World’s Columbian Exposition

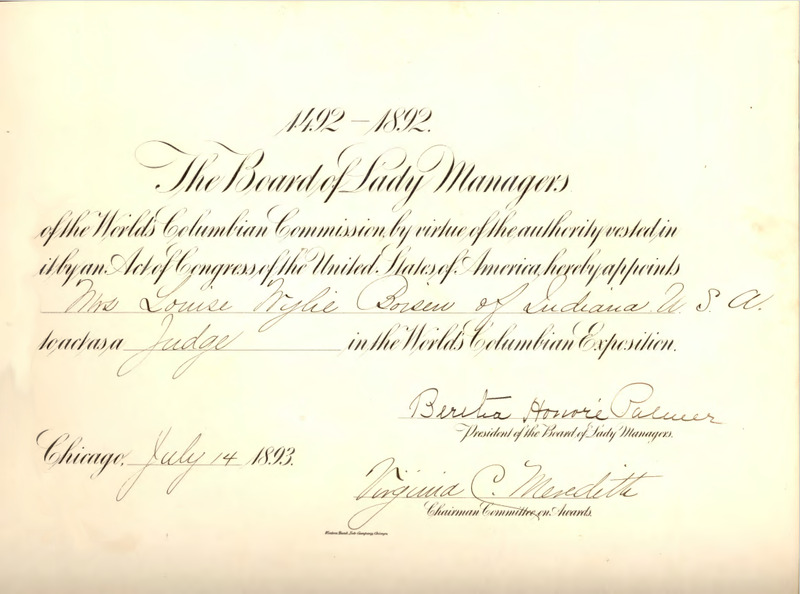

Louisa’s involvement with the Indiana Horticultural Society coincides with her foray into the national horticulture community. With the assistance of her sister, Margaret W. Mellette, who was on the Woman’s World’s Fair Commission for South Dakota, Louisa compiled an application to serve as a judge at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Margaret explained the process to Louisa:

“Now write your application, ‘I hereby apply etc for the situation’ and then take your endorsements from John Foster, Dr. Coulter, Dr. Jordan, Dr. Campbell, Arthur, Mrs, McPherson or who you can, fasten them all neatly together and get the Lady Managers (Mrs. Worleys) and the others. Then get them to send it to Mrs. Palmer or Davis.”(Margaret W. Mellette (Watertown, SD) to Mrs. Louisa M. Boisen (Bloomington, IN), January 9, 1893).

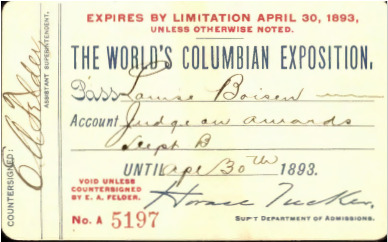

In order to apply, Louisa had to compile recommendations from the horticulture community to verify that she was qualified for the position. After a long fight, the Exposition’s Board of Lady Managers had succeeded in setting aside a certain number of judging positions for qualified female judges, and Louisa was determined to be one of those selected.1 Louisa was successful. The Chairman of the Awards Committee for the Board of Lady Managers, Viginia C. Meredith, wrote a personal letter to Louisa describing her appointment. Meredith congratulated Louisa: “You will have the honor of being the first woman to be appointed a judge in the Columbian Exposition”(Virginia C. Meredith (Chicago, IL) to Mrs. Louise Boisen (Bloomington, IN), April 1, 1893).

The appointment was only the beginning of Louisa’s Columbian Exposition journey. Along with Louisa, experts from around the world were appointed judges in floriculture. Out of fifteen judges in the category, two were women both from the United States. Louisa’s assignment was to judge the “…herbaria and other horticultural or botanical exhibits in Woman’s Building”(Bailey, Liberty Hyde. Annals of Horticulture in North America for the Year 1893: A Witness of Passing Events and a Record of Progress. United States: Rural Publishing Company, 1894., p. 57). Her first assignment was to judge the cyclamen. She wrote her parents about the process:

“I do not exactly like the responsibility of my position for it seems that under the new system there is only one judge. So I have this report on the cyclamen to make alone. But there is no competition. That is, each exhibit which is worthy is entitled to an award” (Louisa W. Boisen, (Chicago, IL) to Mr. and Mrs. TA Wylie (Bloomington, IN), February 18, 1893).

Even with the collection of recommendations which led to her appointment, judging made Louisa nervous. Working alongside other experts, Louisa’s confidence wavered. Margaret Mellette, who had urged Louisa to apply for the position offered advice. She wrote:

“But I do not believe you would be goose enough to give up a place that is as hard to get and as honorable because of a little work and worry, or what people might say or think. You were put in the place to do the best you know how. Do that and let them talk if they want… If your friends had not considered you competent I don’t think you would have got it so don’t disappoint them by making the World Fair people think you are not. Say nothing, do what you think right without consulting any of them. And don’t let them know how worried you are” (Margaret W. Mellette (Sioux Falls, SD) to Mrs. Louisa M. Boisen (Bloomington, IN), March 19, 1893).

Louisa did not have long to focus on her insecurities as the job continued. A new assignment arrived from Meredith only a couple weeks later: “Mr. Hacher asked me yesterday to ascertain if you were willing to undertake the Cineraria which is now ready to be judged or will be very soon. Mr. Hacher would be very glad to have you do this as he does not wish to appoint any other judges at this time.” Meredith continues the letter by reassuring Louisa that her place as judge is not in jeopardy writing: “He is inclined to think that the Chief of the Department has no right to object to a judge under any circumstances whatever” (Virginia C. Meredith (Chicago, IL) to Mrs. Louise Boisen (Bloomington, IN), April 1, 1893). After the Exposition, Louisa ended her stint in the national horticulture community. Even so, her plants remained noteworthy. In the year following the Exposition, 1894, one of Louisa’s plants attracted over 100 visitors to view it in bloom.

Notoriety was not the goal of horticulture for Louisa. Like many in her era, she subscribed to the belief that gardening was good for ones health and morality. Reflecting on her garden, Louisa wrote:

“In it I have found health and strength, and the pleasure I have had in watching the growth and development of the plants from the seed to the formation of the bud and the opening of the flower, have more than compensated me for the work” (Louisa Wylie Boisen, “My Garden” ca. 1908, IU Archives).

Louisa believed that this was not just a benefit she could indulge in, but was available to all of society. In a paper she presented to the Indiana Horticultural Society on August 14, 1891, Louisa details many of the abstract benefits of horticulture widely accepted during the late 19th century. She acknowledges the horticultural trend sweeping the nation and boasts its benefits. She writes:

“Of late years there seems to be an increasing love for flowers in our own country… The very inutility of flowers is their excellence and great beauty, for they lead us to thoughts of generosity and moral beauty…Dyspepsia and kindred evils flee away while working with them. Mean and sordid thoughts are banished” (Louise Boisen,“Flowers a Home Educator”, Transactions of the Indiana Horticultural Society for the Year 1891. United States: W.B. Burford, 1892).

In her paper, Louisa reveals another of the era’s new ideas: acceptance of native plants. Louisa praises native plants for their availability. By appreciating plants naturally occurring in their surroundings, even the poorest were able to enjoy the healing properties of nature. Louisa was fully invested in the horticulture trend, not only becoming an expert in the plants themselves, but advocating for the more abstract benefits of nature popular at the time.

1 The Chairman of the Awards Committee for the Board of Lady Managers was Indiana’s Lady Manager, Virginia

Claypool Meredith. Meredith was an Indiana native famous in the agriculture community of the time. For more on

her and the Board of Lady Managers (p. 177) read Queen of American Agriculture: A Biography of Virginia Claypool

Meredith by Frederick Whitford, Phyllis Mattheis, and Andrew G. Martin published by Purdue University Press in

2019.