Theodore Dreiser

Born in 1871 in Terre Haute to German immigrant father and converted Mennonite mother. He attended Indiana University Bloomington from 1889-1890 before dropping out. After stints as a journalist in Chicago, St. Louis and Pittsburgh, he worked for his brother Paul Dreiser’s music publishing firm and eventually as a free-lance writer, producing novels such as Sister Carrie (1900) and Jennie Gerhardt (1902) that with their focus on the character-determining force of the environment strained the limits of bourgeois acceptability. After leaving his wife and dedicating himself to his own version of polyamory (he called it “varietism”), Dreiser enjoyed his first significant success with An American Tragedy (1928), a novel inspired by the 1906 murder of Grace Brown. As he was drifting into political activism, be became a staunch antifascist, advocate for labor rights and civil rights, as well as a supporter of communist Russia, joining the Communist Party five months before his death in Hollywood, California, on December 28, 1945.

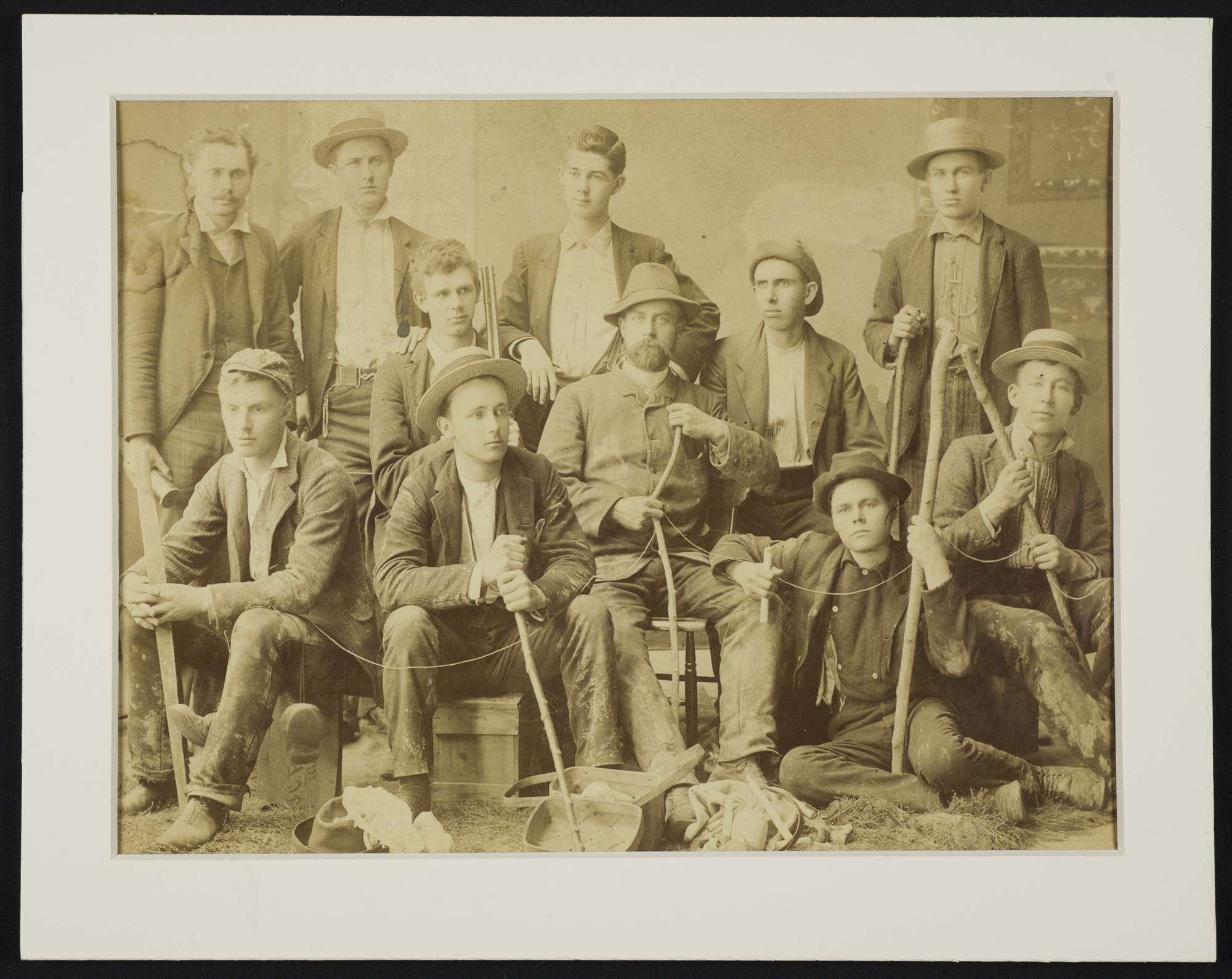

Unknown photographer, Dreiser with Indiana University Cavers, 1890.

In his autobiography, Dawn (1931), Dreiser mentions the caving expeditions organized by Indiana University’s geological department, which he joined at the advice of fellow student Russell Sutcliffe. “We had a glorious time listening to the instructive remarks of the geologist, feeling our way about narrow ledges and through body-tight openings which almost invariably gave into spacious chambers or passageways.” Dreiser remembered Sutcliffe as the “most intellectually sincere” of all the students he had met in college. His other close friend was Howard Hall, “an earnest, undersized, and meticulous law student,” and poor like Dreiser himself. A speech impediment made Howard’s success in the courtroom unlikely; as Dreiser noted, he would die at age 24, “the victim of a constitution not sufficiently robust to endure the raw forces of life.” Dreiser and Hall set out on a caving expedition on their own, with nearly disastrous results after they lost track of their string. In this photograph, Hall is second from the left in the front row and Sutcliffe rests his arm on the leg of Professor of Romance Languages Gustaf Karsten. Dreiser appears seated in the back row.

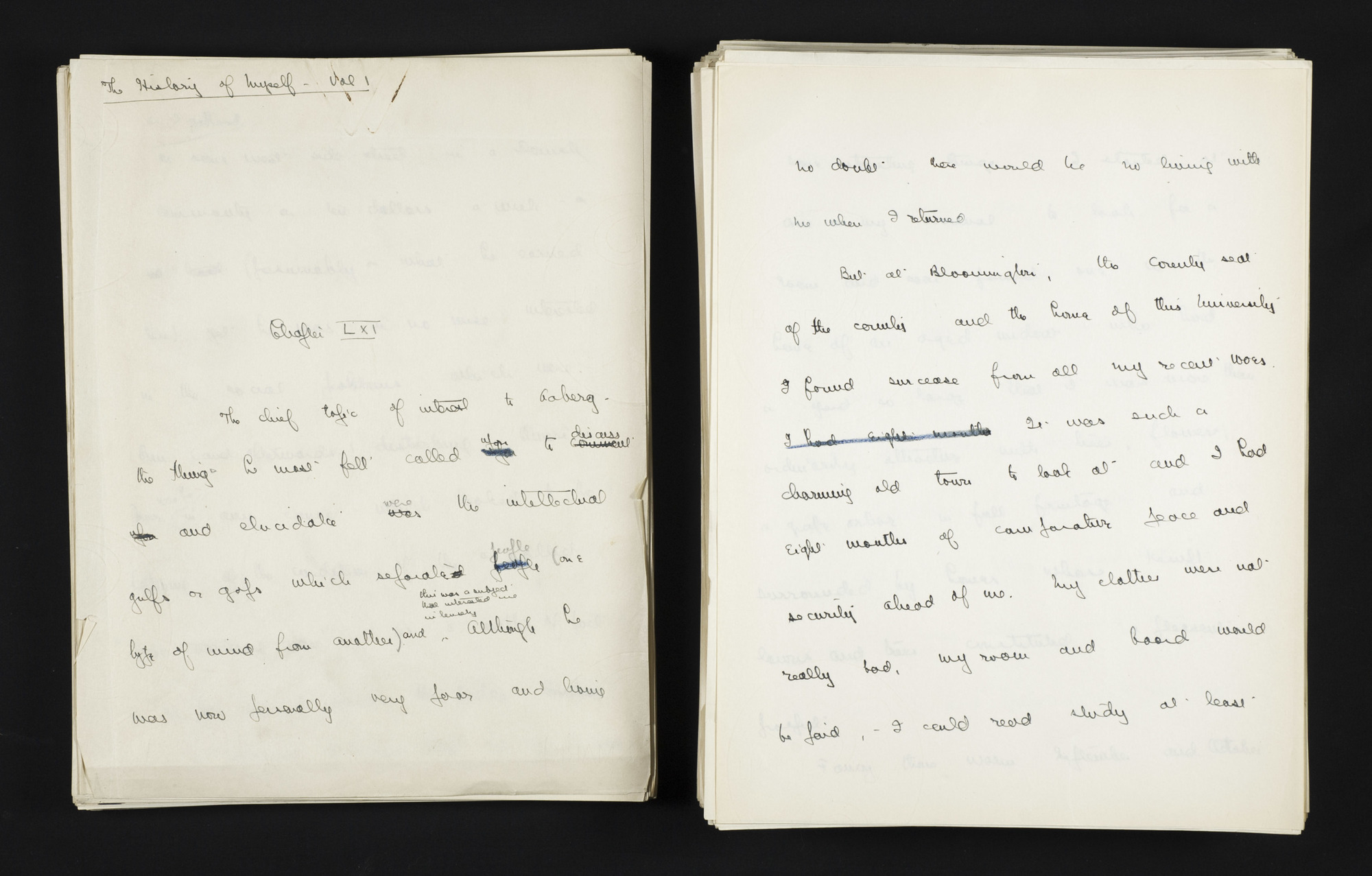

Theodore Dreiser, holograph manuscript of Dawn, completed 1916.

The manuscript of Dawn, titled “History of Myself,” comprises four boxes. Unsure if his readers were ready for the stark honesty of his self-portrait, especially regarding sexual matters, Dreiser locked the manuscript away and reassessed it after the success of An American Tragedy. As Dreiser remembers it, traveling from Chicago to Bloomington was “like coming into a still chamber and preparing to rest and sleep.” But that is not what in fact happened to him. Chapter 68, significantly edited in the published version, details his disastrous encounter with a Bloomington girl next door. When the girl, sensing Dreiser’s interest in her, came over to ask a grammar question, Dreiser panicked: “She began by opening the book and pointing to a sentence which she said she did not know how to parse. Which was the subject, which the predicate? What did something modify?” Instead of kissing her, as it would have been easy for anyone to do (or so Dreiser thought), he finds himself reduced to a babbling idiot. Of course, he loses the girl to William Levitt of Greenfield, Indiana.

Theodore Dreiser, Dawn. New York: Liveright, 1931.

With author’s inscription to Yvette Eastman, formerly Szekely (“Love, TD”). Dreiser met the Hungarian-born Yvette when her stepmother Margaret interviewed him in New York: the beginning of a long, problematic relationship Yvette recalled in her memoir Dearest Wilding (1998). At one of her mother’s dinner parties in early January 1931, Yvette also met the poet, critic, and activist Max Eastman, whom she eventually married in 1957. The Lilly Library’s extensive Max Eastman collection also contains Eastman’s personal copy of Dawn, profusely annotated by a jealous Max. Yvette, a generous donor to the Lilly Library, died in January 2014 on Martha’s Vineyard.

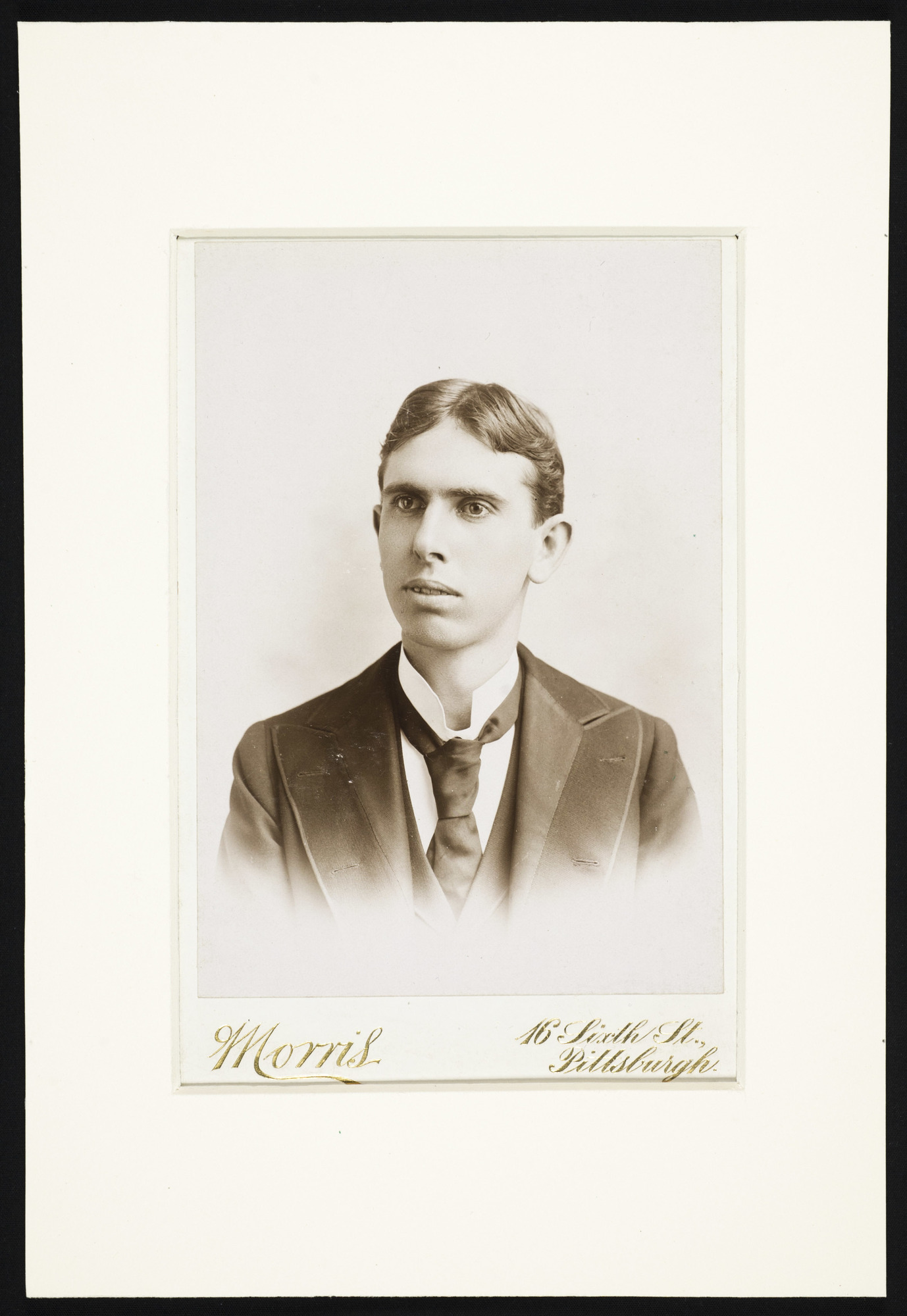

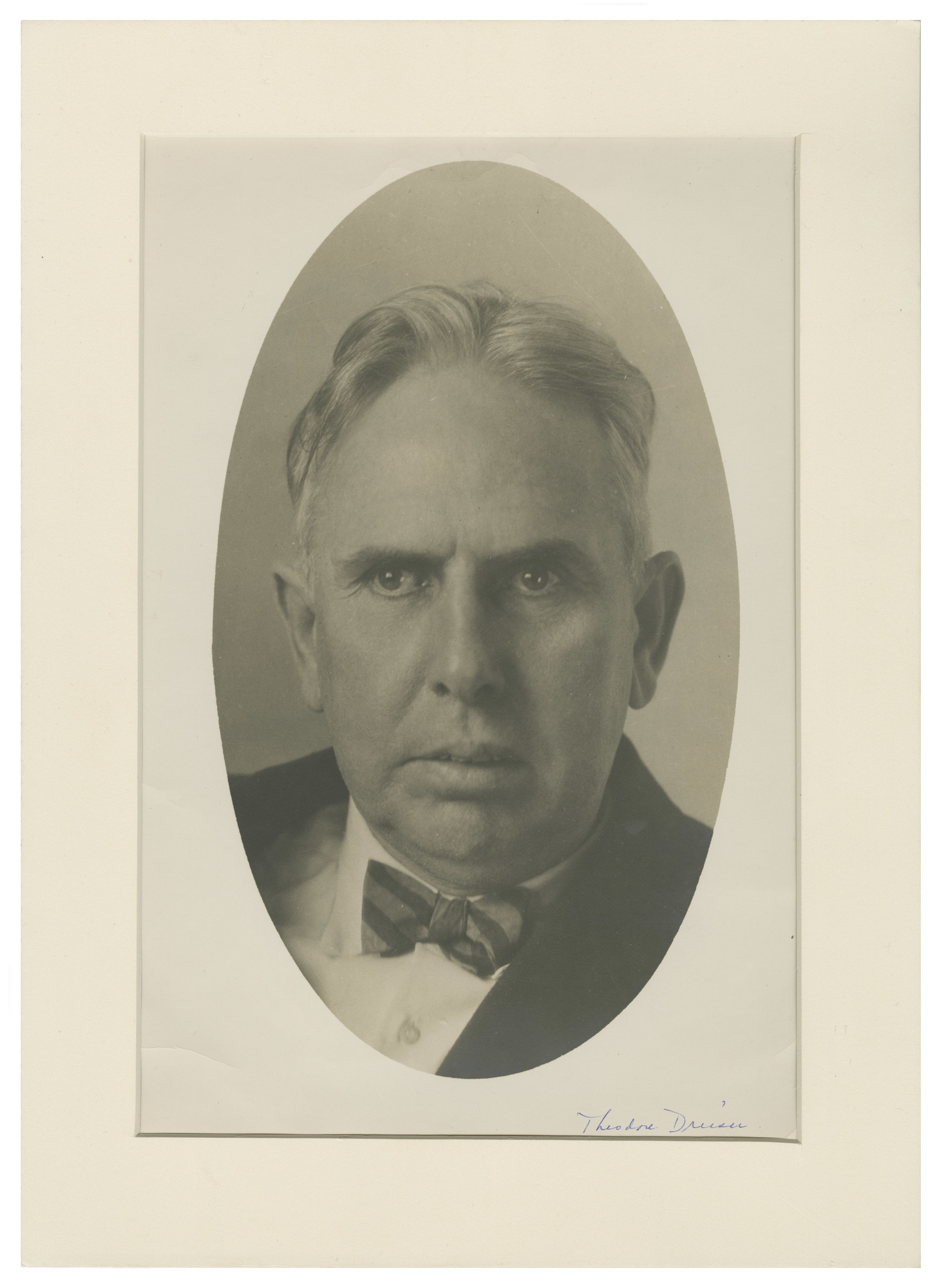

Studio of Joseph G. Morris, Theodore Dreiser, 1894.

Taken when Dreiser was about twenty-four. Morris maintained a studio in Pittsburgh at 16th Sixth Street.

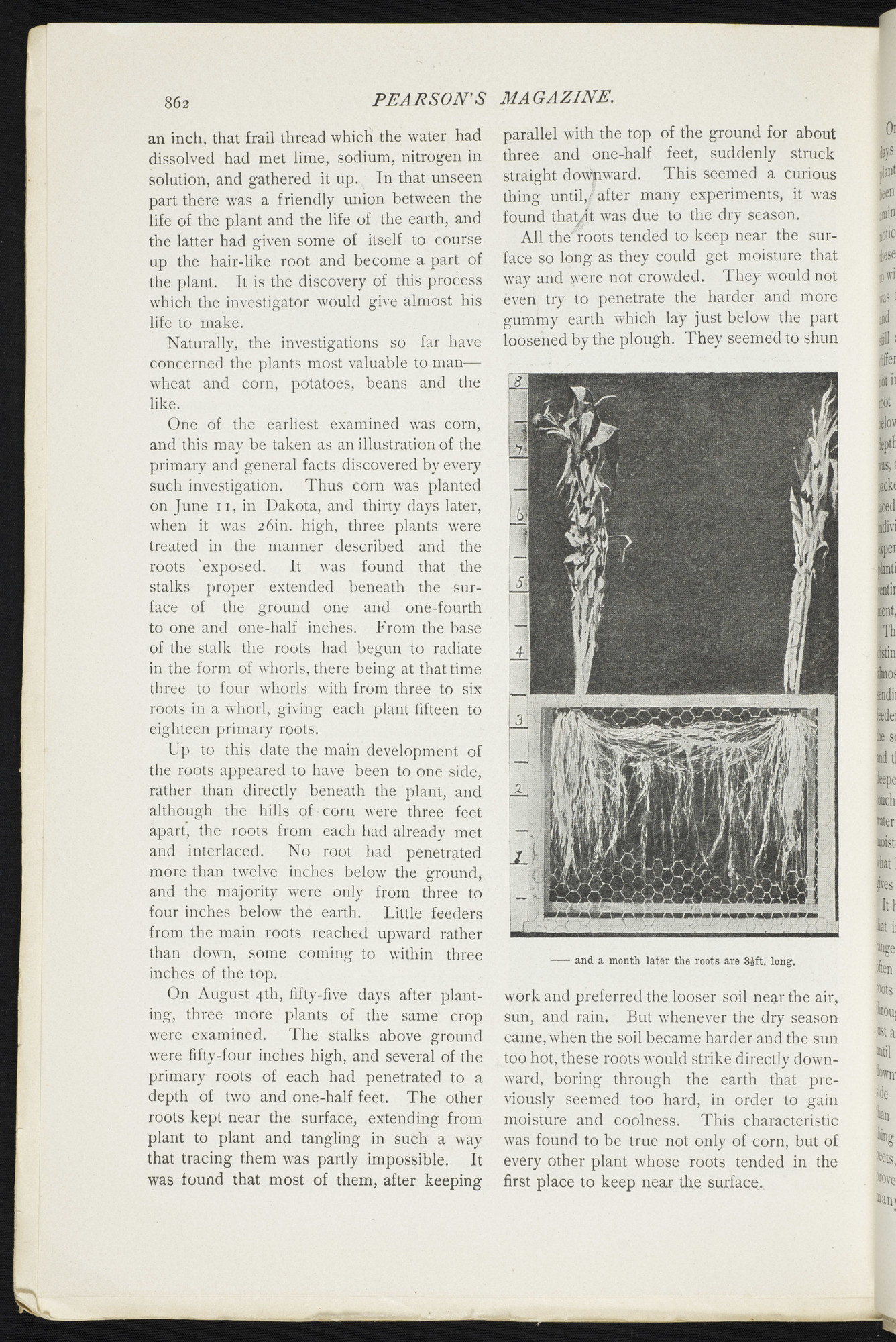

Theodore Dreiser, “Plant Life Underground: The Importance of the Scientific Discovery of Plant Roots, and the Remarkable Discoveries About Plant Life and Growth to Which This Study Has Already Led,” Pearson’s Magazine, June 1901.

In this somewhat unusual entry, Dreiser summarizes experiments on the behavior of roots conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in South Dakota. In line with his own investigations into the role environment plays in the lives of literary characters, he takes pleasure in the observation that no plants should be deprived, “for lack of ample ploughing,” in its search for the chemicals it needs. And in line with his Hoosier origins, the primary example he chooses is the corn plant.

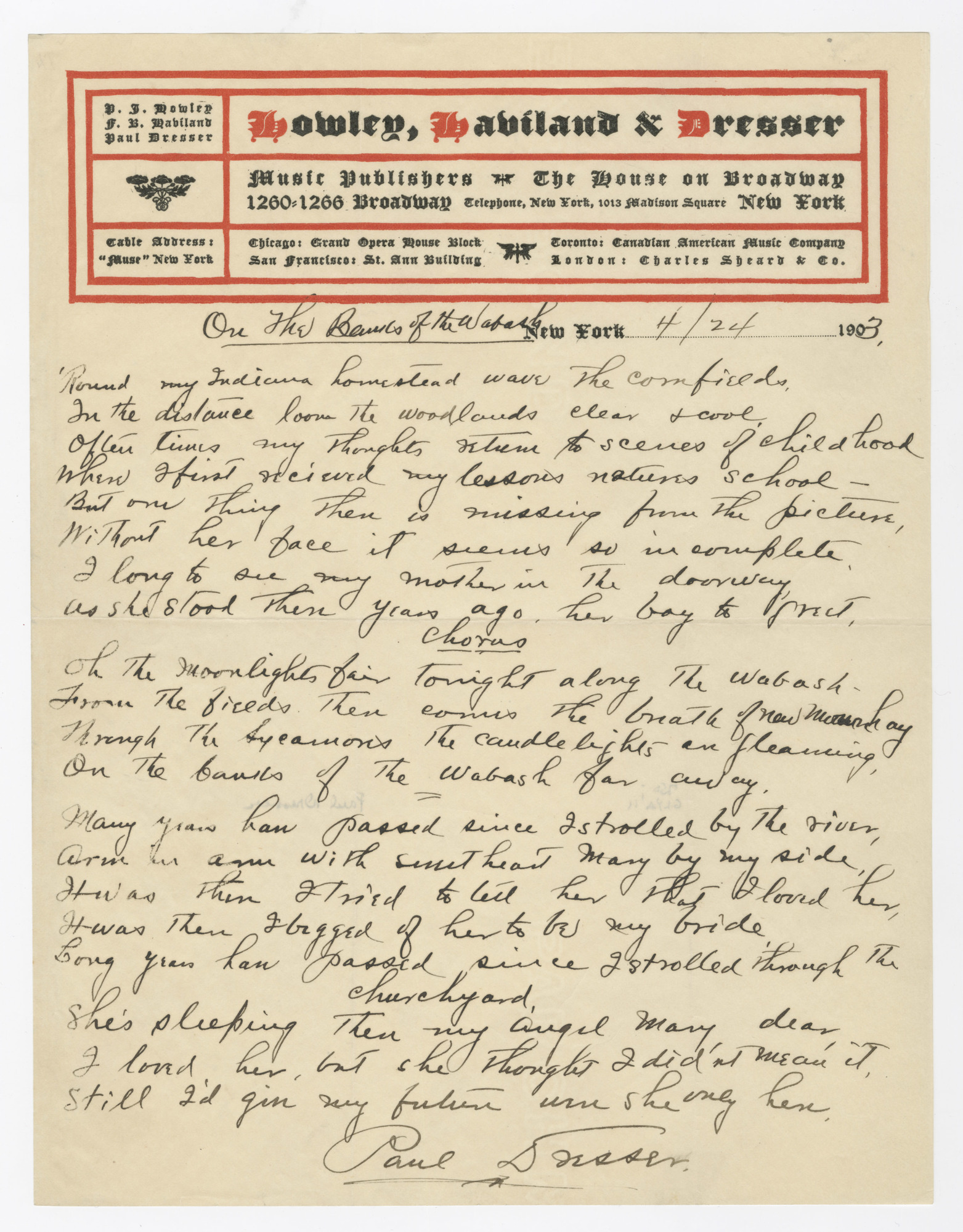

Paul Dreiser, holograph manuscript of “On the Banks of the Wabash River, Far Away.”

Born Johann Paul Dreiser on April 22, 1858 in Terre Haute, Theodore Dreiser’s older brother rebelled against the family’s wish that he become a priest, changed his last name, and embarked on a wild life as an itinerant musician and vaudeville performer. Although he had never received any formal musical training, he eventually became the nation’s most famous composer. Among his more than 150 songs are such hits as “We Were Sweethearts for Many Years” (1895) and “Lost, Strayed or Stolen” (1896). “On the Banks of the Wabash River” became the second-bestselling song of the nineteenth century. In 1913 it was adopted as the official state song by the Indiana General Assembly. No wonder his younger brother Theodore would later claim to have written half of it. Generous to a fault, Dreiser gave much of his vast income away and died penniless. His grave remained unmarked until 1922.

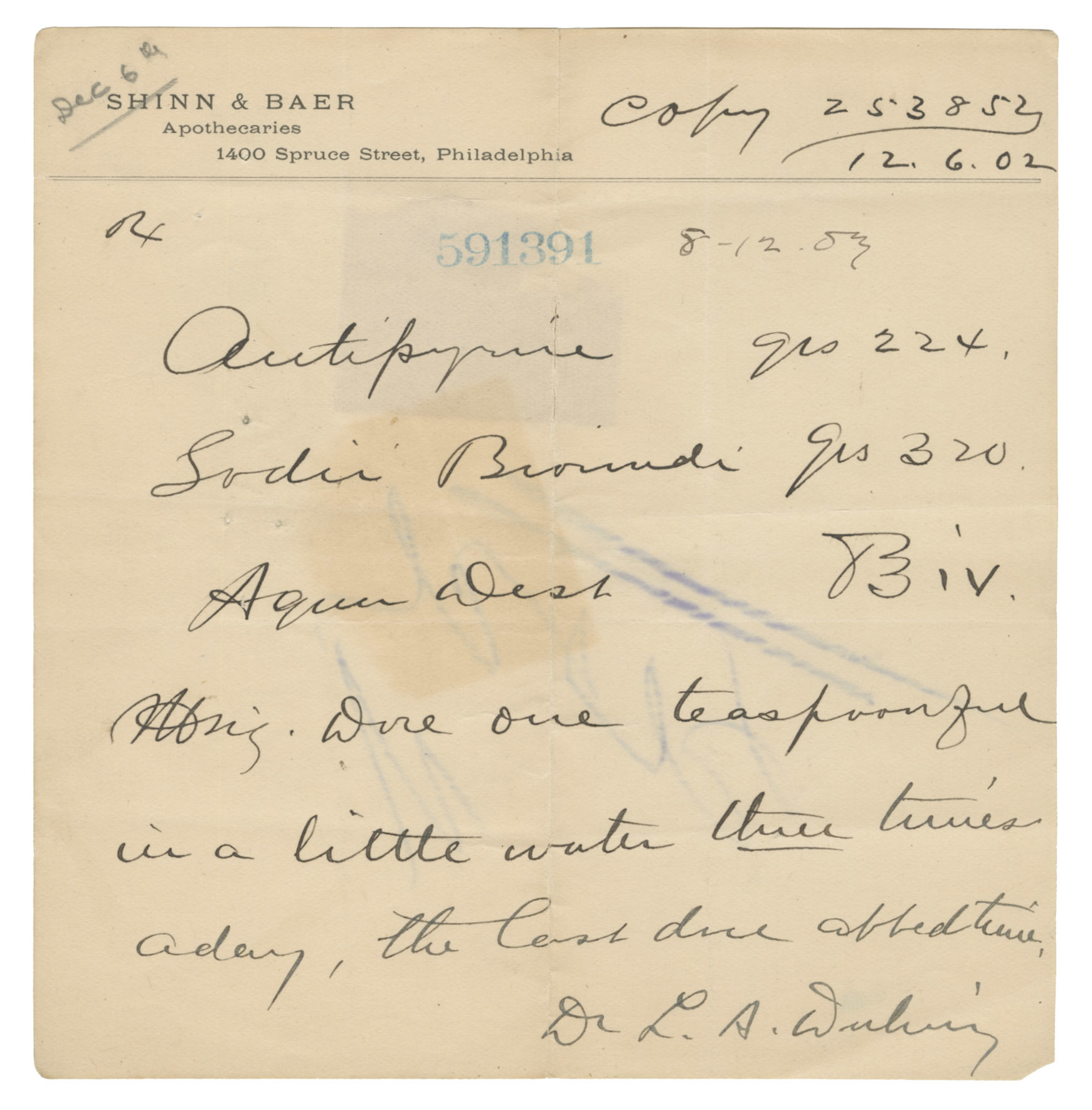

Theodore Dreiser, prescription note, December 6, 1902.

Prescription, written and signed by the Philadelphia dermatologist Dr. Duhring, for the painkiller “Antipyrine” and other remedies, to be taken “one teaspoonful in a little water three times aday [sic], the last one at bedtime.” Stung by the lack of enthusiasm among publishers for Sister Carrie, Dreiser had taken refuge in drugs. Donated by David Randall, first director of the Lilly Library.

Charles Sheeler, Theodore Dreiser, 1933.

The modernist painter Charles Sheeler took several portraits of Dreiser, first in 1926, and then again in 1933. Both times, the results appeared in Vanity Fair.

Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie. New York: Doubleday, 1900.

Sister Carrie describes the rise to fame of an innocent-seeming girl, Carrie Meeber from Columbia City in Wisconsin. Her path to success in the New York theatre world is littered with the bodies of the men who became infatuated with her. After Harper and Brothers objected to his “reportorial realism,” novelist Frank Norris, who worked for Doubleday, Page & Co, ensured that the novel would be published under the Doubleday imprint. But Frank Doubleday, once he had become aware of Dreiser’s immoralism, tried to suppress the edition and, when that proved legally impossible, required drastic edits. The mutilated book, published in November 1900, gathered few positive reviews. An unexpurgated version of the novel would not be published until 1981.

Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie. New York: Modern Library, 1917.

This copy belonged to poet Sylvia Plath, who read Sister Carrie in 1955, as a fully entitled undergraduate student at Smith College, free to express her dislike for Dreiser’s narrative intrusions: “Dreiser elaborates & orates.”

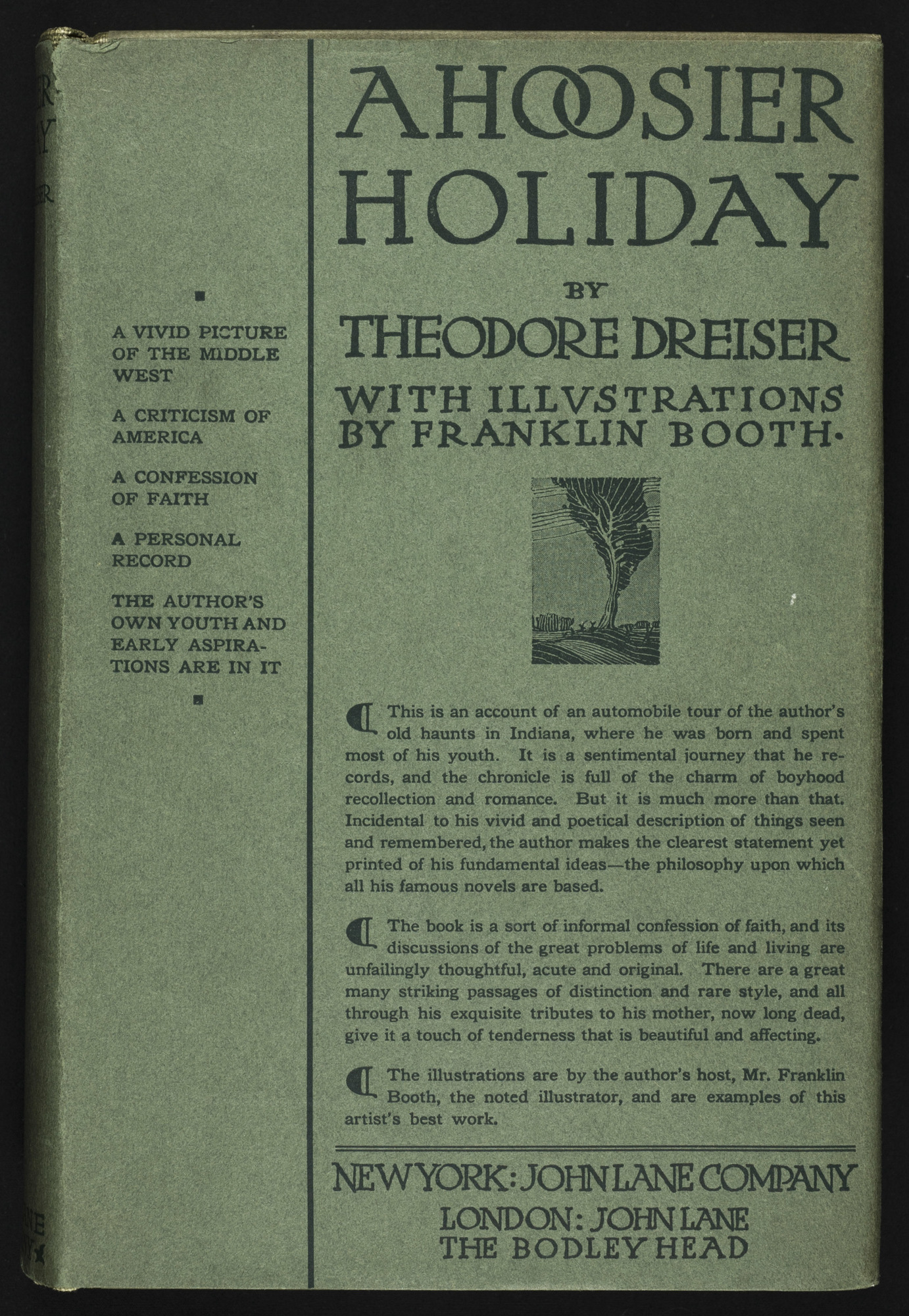

Theodore Dreiser. A Hoosier Holiday. New York: John Lane, 1916.

In 1915, Hoosier illustrator Franklin Booth, proud owner of a new Pathfinder Roadster, proposed a tour of the state to Dreiser. In 1915, the two men, accompanied by a mechanic and a driver, drove some 2,000 miles revisiting places associated with Dreiser’s youth, among them Bloomington, Carmel, Evansville, and Terra Haute. Booth sketched and Dreiser wrote, often waxing melancholy about the alterations of the landscapes he remembered from his childhood. While his enthusiasm for Indiana was measured, Dreiser’s embrace of the new means of transportation is unequivocal: “I could go motoring on and on.” The manuscript he produced after the trip ran to some 250,000 words. A Hoosier Holiday was published in November 1916, perhaps the first incarnation of the genre of the American road book.

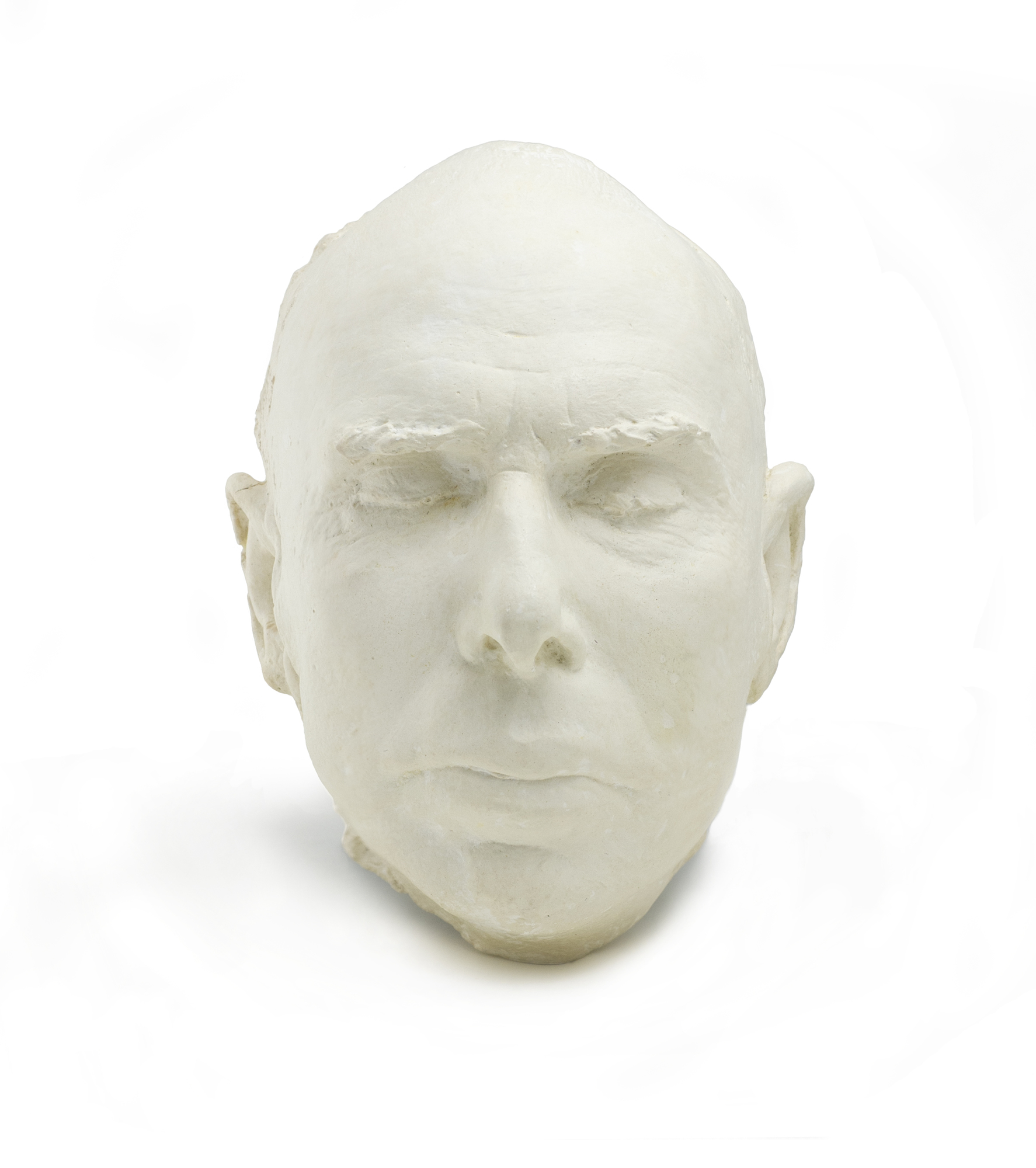

Edgardo Simone, Theodore Dreiser’s death mask, 1945.

Donated by Vera Dreiser (1908-1998), Theodore Dreiser’s niece, a dancer and psychologist, who interviewed the women involved in the Charles Manson murders. Edgardo Simone (1890-1958) was an Italian sculptor who emigrated to the United States and worked in various genres, including portraits and monuments.

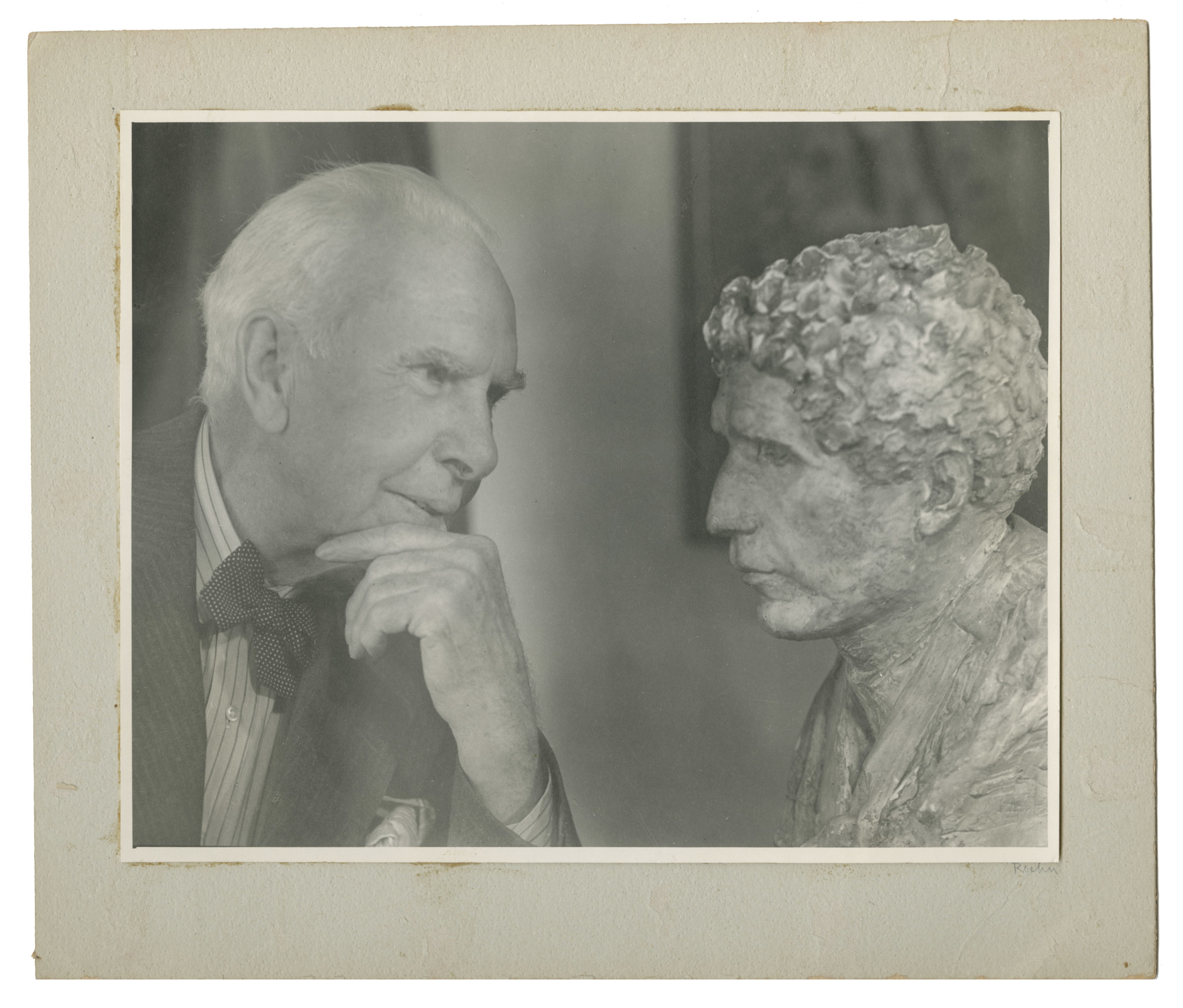

Unknown photographer, Theodore Dreiser with Bust of John Cowper Powys, California, 1942.

John Cowper Powys (1872-1963), a self-declared anarchist and committed eccentric, was the author of lengthy novels (Wolf Solent, 1928; A Glastonbury Romance, 1932) as well as of an autobiography (1934) that attracted Dreiser’s attention, since the author therein described himself, with the kind of self-deprecation familiar to Dreiser from his own efforts in the genre, as a “scarecrow Don Quixote with the faint heart of Sancho.” Powys (or “Jack,” as Dreiser affectionately called him) and Dreiser had met in Greenwich Village in 1912. His bust was in Dreiser’s possession.