Hidden Color: Kodacolor Film in the Richard G. Lugar Home Movie Collection

Guest post by Alicia Hickman, Assistant Film Archivist at the IU Libraries Moving Image Archive (IULMIA)

In November 2018, all of the reels of film in the Richard G. Lugar Senatorial Papers collection at Indiana University Bloomington were processed and sent to be digitized through the Media Digitization Preservation Initiative (MDPI) at the Indiana University Bloomington campus. The collection includes a total of 161 reels of film. A large portion of these reels contain home movies captured by the Lugar family from the late 1920s to the mid-1950s. I was fortunate enough to work with some of these films in my capacity as Assistant Film Archivist with the IU Libraries Moving Image Archive (IULMIA), by inspecting and repairing the films as well as scanning them for digitization.

Through close inspection of the physical objects, I made an interesting discovery. The home movies in this collection range from 5-minute-long early films from the late 1920s and early 1930s to larger compiled reels of multiple Kodachrome color films shot in the 1950s. Within this earlier group of films, there are a few black and white home movies, many of which feature a very young Richard Lugar playing in his childhood home, filmed by his mother and father.

But not all black and white film is as it seems. . .

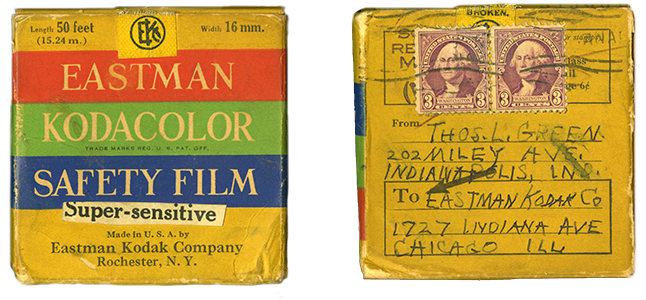

A handful of these earlier films shot by Senator Lugar’s parents, Marvin and Bertha Lugar, were not filmed on black and white film stock at all. Instead, they are examples of the unusual and short-lived Kodak color film stock known as KODACOLOR. Through MDPI, almost 10,000 films have been digitized and, so far, the Lugar film collection is the only collection we have worked with that contains Kodacolor films.

Kodacolor home movie of a thirteen-month-old Richard Lugar taking

some ambitious early steps, supported both by a baby walker and by family

members, including his father, Marvin Lugar. Using the available equipment,

this film has been digitized in its black and white form. However, it remains

possible to project the film in color given the proper projector setup.

In 1923, the Keller-Dorian-Berthon additive color process for 16mm film was successfully demonstrated in Paris. By 1928, the Eastman Kodak Co. put the process to practical use, creating a stable film stock that could carry color information.¹ The new film stock was released for amateur use in July of that year during a garden party hosted by George Eastman and attended by Thomas Edison. Kodacolor footage of the event shows Eastman using a Ciné-Kodak camera to film the party-goers.

Kodacolor film was very unique in the way that it captured color. Rather than using dyes, Kodacolor film used a three-color additive process that featured vertical lenticules – or, in other words, very tiny lenses – that were embossed into the microscopically-thin emulsion side of the film. The film was loaded into a Ciné-Kodak Model K ƒ.1.9 camera that had been fitted with a special lens, which had three colored bands: red, green, and blue. As the subject was being filmed, the light reflected from the subject would pass selectively through the banded color filter on the camera lens and then onto the tiny embossed lenses on the film, where the light was re-focused into separate red, green, and blue paravertical bands on the emulsion. The way that the light was re-focused into these bands of color on the lenticules was how the film was able to portray color while being projected.² Subsequently, the projector used to view the processed film would also require a tri-colored lens with a focal length that corresponded to that of the camera lens.

While this unique process was an exciting development, enabling amateur filmmakers to create color films for the first time, it required more from the amateur in terms of equipment and film knowledge than any other 16mm film stock. This speaks highly of the interest and enthusiasm for filmmaking that Marvin and Bertha Lugar possessed. Because both Marvin and Bertha make appearances in these home movies, it is clear that both of them had expertise in operating the film camera and would take turns shooting these home movies of their family.

By 1930, Kodak was actively marketing Kodacolor film stock with the Ciné-Kodak Model K ƒ.1.9, with advertisements focusing on the ease of making color films at home with the family. Ads featured small children and family vacations, highlighting Eastman’s sentiment that photography should be simple. Cameras and projectors could be retro-fitted with the required equipment to film and project in Kodacolor with a “relatively small investment,” or new equipment could be purchased from a Kodak dealer at almost the same cost as traditional black and white film.

While Kodacolor was an innovative and exciting development in the early stages of color film, its days as a popular product were ultimately numbered due to the inherent limitations in its unique color-capturing process. By the mid-1930s, Kodacolor had been phased out in favor of Kodachrome, Kodak's new color reversal film stock. Because color is introduced into Kodacolor only during the act of projection, by the refraction of light through its miniscule embedded optical lenses, the process cannot be reproduced to make duplicate color prints. This proved to be a major shortcoming in the face of Kodachrome, and the ease that it provided in creating color duplicates.

Kodacolor home movie with close-up shots of flowers, as well as other shots of

greenery and botanical scenery in an unknown location. Using the available

equipment, this film has been digitized in its black and white form. However,

it remains possible to project the film in color given the proper projector setup.

Indeed, this means that each reel of Kodacolor film is truly unique in that it cannot be duplicated in its tinted form. The only way to view the film in color is through projection of the original reel of film that was used in the camera, using a projector that is fitted with the aforementioned special, tri-color lens that precisely matches the focal length of the lens used in the original camera. Otherwise, Kodacolor film shown through a standard projector lens will appear in black and white form – which is why these films can deceptively appear to be straightforward black and white film, until you take a closer look at the film stock!

Because Kodacolor film and equipment were both so short-lived, the unique tri-color projector lens is considered a piece of highly specialized and incredibly hard-to-find equipment. Unfortunately, we do not have such a lens available to us at this time. As such, the standard equipment used by the MDPI team for the digitization of the Kodacolor films from the Lugar collection captured these films in their black and white form, as can be seen in the example clips included on this page. However, given the appropriate equipment, it would still be possible to project and view these films in color.

The Richard G. Lugar Home Movie Collection is a truly wonderful example of a well-cared-for and well-loved collection of personal family films. Some of the films show evidence of repeated projection and wear. Conservation actions have been taken to repair the structural integrity of the original objects, so that they will be well-preserved in the long-term; all of the dirt and projector oil from many past viewings has been cleaned away. What remains are only the holidays, garden parties, birthdays, growing children, and other cherished memories of the Lugar family.

* * *

Sources:

[1] Ryan, Roderick T. “Color in the motion-picture industry,” SMPTE Journal, (July 1976), 496-504.

[2] Ryan, Roderick T. A history of motion picture color techinology, (New York: Focal Press 1977), 51-55.