IV. Conflict across the Atlantic

Letter from British MSCC to American members (undated, 1835). Letters between the two branches of the MSCC were frequently sectioned off so that different members could send messages. In the lower right corner, William Ashton's brother, Whiteley Ashton, begins his portion of the letter.

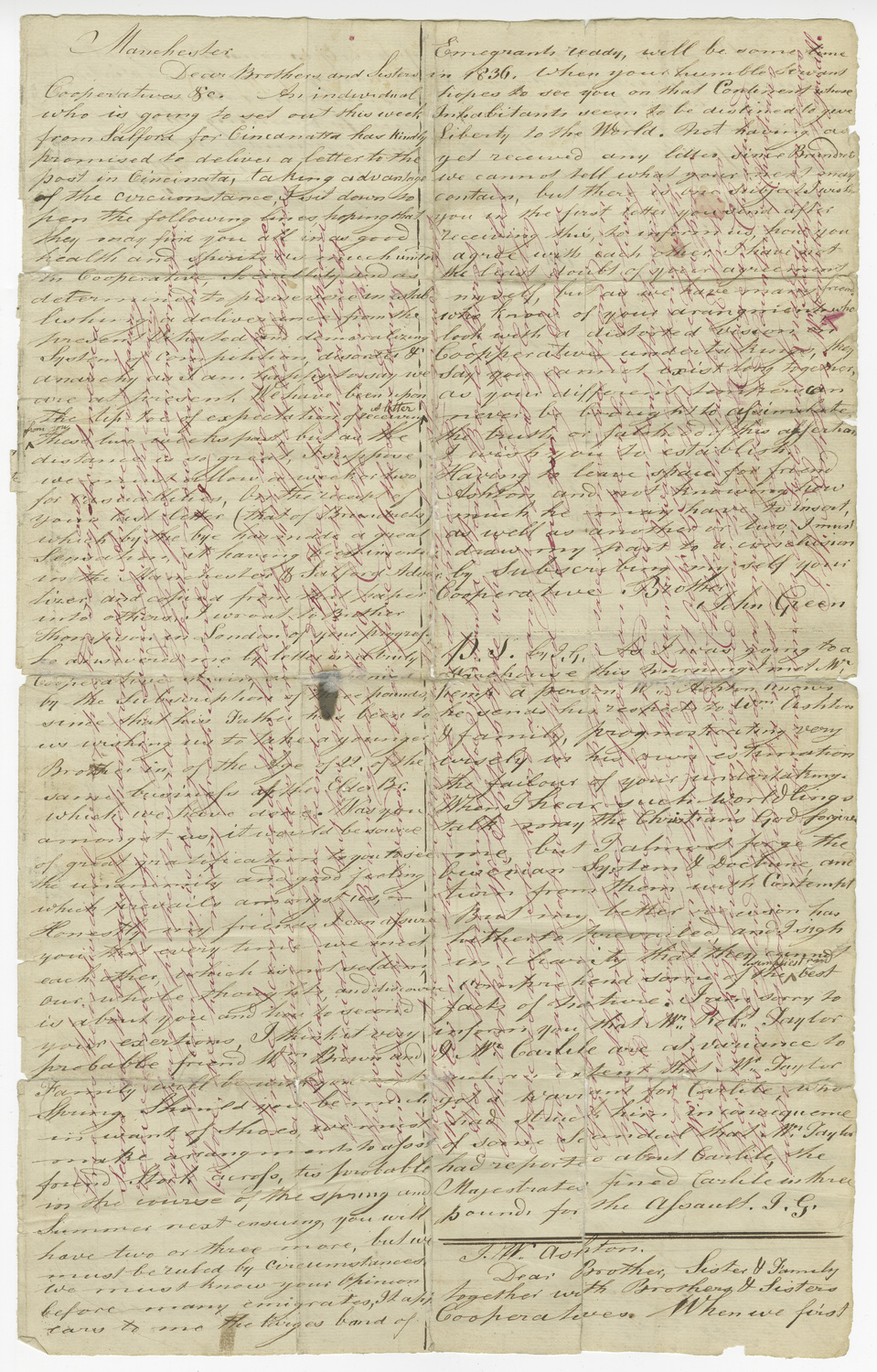

Letter from British MSCC to American members (undated, 1835), verso. Whiteley Ashton divided the paper into two long columns. The paper is in delicate condition, with a probable burn mark in the middle of the right column and multiple creases from the way in which the letter was folded to mail.

Letter from British MSCC to American members (undated, 1835), second page. Whiteley's letter continues onto the second page, which is torn where the seal was ripped open.

Letter from British MSCC to American members (undated, 1835), address page. The address on the letter - Mr. William Ashton, care of Mr. William Beesley, Beech Woods, Whitewater Township, near Scipio, Franklin County, Indiana State, North America - speaks to the remoteness of the community on America's Northwest frontier. Multiple descriptors are needed to capture its location.

"I will not cease from mental fight/Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand"

Communication between the British branch of the MSCC and the American branch was never entirely satisfactory. Members of the British branch demanded new and comprehensive details of the endeavor, while members of the American branch were too occupied with "improving" and farming the land to write as much as British members desired. Lengthy and irregular delays in the delivery of mail added to the mutual frustration. In the 1834-1835 period, nearly every letter from Britain contains a request that Ashton write more frequently and at greater length. In a letter from June 10, 1835, for instance, Whiteley tells Ashton to "continue to write regular in the same demonstrative [sic] strain, and leave not the most minute particular unrecorded." Whiteley's instructions are meant to elicit the kind of information which would reassure the British branch of the MSCC. The persistent gaps in communication made these members, especially, "low-spirited + uneasy," as Whiteley wrote to his brother on May 5, 1835. British members worried not only about the personal fate of their friends in America ("in fact we almost thought you must be dead," Whiteley writes his brother in the May 5 letter) but also about the progress of the American utopia.

The two branches of the MSCC were separated not only by the ocean and these difficulties of correspondence, but also by differences in their experience of the utopian endeavor. The (undated) letter from Whiteley Ashton on this page is representative of the tone of British correspondence in these years. Whiteley's letter begins: "When we first directed our attention towards America how warmly did our spirits glow, there was a busy movement in our souls, a kind and warmheartedness which gave relish to all our schemes of becoming possessed of land, that we could call our own, and emancipating ourselves from the competitive systems of the World." Whiteley reminds his readers of their original shared purpose in language which makes their endeavor spiritual as well as material: their efforts will free their "spirits" and "souls" from the slavery of capitalism. Whiteley also characterizes the utopian endeavor as a battle. He reflects that the emigrants have likely experienced "many trials," but urges them to continue their efforts "like... steady veterans." Perhaps in response to letters which related a deficit in enthusiasm among the emigrants, Whiteley insists that none of them should wish they were back in Manchester, where the situation between workers and their supervisors continues to be "ill." Rather, he preaches that they have "much to fight for, and much to fight against, but by and by our regiment will grow more perfect, for we are increasing in numbers. Let none desert the Standard in despair...."

Whiteley's description of the utopian endeavor as a martial struggle is ironic, given that the emigrants moved to America in part to escape the conflict which they believed was inherent to capitalism. His letter suggests that British members of the MSCC were beginning to realize, given the tepid tone and infrequency of the American correspondence, that the establishment of a utopia in distant America presented certain problems. The virulency of Whiteley's preaching testifies to the need to retain American members, who were indeed deserting "the Standard."