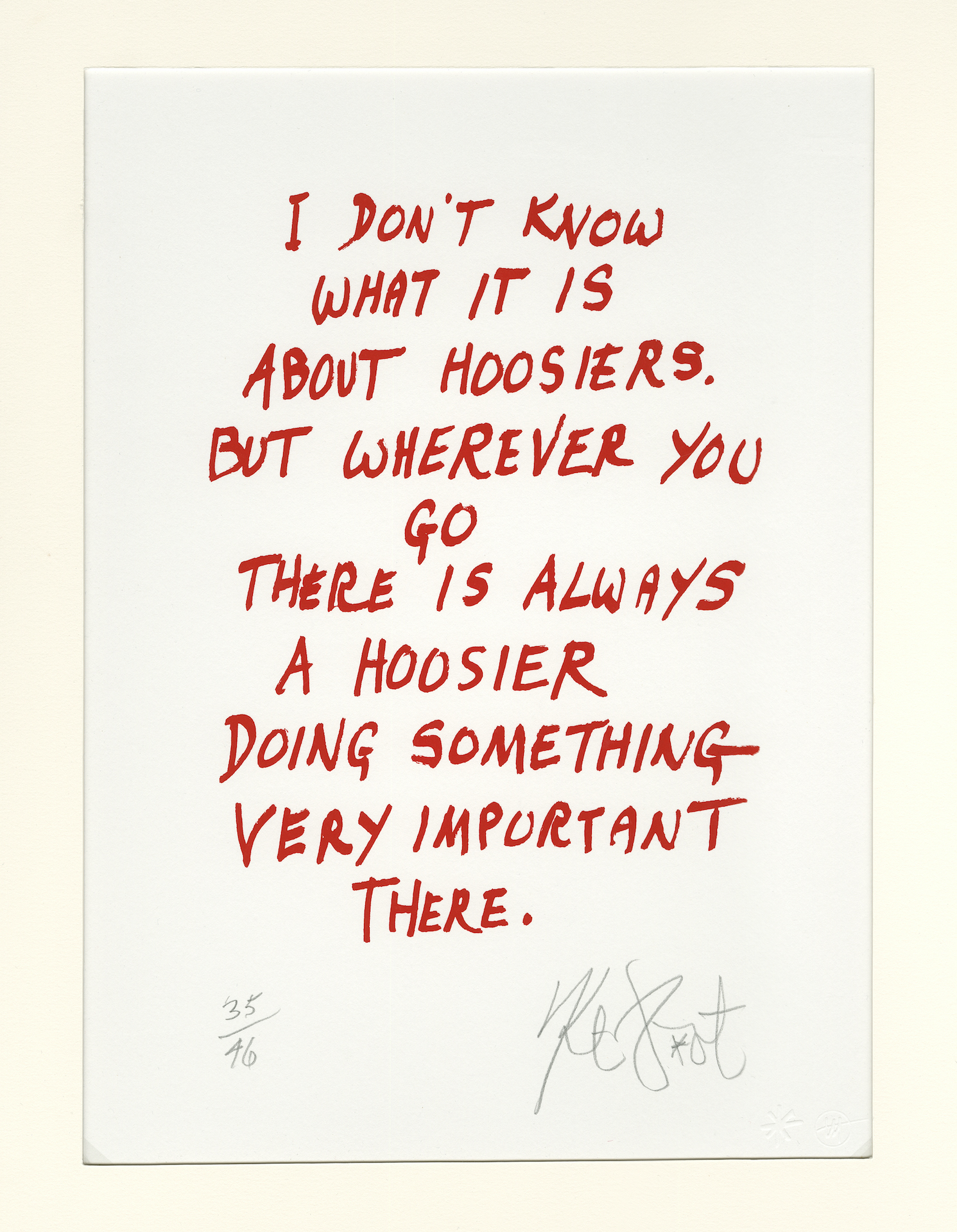

Kurt Vonnegut and Joe Petro III, “I Don’t Know What It Is About Hoosiers,” One color silkscreen print on white Coventry cotton paper, 11 x 15 inches, 2004. No. 35 of 46.

No. 19 of Vonnegut’s “Confetti Prints.” Signed in pencil by the artist. The sentiment in this print is reminiscent of an exchange in Cat’s Cradle (1973):

“My God,” she said, “are you a Hoosier?”

I admitted I was.

“I'm a Hoosier, too,” she crowed. “Nobody has to be ashamed of being a Hoosier.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I never knew anyone who was.”

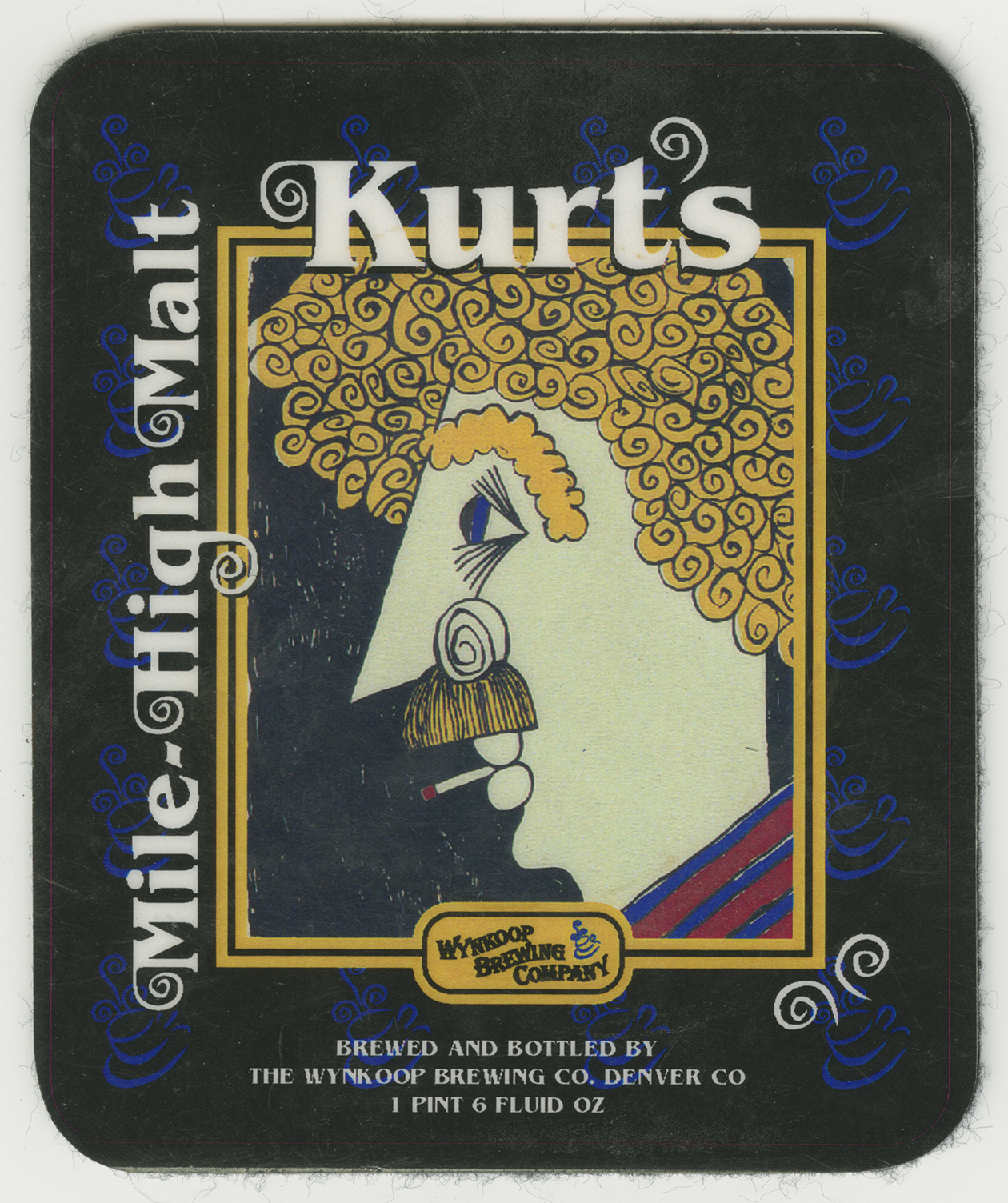

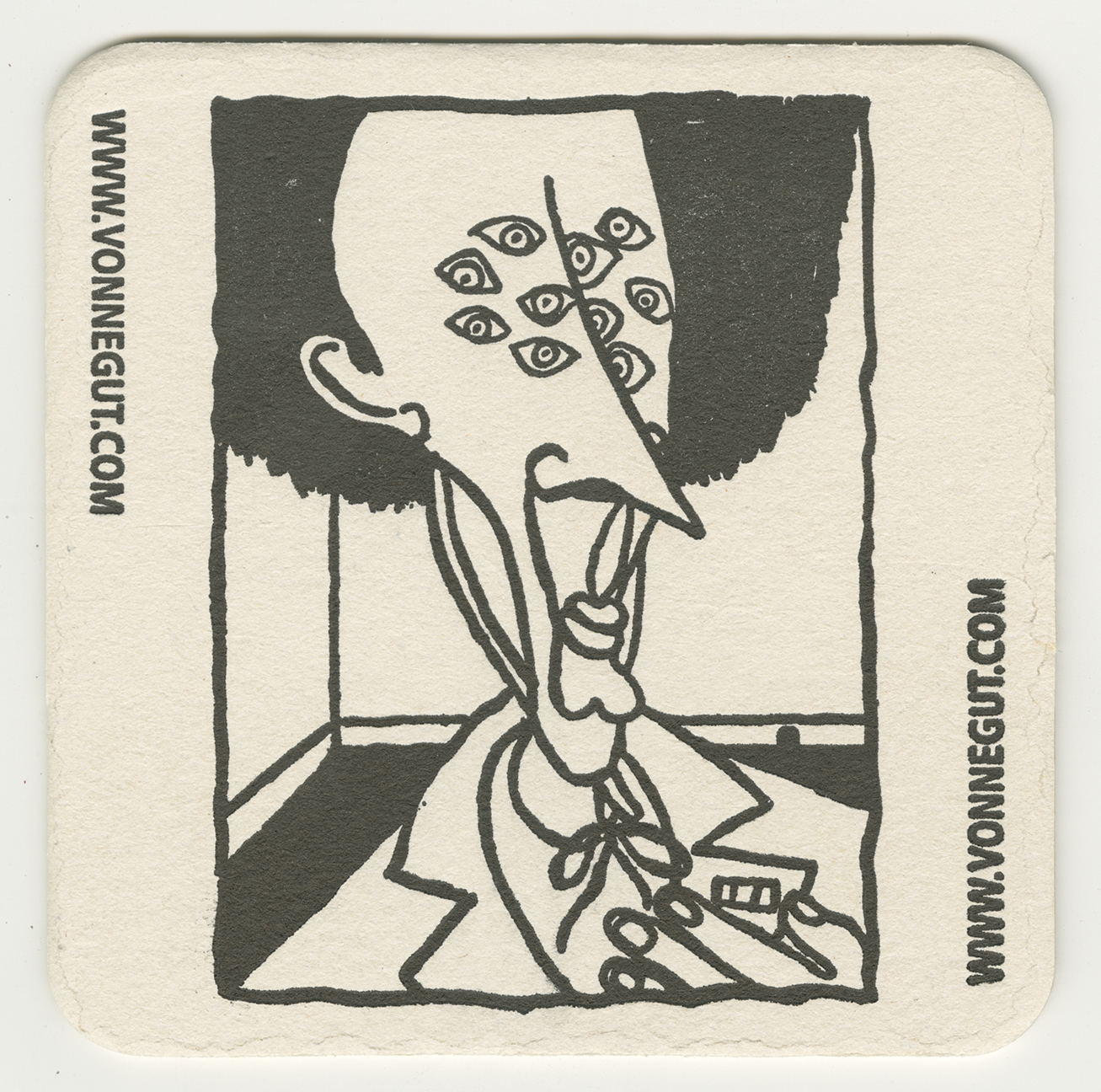

Coaster for “Kurt’s Mile-High Malt,” undated.

In 1996, the imaginative Mayor of Denver, John Hickenlooper, commissioned a series of short stories for labels to be affixed to a new series of brew, the “Denver Public Libation,” which had been launched to benefit a new library in town. Kurt Vonnegut agreed and when he came for a visit, the local Wynkoop brewery created two new flavors in his honor. One, Kurt’s High Mile Malt, was made after a recipe used by grandfather Albert Lieber, a brewer in Indianapolis, who would add coffee to his Dortmund-style lager and won a gold medal for his concoction at the Paris International Exposition in 1889. The coaster was made after the label. For the image, Kurt Vonnegut used his print “Self-Portrait #1 with Yellow Hair.”

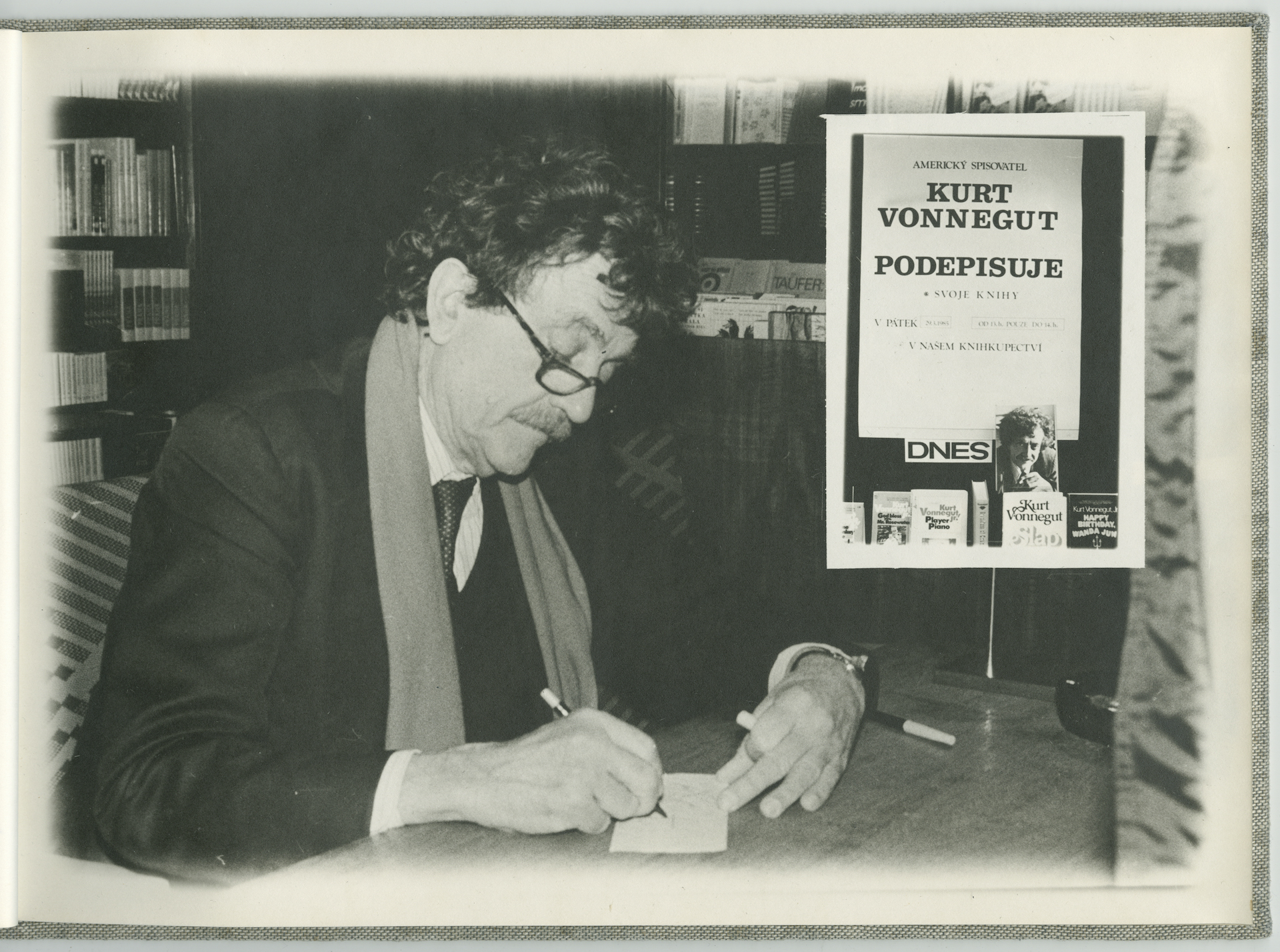

Private album of photographs depicting Kurt Vonnegut’s visit to Prague in 1985.

A great supporter of the Czech dissident movement, Vonnegut visited Czechoslovakia as a guest of the American Embassy and made a point of meeting with cultural figures persecuted by the regime. Several of the activists he met were members of the “Jazz Section,” an independent cultural group that used jazz music as a cover for underground cultural work. When several of his friends were arrested in 1986, Vonnegut wrote an op-ed for the New York Times, “Can’t They Even Allow Jazz?”: “Of all the triumphs of life-haters today, of fun-haters today, of beauty haters today, of thought-and-love haters today, of the Forces of Satan, if you will, the one that most troubles my heart is the inducement of some Czechoslovak politicians and police to behave like cannibals toward the most humane and generous and gifted members of their society.”

Coaster made after Black Heart, a 2004 silkscreen print by Kurt Vonnegut and Joe Petro III.

The silkscreen print, itself a copy of an earlier image titled Purple Heart, features Vonnegut’s fictional alter ego Kilgore Trout, an unsuccessful author of science fiction paperback novels who appears in several of Vonnegut’s works, notably in Breakfast of Champions (1973), where another character, Dwayne Hoover, bites off part of his right ring finger. Galápagos is narrated by Leon Trotsky Trout, the son and only child of Kilgore Trout. Like Vonnegut, Kilgore was awarded a purple heart (“for frostbite,” as Vonnegut liked to quip, too), though his post-war life unfolded in a different manner, as the caption of Purple Heart explains: Kilgore had posed for his portrait in 1947 in Skokie, Illinois, “where was employed by a diaper service.”

Unknown photographer, Schnull/Vonnegut Family Photograph, ca. 1895

Taken at the home of Henry Schnull, Kurt Vonnegut’s great-grandfather, a prominent wholesale merchant who lived at 13th Street and Central Avenue. Kurt Vonnegut Sr., the father of the novelist, appears standing on the left, before the left pillar, wearing a white and a black bow tie. Bernhard, the novelist’s grandfather, is standing right next to him; Bernhard’s wife, Nanette Schnull, sits on a chair in front of Bernhard and Kurt, Sr., her arm against the back of the novelist’s uncle, Alex.

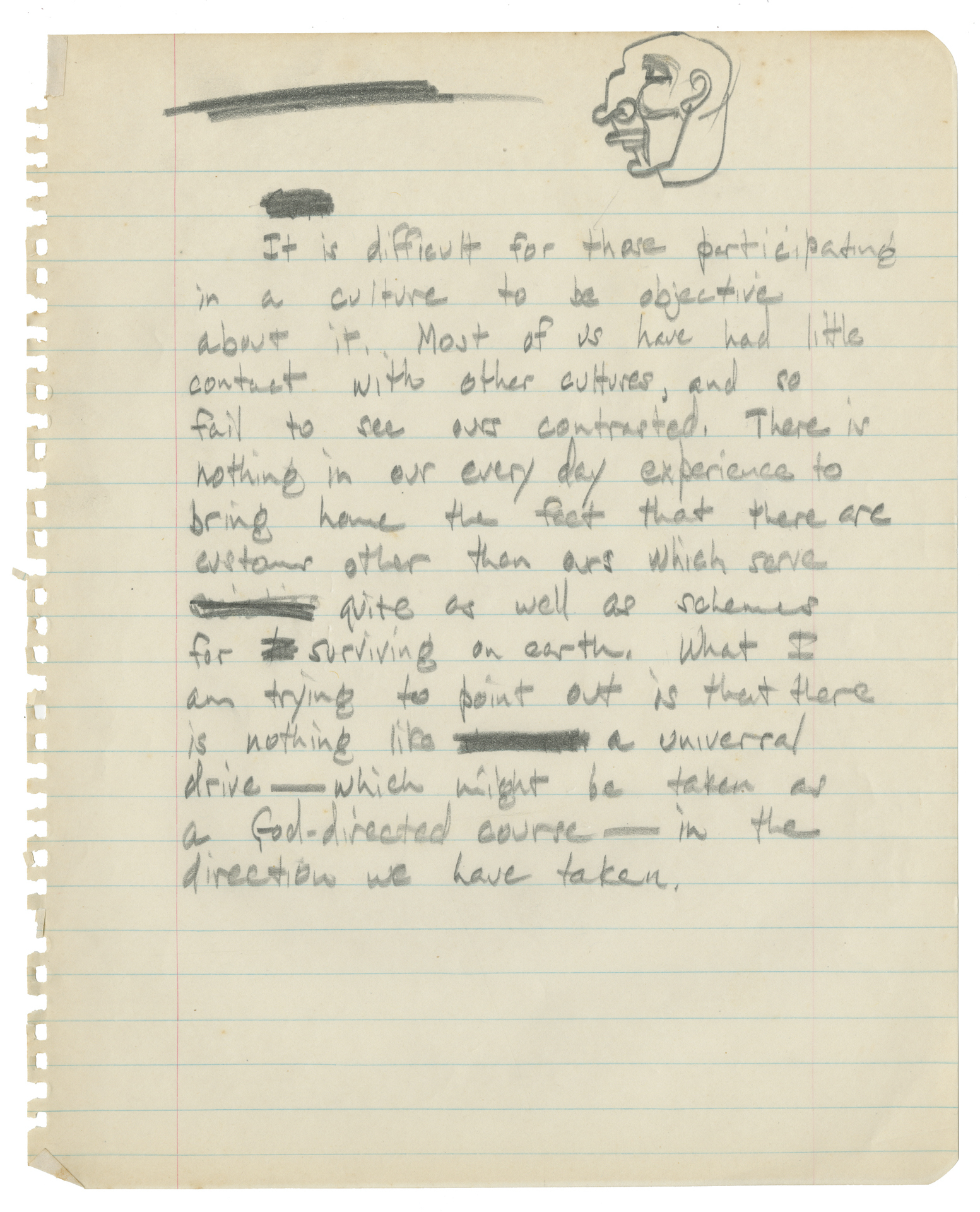

Kurt Vonnegut, Class Materials from Anthropology 499, ca. 1945.

In 1945, Vonnegut enrolled at the University of Chicago through the GI Bill, taking graduate classes in anthropology. While his doodles might indicate less than fervent interest in the material, the actual notes reveal that his studies were not in vain and have left their traces in his fiction. All cultures are different, he states, and cannot be viewed objectively by inside observers: “What I am trying to point out is that there is nothing like a universal drive—which might be taken as a God-directed course—in the direction it [culture] has taken.”

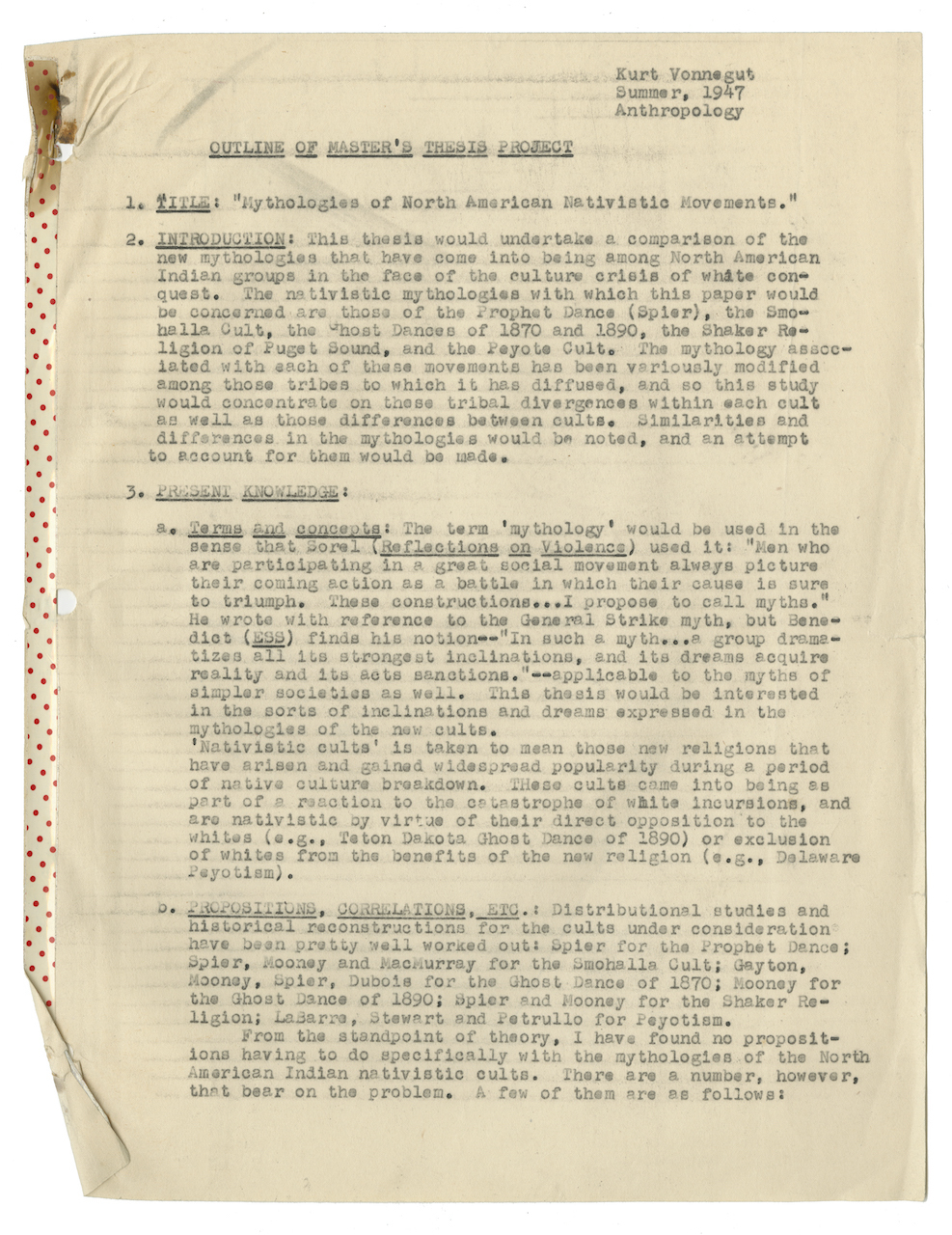

Kurt Vonnegut, Outline of Master’s Thesis Project, “Mythologies of Native American Movements,” Summer of 1947.

Vonnegut’s second attempt at suggesting a topic acceptable to his professors, replacing an earlier idea for a project that would have involved a comparison between leaders of Native American uprisings and Cubist painters in Paris. Vonnegut’s professors took a more favorable view of the new plan, but Vonnegut had apparently run out of steam and quit the program. In 1970, after Vonnegut had been invited to teach at Harvard and his lack of a degree turned out to be a problem, he requested that the Anthropology Department give him a second chance and consider one of his novels in lieu of a proper Master’s thesis. The faculty complied and accepted Cat’s Cradle (1963), on the basis of its portrayal of island culture and religion, as an adequate substitute.

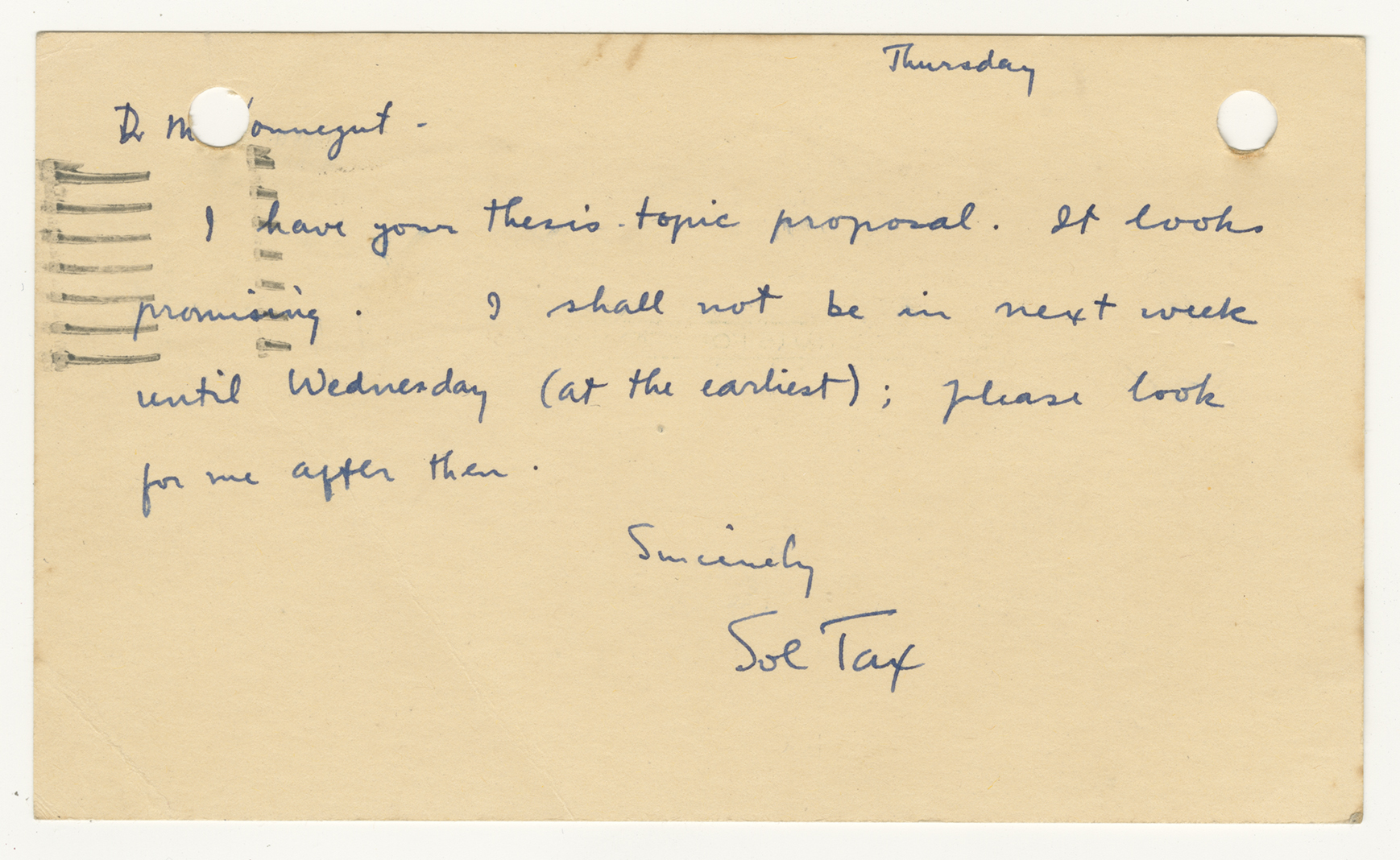

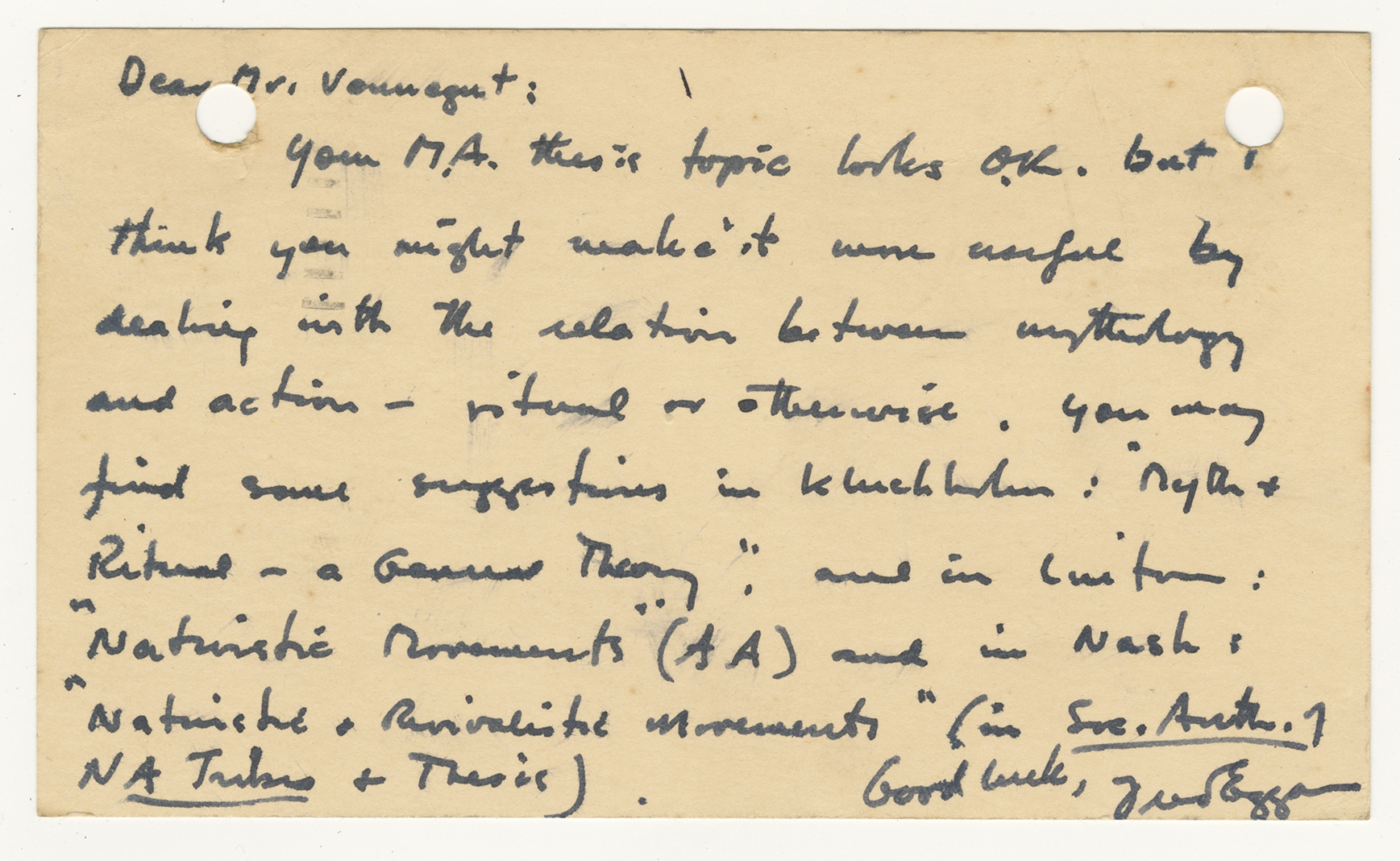

Sol Tax and Fred Eggan to Kurt Vonnegut, July 24 and 25, 1947

Both Eggan and Tax specialized in the study of Native American cultures. On display are the front of Tax’s postcard and the verso of Eggan’s postcard to Vonnegut: “Dear Mr. Vonnegut,” writes Eggan. “Your M.A. thesis topic looks OK, but I think you might make it more useful by dealing with the relation between mythology and action—ritual or otherwise. You may find some suggestions in Kluckhohn: ‘Myth and Ritual—A General Theory’, and in Linton: ‘Nativistic Movements’ (AA) and in Nash: ‘Nativistic and Revivalistic Movements’ (in Soc. Anth. of NA Tribes + Thesis). Good luck, Fred Eggan.” Professor Tax was more succinct: “Dear Mr. Vonnegut: I have your thesis proposal. It looks promising.”

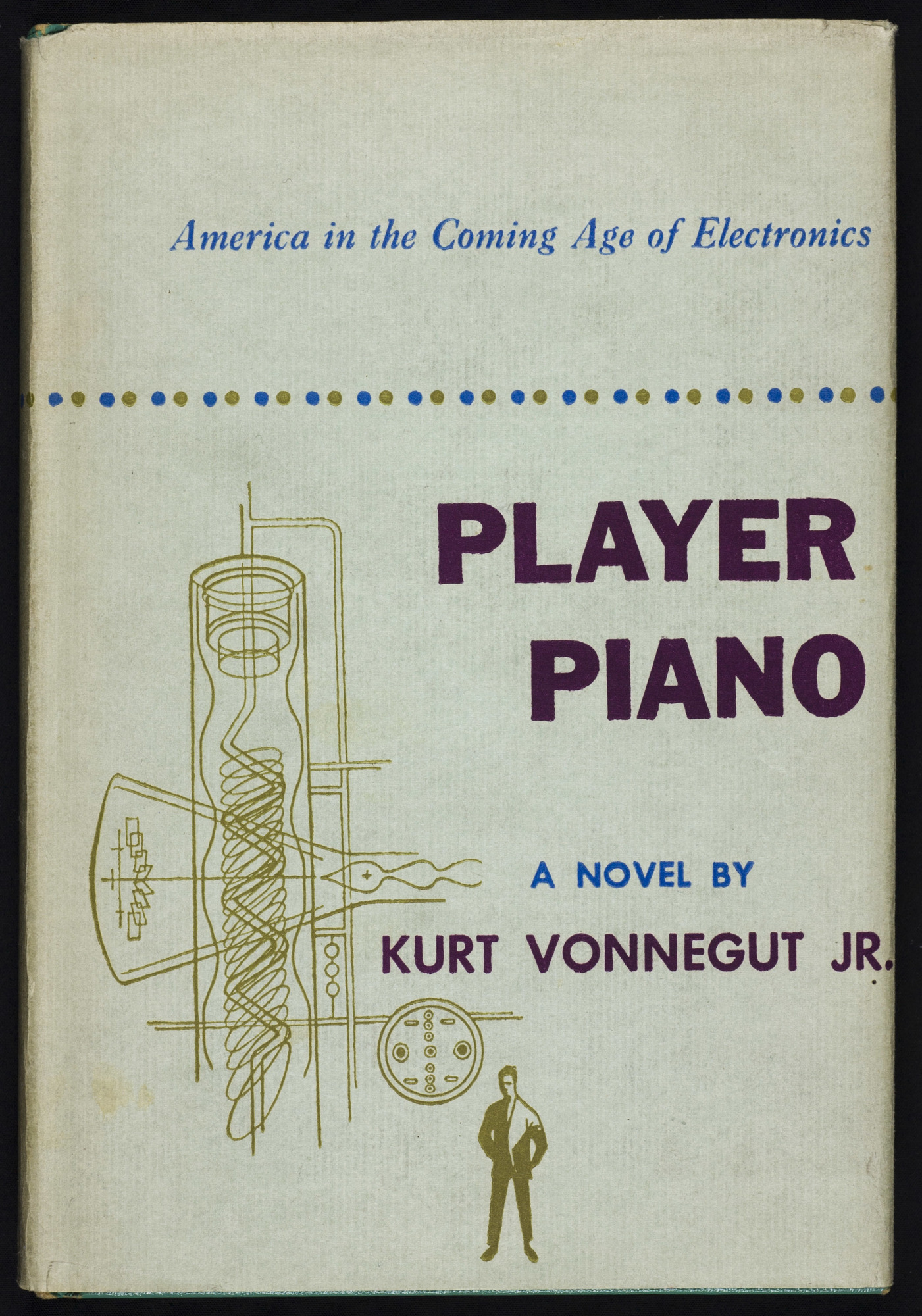

Kurt Vonnegut, Player Piano. New York: Scribner’s 1952.

Based on Vonnegut’s experiences as a publicity writer for General Electric, his first novel offers a vigorous critique of a society that leaves its future entirely in the hands of the engineers. A group of rebels against the future of a mechanized United States is the Ghost Shirt Society, a name obviously influenced by Vonnegut’s thesis work. Taking their cue from the Native American ghost dancers, the founders of the Ghost Shirt Society are committed to fight for the “old values.”

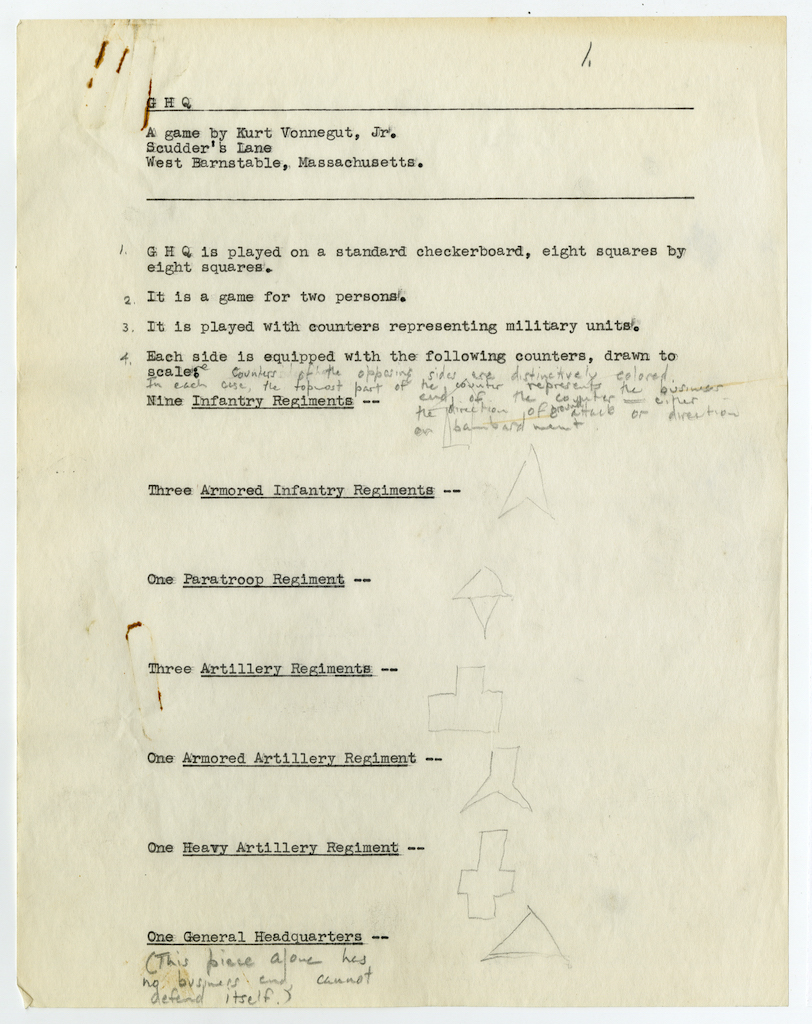

Kurt Vonnegut, GHQ game. Typescript, 1956.

A game for two players developed by Vonnegut himself. The two players move military units against each other with the aim of destroying the opposing GHQ (“General Headquarters”). Only one unit may occupy a given square at a time. Vonnegut’s instructions covered textbook tactical situations. The accompanying correspondence shows his efforts to market the game, which, he claims, “works like a dollar watch.” A nine-year old could learn it, added Vonnegut in his letter to Henry Saalfield, of the Saalfield Company, November 14, 1956. Saalfield rejected it.

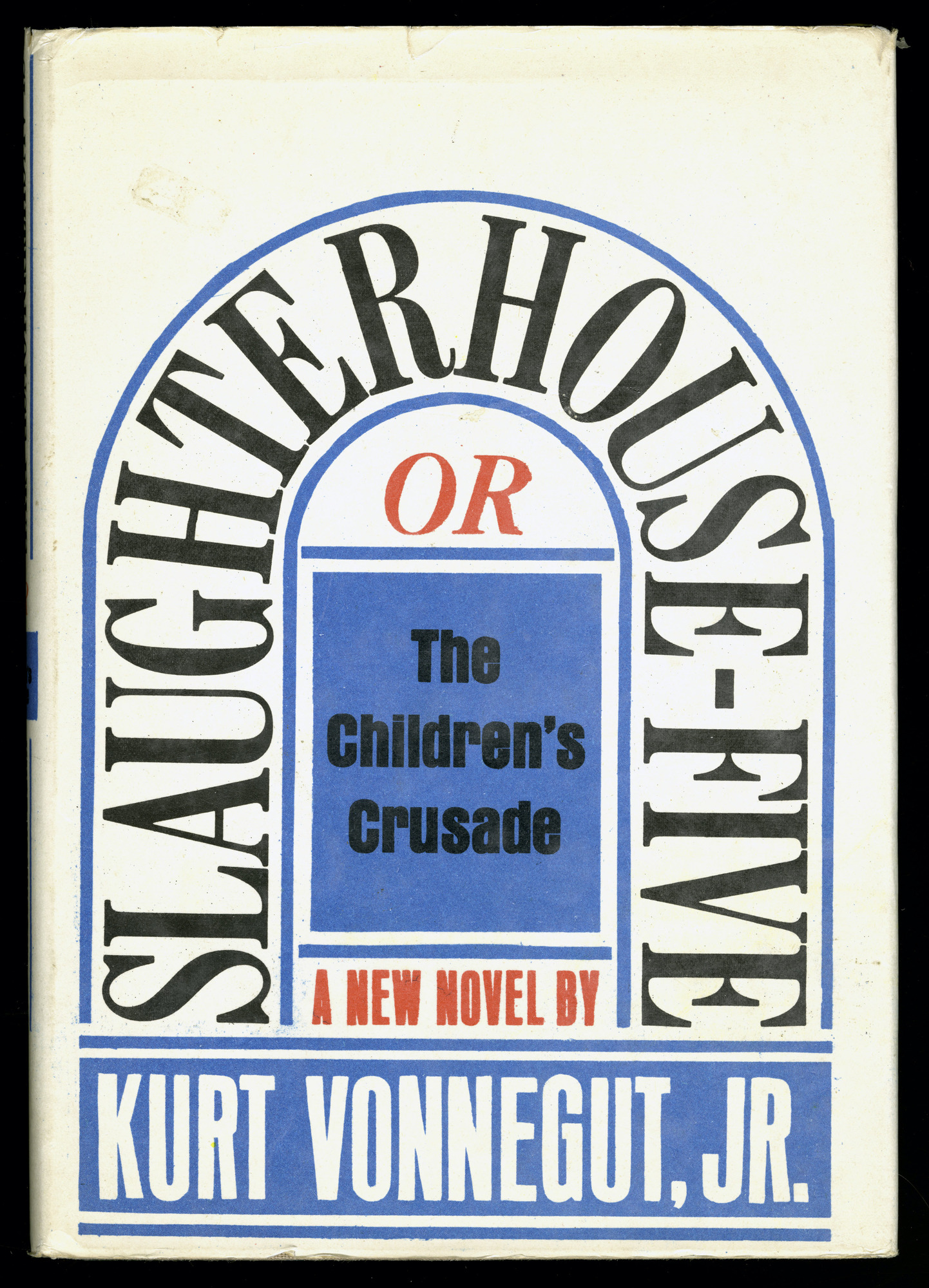

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade, a Duty-Dance with Death. [Taipei]: [Chin san], [1969].

The novel, published in 1969, resonated with a generation of Americans disenchanted with the Vietnam war and made Vonnegut an instant cult figure, not just in the U.S. but elsewhere, as this pirated copy proves. His novel, said critic Leslie Fiedler, was “less about Dresden than about Vonnegut’s failure to come to terms with it,” a failure that translated into so many challenges to literary convention that critics were unsure how to classify it: was Billy Pilgrim, the optometrist student drafted into a war that would change his life as it did Vonnegut’s, the novel’s hero or even a literary character? The extraterrestrials who abduct Billy and provide him with a mate, this redeeming him from the PST caused by his experience of the Dresden bombing, are creatures produced by his overactive brain. And yet the healing they bring is real, as it certainly was for the novels creator: “I felt that after I finished Slaughterhouse-Five that I didn’t have to write at all anymore if I didn’t want to.”

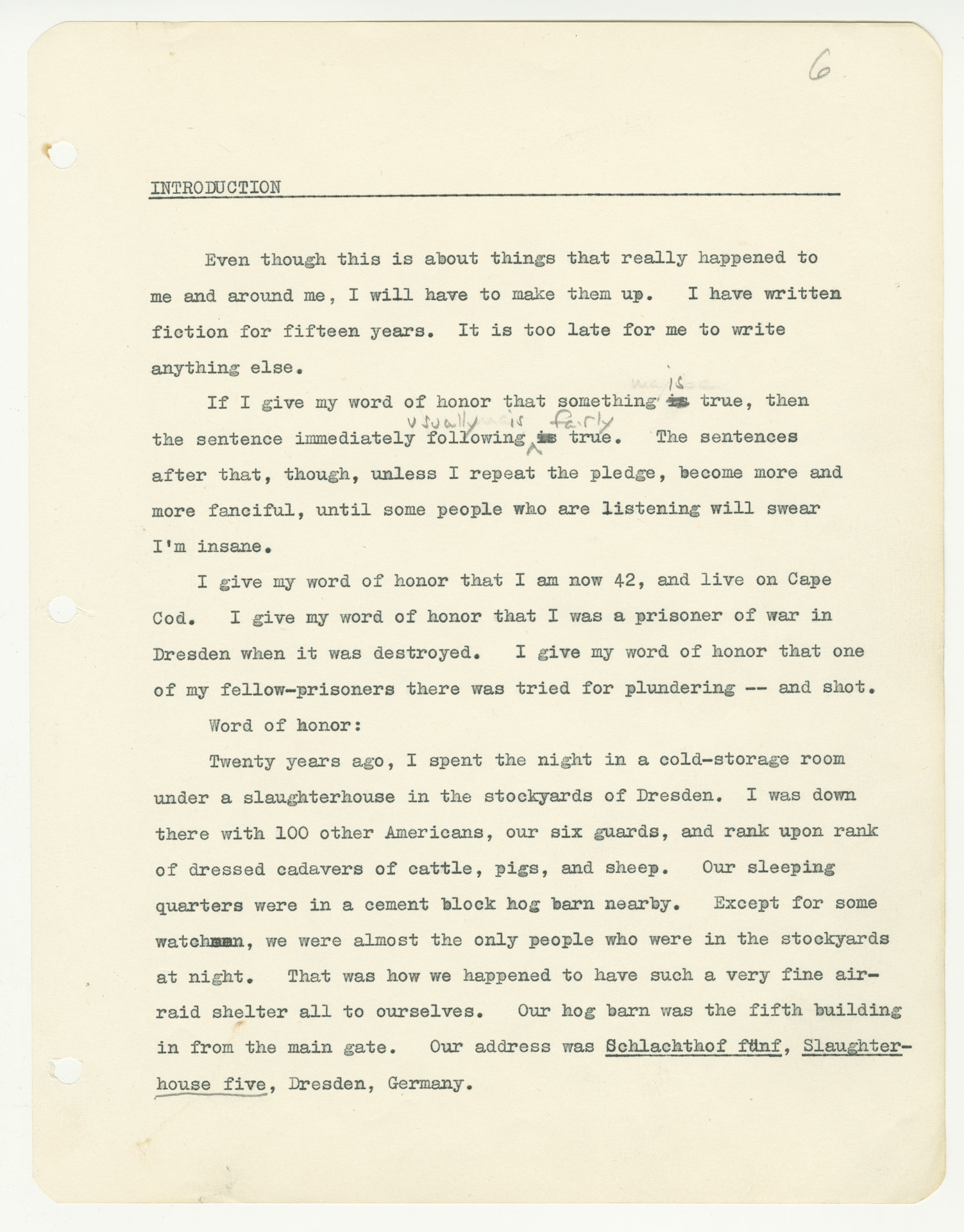

Kurt Vonnegut, drafts for the beginning of Slaughterhouse-Five: “I live on Cape Cod” and “Even though this is…”

Slaughterhouse-Five required more revising than any of Vonnegut’s previous novels. Shown are two discarded, wrenchingly personal versions of the novel’s beginning. The rawness of Vonnegut’s emotion is evident in both drafts. Consider the phrase “word of honor,” repeated three times, in “Introduction” and the studied casualness with which he refers to the victims of the Dresden bombing (“a cool one-hundred and thirty-five grand”) in the untitled draft. While the final version of the beginning seems more controlled (“All this happened, more or less”), the intensity remained.

Unknown photographer, Kurt Vonnegut with Arthur Miller, Vaclav Havel, David Dinkins, Joe Papp, and Edward Albee. Photograph taken February 23, 1990.

Provided to Vonnegut by the office of the mayor of New York City. At a breakfast at Gracie Mansion, the newly elected Czech president and successful playwright Havel was joined by playwrights Miller and Albee and Wendy Wasserstein (not portrayed) as well as the theater producer Joe Papp.

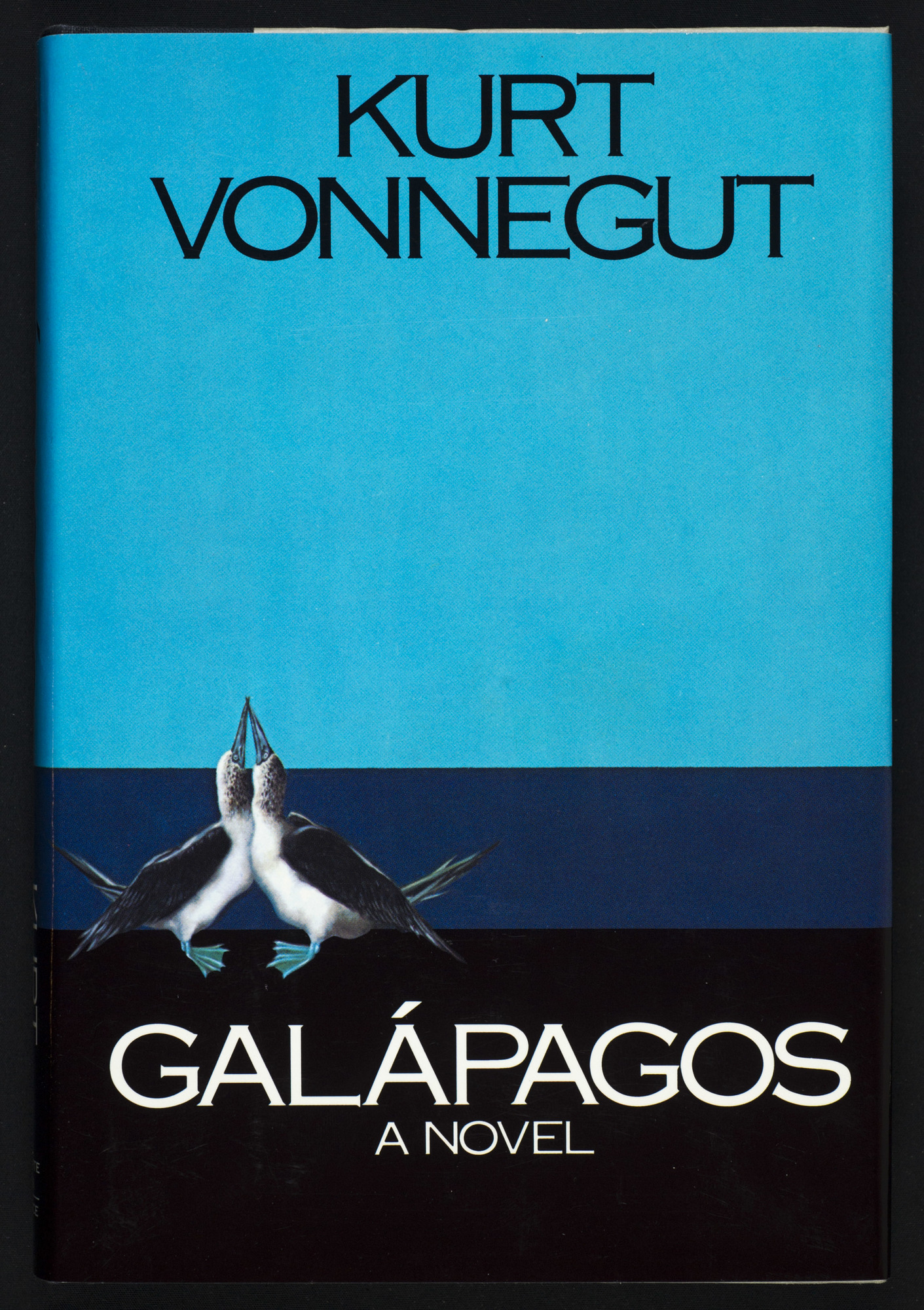

Kurt Vonnegut, Galápagos. New York: Delacorte, 1985, with promotional button issued by Delacorte, featuring blue-footed boobies.

A savage satire of the reverence for human progress, Vonnegut’s novel images what happens when the apocalypse takes place and the last surviving members of the human race, thanks to their big brains, devolve into seal-like animals with flippers for arms who devote their lives to eating and mating. Quoting Thoreau, Vonnegut states: “Nobody leads a life of quiet desperation now.” A high point in the novel is the dance of the Blue-Footed Boobies, in a film screened by Mary Hepburn, biology teacher from Ilium, who is about to leave for her Galápagos cruise: a dance for the sake of nothing but the fulfillment of biological need. At the end of the novel, Mary Hepburn is eaten by a shark, in the very location where Darwin had found evidence of evolution. Her degree in zoology was from Indiana University.

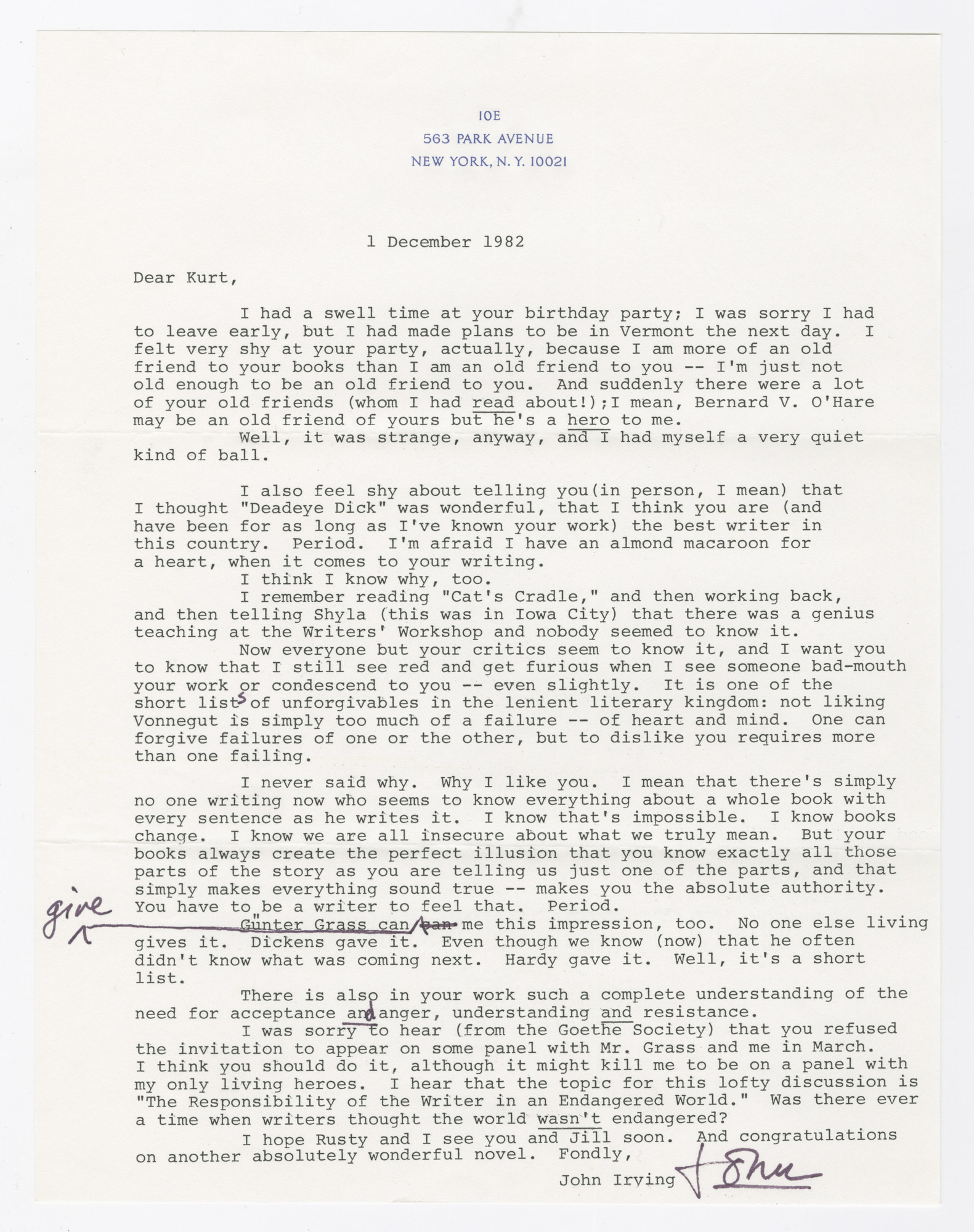

John Irving to Kurt Vonnegut, December 1, 1982.

“I think you are (and have been for as long as I have known your work) the best writer in this country.” Irving, famous for The World According to Garp (1978), The Cider House Rules (1985), and A Prayer for Owen Meany (1989) was Vonnegut’s student at the University of Iowa.