Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, American edition, 1871.

Charles Darwin. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. 2 vols. New York: Appleton, 1871. First American edition. With a gift inscription in both volumes, “To Dr. Frank Hamilton, with Compliments of H. M.W.” [unidentified]. New York, October 16th, 1871.

Descent of Man has been called Darwin’s “most Victorian” book (Michael Ruse), partly because of his dated view that man generally is “more powerful in body and mind than woman” (chapter 20). At the time, however, it was a bold attempt to convince a skeptical public that humans, for all their noble qualities, were a product of the same forces that have shaped the lower animals, with males trying to impress or battling for the favor of females, in the hope that they will choose them over others. A fresh reading reveals how funny Darwin’s book is, as when he charges that those who scoff at the argument that humans share the development of their canines with “ape-like progenitors” inadvertently display those very same canines in the process, thus revealing, “by sneering, the line of [their] descent” (chapter 2). Darwin explains why it is both difficult and then again easy for human observers to understand the phenomenon of female choice among birds: “If an inhabitant of another planet were to behold a number of young rustics at a fair courting a pretty girl and quarrelling about her like birds at one of their places of assemblage, he would, by the eagerness of the wooers to please her and to display their finery, infer that she had the power of choice” (chapter 14). While we may balk at speaking about “choice” when it comes to birds, humans are not so different from animals after all. Concludes Darwin, in his final chapter: “we really know little about the minds of the lower animals.”

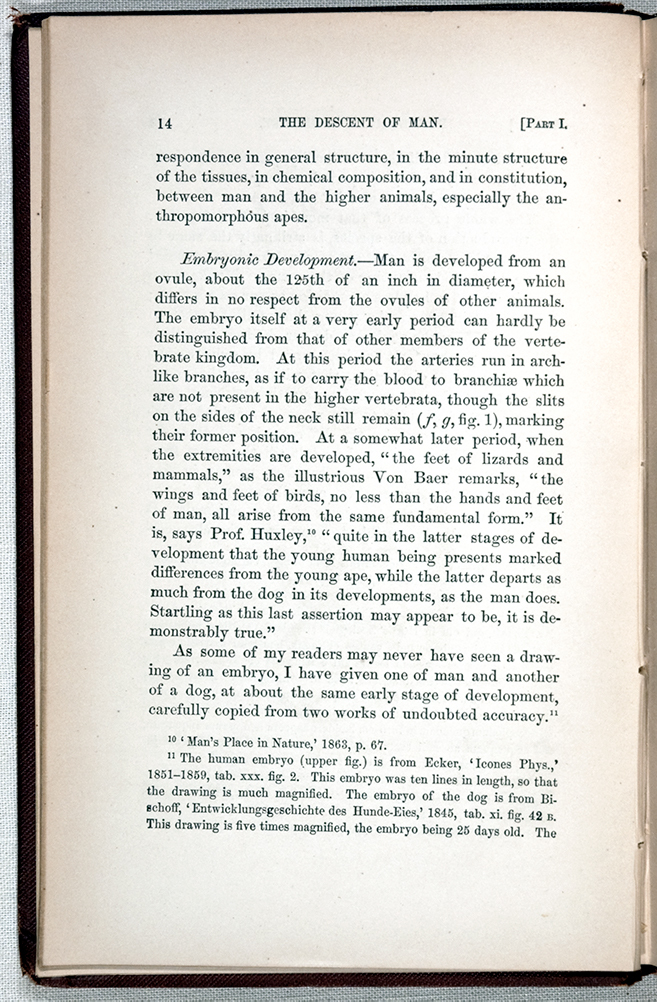

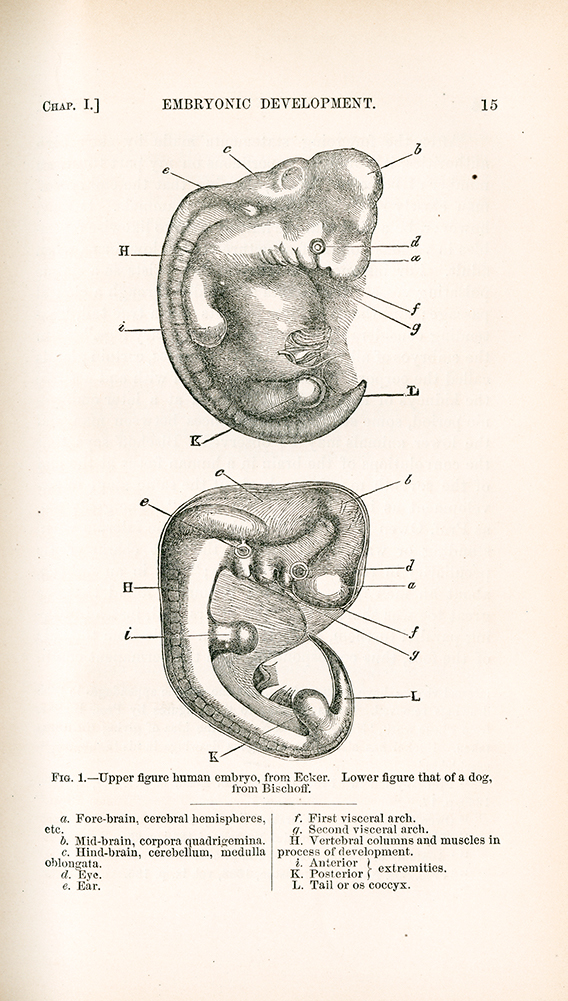

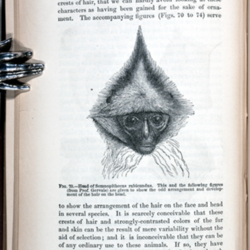

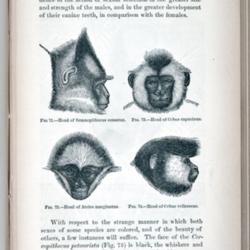

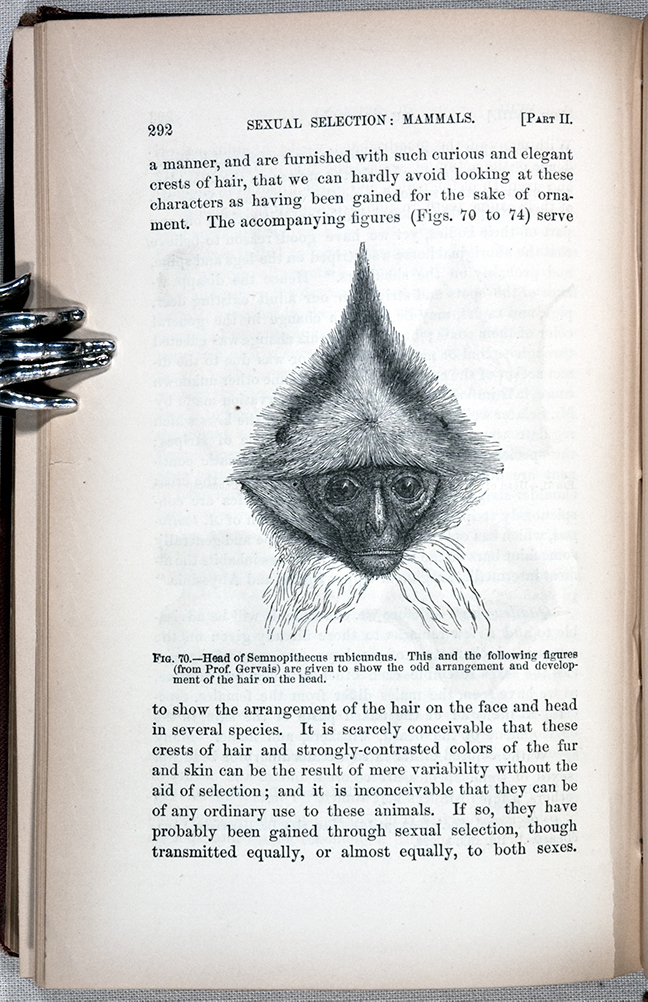

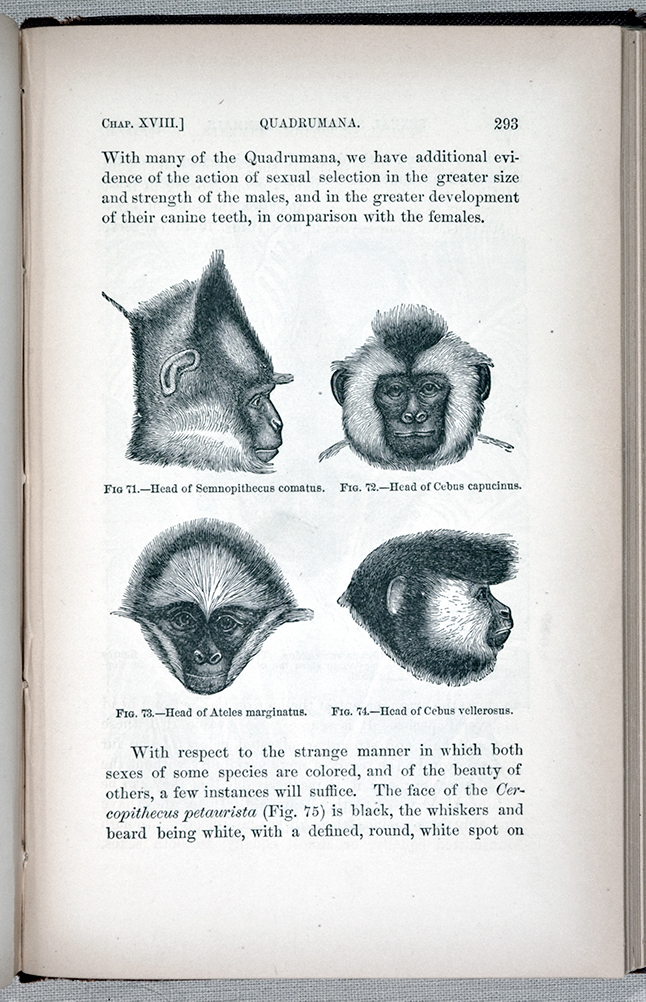

Shown here is a section from Darwin’s first chapter in which he makes the point that man “is developed from an ovule, about the 125th of an inch in diameter, which differs in no respect from the ovules of other animals,” a statement supported by drawings of a human and a dog embryo respectively. Also on display is a series of drawings of monkeys from chapter 18 (“Beauty of the Quadrumana”), sporting such fancy hair “that we can hardly avoid looking at these characters as having been gained for the sake of ornament, “ which is another way of saying that they are the result of sexual and not natural selection: “it is inconceivable that they can be of use in any ordinary way to these animals.”

Perhaps it was Dr. Hamilton himself who glued into the second volume of Descent a blurb describing the defeat of Darwin in the election of a foreign correspondent for the French Academy: “Darwin Defeated Again,” from Nature, August 1, 1872. Frank Hamilton was a New York surgeon of some eminence. He wrote the definitive orthopedic surgery text that was used by physicians during the Civil War. He was one of the founders of the University of Buffalo Medical School and a Professor at the Geneva Medical College during the 1840s. Hamilton operated on Garfield's parotid gland—see Lives of James Garfield and Chester Arthur, comp. Burton Doyle and Homer Swaney (Washington, DC: Darby, 1881), having been “invited by to do so by the President” himself (117). Apparently the purpose was to relieve the swelling. The existence of the clipping allows us to conclude that Hamilton was no great friend of Darwin’s theory. Darwin supporters, however, might derive some grim satisfaction from the fact that modern historians generally agree that Garfield could have survived if his doctors had been more capable.

The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex / by Charles Darwin, M.A., F.R.S. etc., with illustrations in two volumes vol. I[-II].

The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex / by Charles Darwin, M.A., F.R.S. etc., with illustrations in two volumes vol. I[-II].

The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex / by Charles Darwin, M.A., F.R.S. etc., with illustrations in two volumes vol. I[-II].