I. Introduction: Frank L. Crone and Colonial Photography

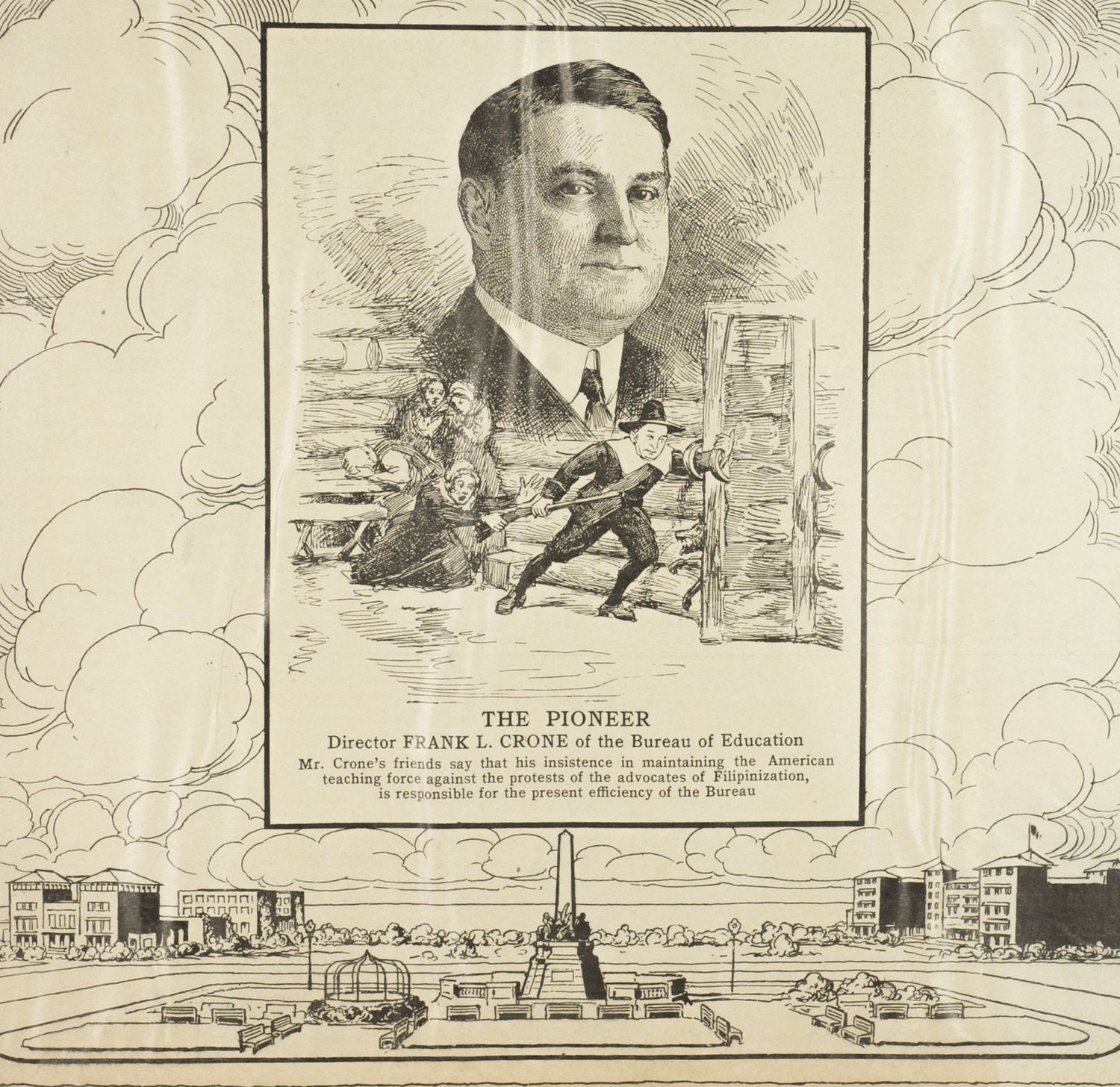

Newspaper clipping from Coleman's Weekly: The Olympic Announcer, 3. No. 31. Manila, Philippines, July 11, 1914. Crone Mss., The Lilly Library.

The caption in the clipping reads: "The Pioneer. Director FRANK L. CRONE of the Bureau of Education. Mr. Crone's friends say that his insistence in maintaining the American teaching force against the protests of the advocates of Filipinization, is responsible for the present efficiency of the Bureau."

Well before Frank L. Crone became known as "The Pioneer" (or, as some more affectionately and certainly teasingly called him, "The Fat Man Behind the Desk") at the Philippine Bureau of Education, Crone was the son of farmer John Crone of Kendallville, Noble County, Indiana. Crone left the farm to pursue a bachelor's degree in history and civics at Indiana University, graduating in 1897. After dabbling for a few years as a teacher in secondary education in the Midwest, Crone soon made an even bigger jump than farm-to-college. In 1901, he entered the foreign service, crossing the Pacific Ocean to be an English teacher at San Mateo, Philippines, not far from what is now metropolitan Manila. In the Philippines, Crone worked his way up the bureaucratic ladder: from teacher to principal to superintendent to assistant director. In August 1913 Crone was finally promoted to the Director of Education in the Philippines. Crone served in that office until June of 1916, when he left the Philippines to expand the horizons of his budding political career.

From his time in the Philippines, Crone left an impressive paper trail of meticulously kept documents, now housed at the Lilly Library. Among these, he kept a collection of eight photo albums, which offer a rare look into colonial Philippines between 1909 and 1916. Crone's photographs capture a pivotal transitional period of American colonial rule in the Islands, a time when the colonizers moved past the notion of the Philippines as a "savage" country needing to be taught proper civilization and toward the argument that the past decade of American presence as been effective in helping the Philippines "progress" toward Westernization.

The Americans, who had been present in the Philippines since their intervention in the Philippine Revolution against Spain in 1898, wanted to implement a new kind of imperialism—one that was distinct from older imperialist powers like Spain and Great Britain. By 1898, President McKinley called for this new imperialism to be one of "benevolent assimilation" with the aim of properly Christianizing (since, according to him, three and a half centuries of Spanish rule had not done so) and educating the Filipino. Education in the Philippines played a pivotal role in McKinley's plan for benevolent assimilation: the U.S. government argued that the Philippines was not ready for self-government and needed first to be taught how to be "civilized" before the Islands could ever handle self-rule. Only a long apprenticeship under a colonial regime, a God-given duty on part of the United States, could offer the Philippines proper instruction. By the 1910s, the Americans sought to showcase the colony as one that had "progressed and benefited" from about a decade of American intervention.

"Señor Emilio Aguinaldo, in front of his corn plot, Cavit, Cavite, December 16, 1912. Philippine Islands." Black and white photograph. Album #2, Crone Mss.

In Crone's photography project, the man behind the camera sought to depict not the "savagery" of the Filipino (as anthropologist Dean C. Worcester's early photography projects sought), but rather the taming and civilizing the Filipino learned from the American colonizers. In this photograph, Crone stands next to "Senior Emilio Aguinaldo" (note the caption strips him of his title as "General"), the leader of the revolution against Spain as well as the Filipino rebellion against the U.S. in the Philippine-American War, in front of the corn plot grown by Aguinaldo's son, Emilio Jr., as part of a school project. Worcester liked the photo so much that he published it in the opening pages of his two-volume anthropological study of the Philippines, The Philippines Past and Present published in 1914. Worcester's caption reads: "This chance photograph showing General Emilio Aguinaldo as he is to-day ... typifies the peace, prosperity, and enlightenment which have been brought about in the Philippine Islands under American rule." In a 1914 speech to Committee on the Philippines delivered in Washington, D.C., Worcester shared this photograph with the committee members and commented, "I may say that he is more easy to photograph now than he once was. ... Aguinaldo does not represent the highest class, although since his surrender he has been a good citizen."