Beginnings

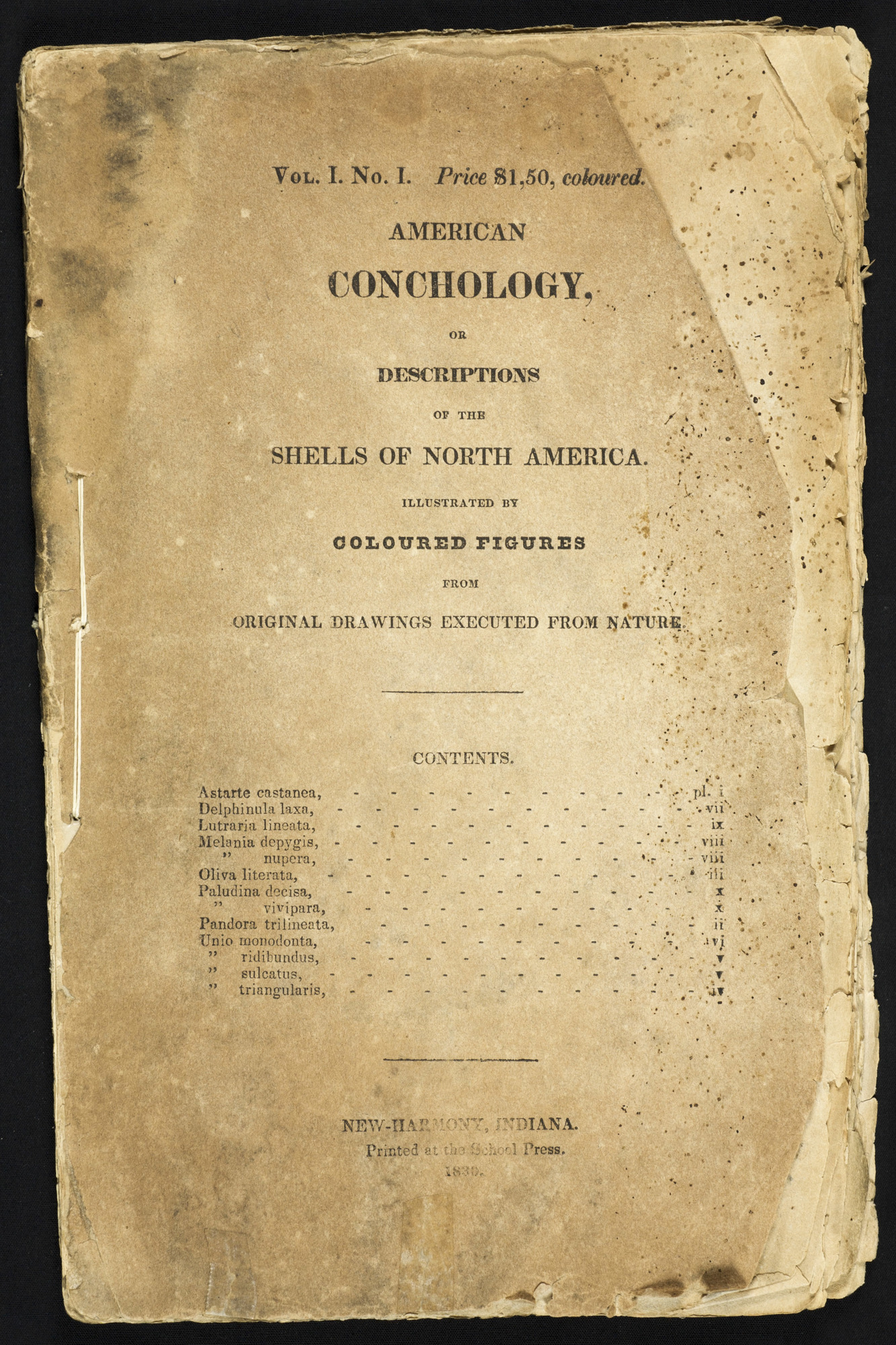

Thomas Say, American Conchology, or, Descriptions of the Shells of North America. Part 1. New Harmony, Indiana: The School Press, 1836.

The naturalist Thomas Say (1787-1834), professor of natural history at the University of Pennsylvania and librarian at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, led the “boatload of knowledge,” the group of scientists that joined Robert Owen’s communitarian experiment at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1823. His comprehensive work on American shells was illustrated by his wife, Lucy Say, who completed the work after her husband’s untimely death. Say’s beautiful prose—for example, he writes about the “perlaceous color” of the shell featured in this plate, a specimen of “Unio Monondata” found in the Wabash River—makes his handbook one of the first and finest examples of the Hoosier literary tradition.

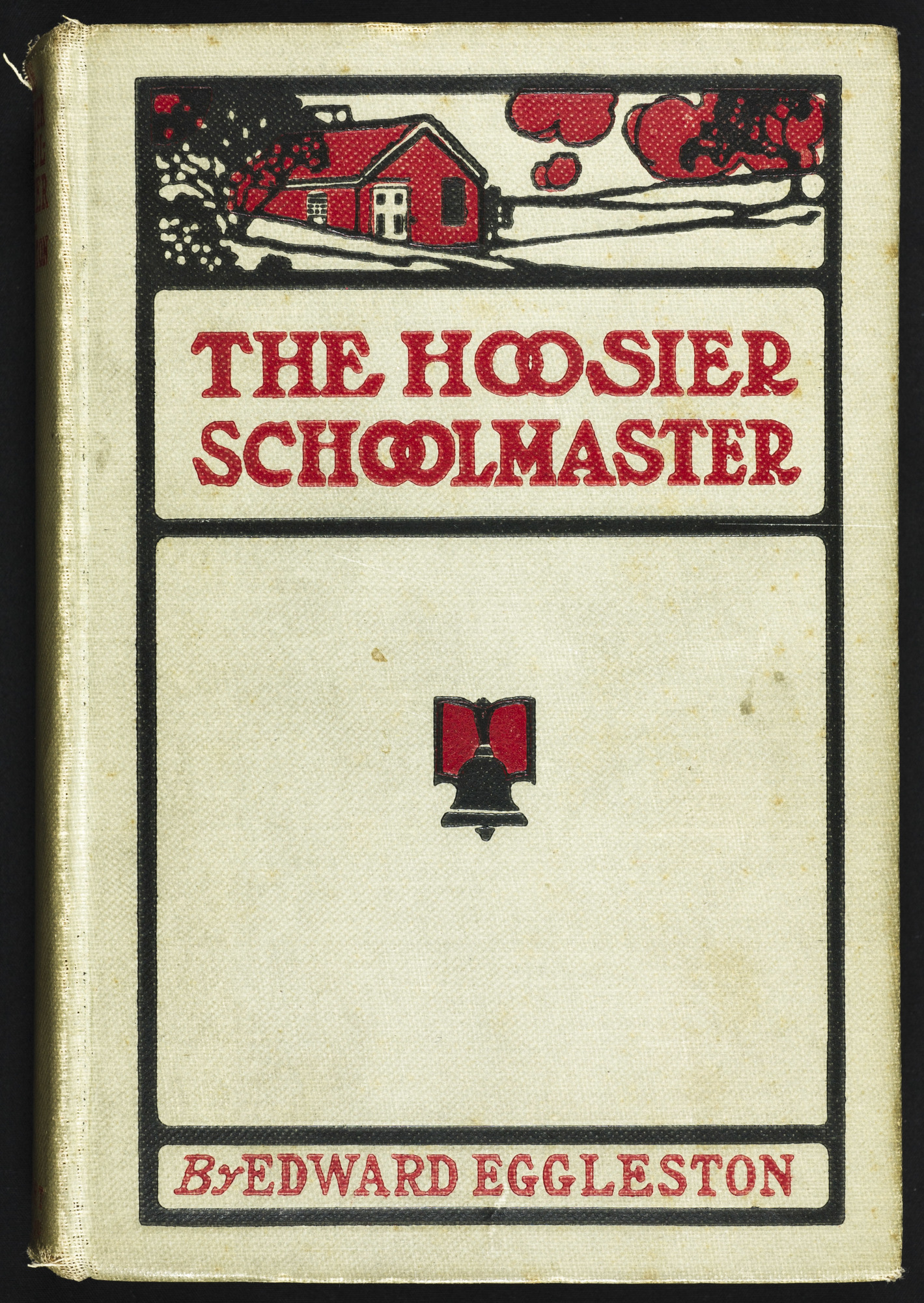

William Eggleston, The Hoosier Schoolmaster: A Story of Backwoods Life in Indiana. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1913.

The first Hoosier bestseller, published 1871. Eggleston modeled his novel on the experiences of his brother and fellow writer, George Cary Eggleston. Written to appeal to a broad readership, The Hoosier Schoolmaster contains a little something for every reader, from a puppy hidden in the teacher’s desk to the attempted “ducking” of the schoolmaster, who anticipates the prank and tricks the perpetrator instead, so that he falls into the ice-cold water beneath the schoolhouse. Pirated in England and translated into French, German, Danish and other languages, the book was still selling at a fast clip thirty years after its initial publication. This was J. K. Lilly’s personal copy of a later edition, with illustrations by W.E. Starkweather and “character sketches” by the Ohio-born cartoonist Frederick Burr Opper.

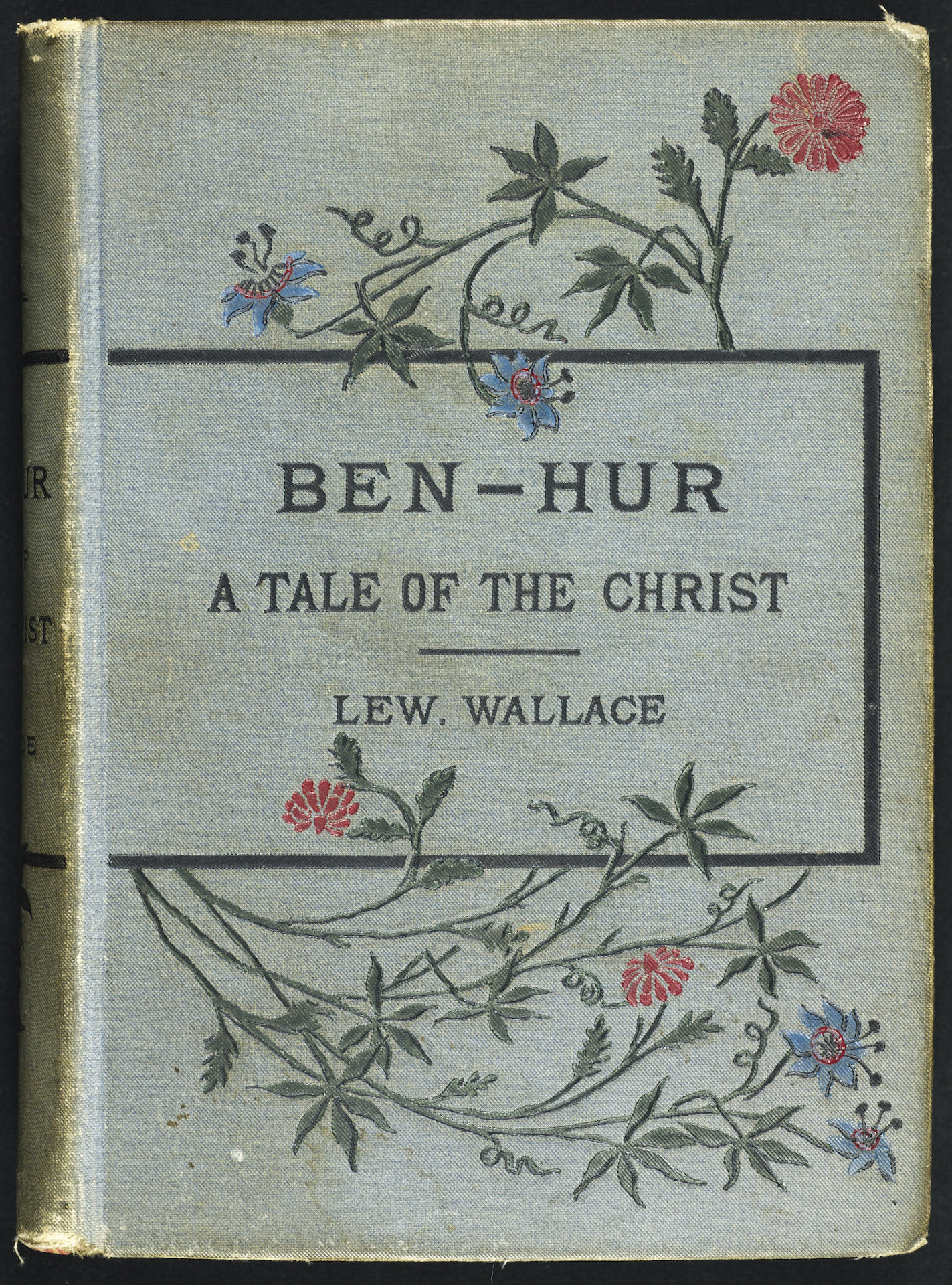

Lew Wallace, Ben-Hur, or, A Tale of the Christ. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880.

The novel originated in a discussion on a night train to Indianapolis between Wallace (1827-1905), an ex-Civil War general of doubtful distinction, and Robert G. Ingersoll, the nation’s most prominent atheist. (Ingersoll would later deliver the eulogy at Walt Whitman’s funeral.) Realizing that he knew less about his religion than he should, Lew Wallace committed to writing a novel about the origins of Christianity. It took him four years to tell the story of Judah Ben-Hur, a fictional prince from Jerusalem who is enslaved by the Romans and, converted by his encounter with Jesus, becomes a Christian. This copy carries a dedication to Mr. and Mrs. Ripley, “with the compliments of their friends—Lew Wallace and S.E. Wallace.” Wallace’s wife, Susan Ellston Wallace (1830-1907), was a prolific travel writer and poet.

Lew Wallace, Ben-Hur, or A Tale of the Christ. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880.

Wallace began writing Ben-Hur in Indiana and finished it in Santa Fe, where he served as Governor of the New Mexico Territory. The novel became the major bestseller of the second half of the 19th century, surpassing even Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ben-Hur was blessed by Pope Leo XIII, the first book of fiction that earned that distinction. This copy, in the alternate drab cover, was in the library of Indiana University President Herman B Wells.

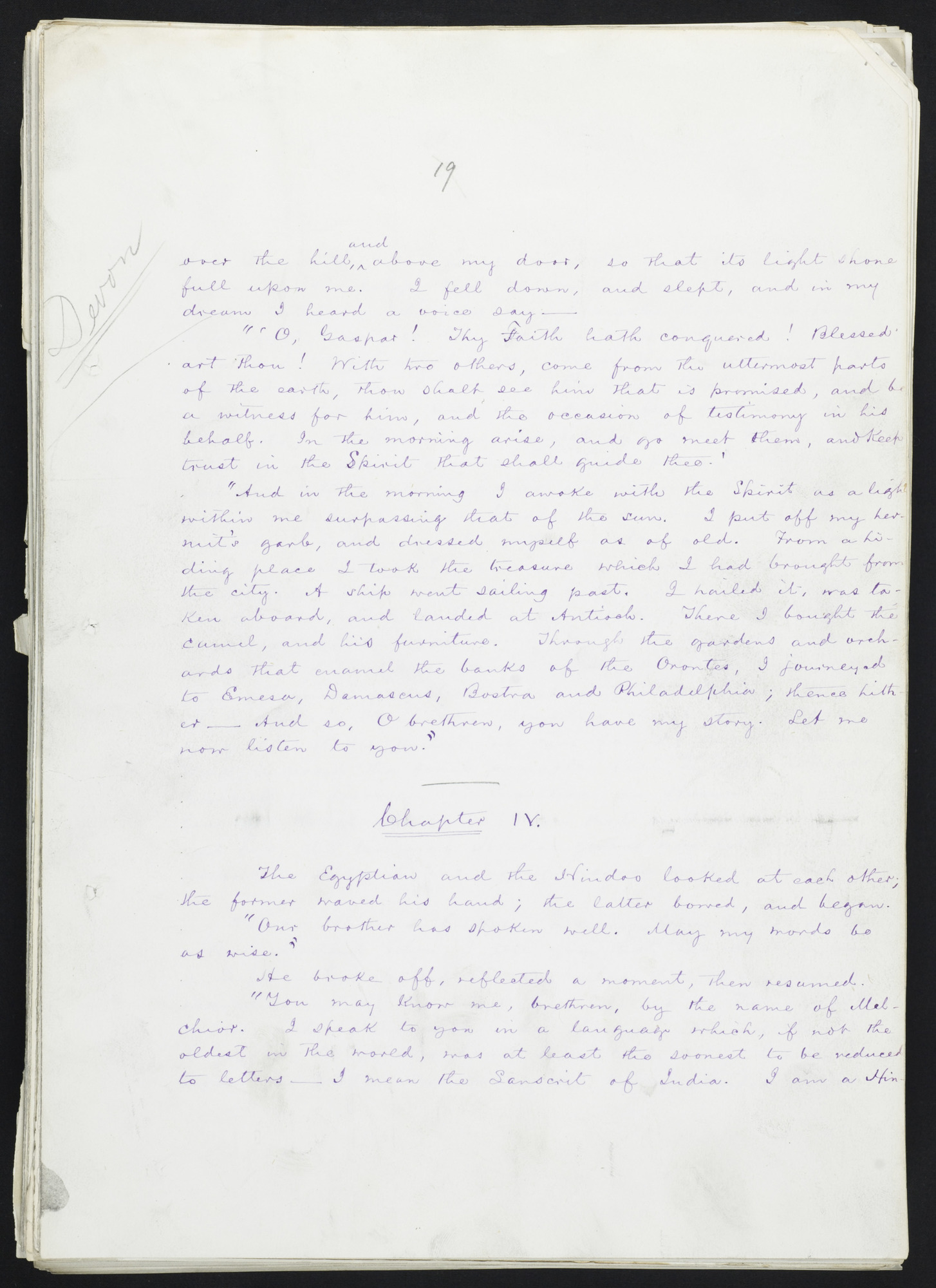

Lew Wallace, holograph manuscript for Ben-Hur, 1876-1880.

Wallace’s purple ink was intended to reflect the color of Lent, an indication of the profound spiritual awakening the author experienced as he was composing the novel. On display is the end of chapter 3, where Gaspar, one of the Three Magi, also known as “the Greek,” recalls the voice that told him to follow the star that would guide him to Jesus. The name in the margin (“Devon”) is that of the printer working for Harper’s. Each printer would “sign in” when beginning their portion of the typesetting work.