Charles Darwin. The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms, 1881.

Charles Darwin. The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms: With Observations on their Habits. Fifth thousand (corrected). London: John Murray, 1881.

This was Darwin’s last and most successful book, as well as one of his most memorable ones. Darwin argues that much of the earth, even sizable rocks, passes through the guts of busy worms, which keep what they need and throw everything else out in the form of castings. The ruins of human buildings are preserved under layers of blackish mould produced by them. Go to any excavation site in England and you’ll find worms wiggling under the rotting concrete of a Roman villa. A field behind Darwin’s own house, covered with flint stones (the largest of which were the size of a child’s head), in the course of 30 years was transformed into smooth soil. The very ground on which we walk is alive with worms transforming matter into mould. Darwin quotes an estimate by one of his colleagues that there are 53,767 of them in an acre of garden land and half that number in an acre of pasture. In these unseemly, nearly blind and deaf creatures, slowly munching their way through vast mountains of matter, Darwin had finally found the appropriate metaphor for the inexorable workings of his own data-digesting mind-machine. Like him, they had no taste for art, especially music (or so Darwin was fond of saying about himself late in life).

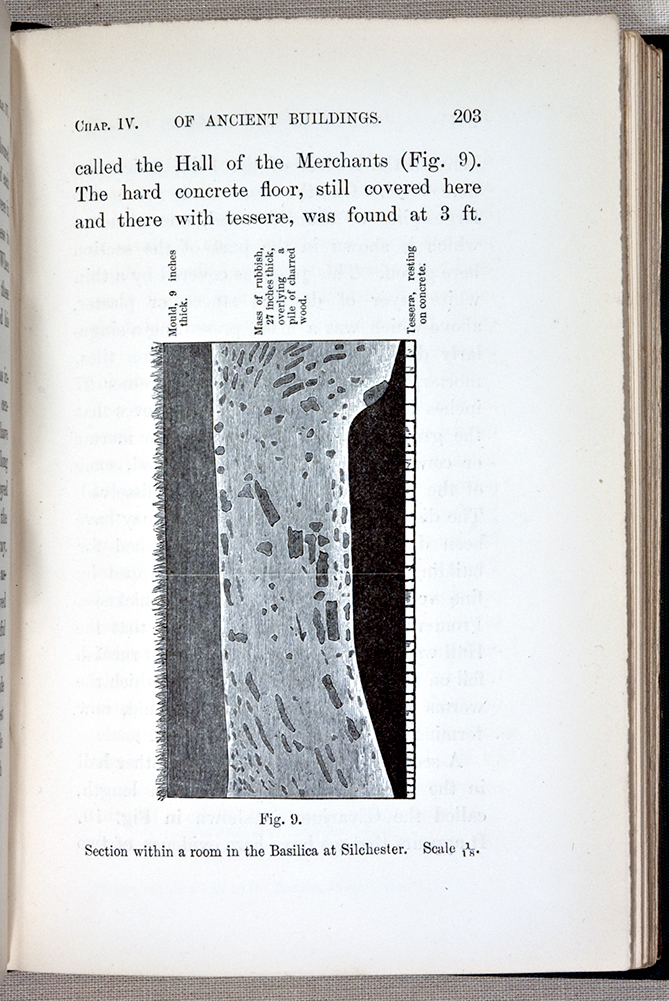

In chapter II, he famously details his attempt to find out if worms were susceptible to music. Which they weren’t: neither a whistle nor vigorous shouting nor loud piano-playing elicited a reaction from them. Apparently Darwin’s argument for the ecological importance of earthworms was so successful that one reader wrote in asking if she could still kill snails in her garden—or were they as “useful as worms”? Throughout the book, Darwin shows examples of the constant work of worms who bury buildings under them, as cross-sections of excavated Roman ruins in Silchester, Hampshire, show, which Darwin had obtained from a local informant, the Reverend Mr. Joyce.

In Fig. 9., the concrete floor of what once used to be the Hall of Merchants, has sunk 3 feet beneath the surface of the field, covered by pieces of charred wood and then a mass of broken tiles, gravel etc., all of it capped by a fine vegetable mould, the work of busy, beautiful worms.