Browse Exhibits (15 total)

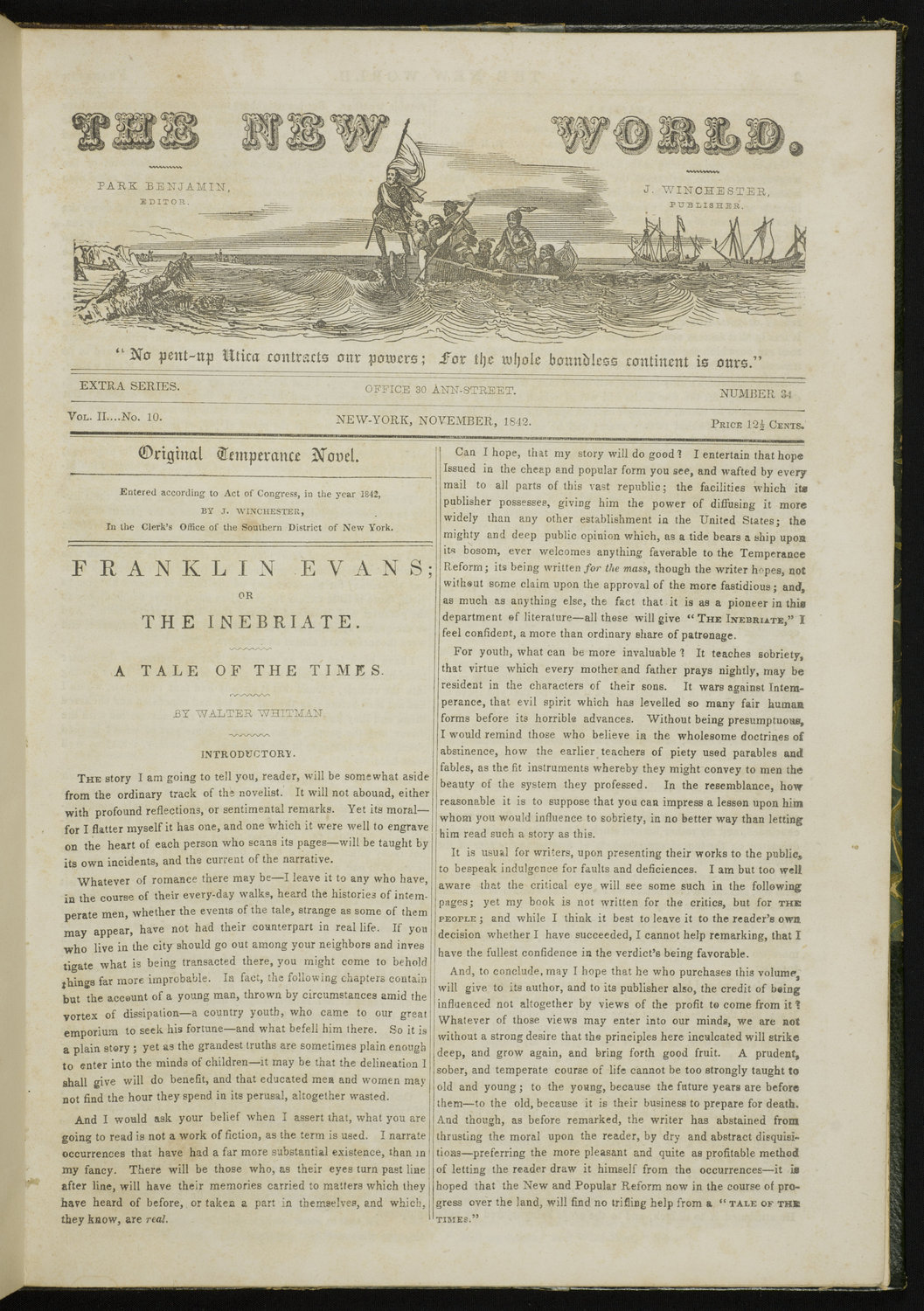

Walt Whitman at the Lilly

Compiled on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, an event that had a profound influence on Walt Whitman’s life and work, this exhibit seeks to highlight the extensive Whitman-related holdings of the Lilly Library at Indiana University Bloomington. Thanks to the pioneering collecting efforts of J. K. Lilly, the Lilly Library boasts an extraordinary collection of first editions (among them a rare copy of the final edition of Leaves of Grass in the cover Whitman rejected), manuscripts, and photographs.

When Whitman declared, in the long poem he later titled “Song of Myself,” that he was planning not “to stop till death,” he was entirely serious. His many revisions and rearrangements have caused bibliographers interminable problems, precisely because it is not always easy to distinguish between what is a new edition and what is merely an “impression.” I have followed, for the most part, the classifications used in Joel Myerson, Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993). But I also like to think of the various incarnations of Whitman’s constantly evolving poem the way Darwin (whom Whitman admired) thought of species, as varieties in permanent flux between which “no clear line of demarcation” can be drawn.

Documenting Empire: Frank L. Crone's Photographs of Colonial Philippines

As industrialization continued to spread its smoky haze all over the West and beyond by the turn of the twentieth century, the visual language of imperialism emerged in new forms. Imperialist powers displayed their colonies as spectacle in the form of photography, film, and international exhibitions in order to build, justify, and sustain their narratives of colonial rule. In the case of the United States—an emerging imperialist power at the end of the nineteenth century—some of the first films about its first colony, the Philippines, were studio-produced war scenes of American soldiers fighting against and successfully subduing unruly colonial subjects during the Philippine-American war. Sometimes films displayed real footage, such as the "technologically backward" navy of General Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Filipino revolutionary forces (first against Spain, then against the United States). Another form of spectacle, the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, went so far as to put on the first human exhibits, featuring Filipinos. Alleged to be representative of the various regions of the Philippines, Filipinos hailing from all over the Islands were shipped to Missouri (many dying on the way) to be observed by curious Americans and attendees from all over the world. Such displays intended to demonstrate how effective Americans were in “civilizing” the Filipinos, while at the same time insisting that the Filipinos were still “backward” enough such that they must remain under the tutelage of the American colonial regime. Photographs were an amalgam of the fair and films' modes of representation. Like the fair, photographs were considered to be "authentic" representations; like film, they had the ability to be easily commodified and consumed by the vast majority of the American public that needed to be acquainted with the new colony in the far-away, "exotic" Pacific.

This exhibit focuses on a collection of photographs kept by Hoosier Frank L. Crone, the American Director of Education in the Philippines from August 1913 to June 1916. About a decade into American colonial rule in the Philippines, the colonizers sought to display the "progress" of the Filipino thanks to the availability American public education. Crone's photographs demonstrate the contradictory messages of the new American imperialism based on President William McKinley's plans for "benevolent assimilation" in the new colony. Because photographs are often subject to "free-floating contemplation," in the words of Walter Benjamin, and because of their accessibility, they became useful (and frequently used) weapons in crafting imperialist narratives. In the case of Crone's photographs, they circulated in magazines and academic publications as well as among the political elite, effectively spreading the crafted imperialist visual displays of Filipino "progress" under American rule. The exhibit examines the complexities in unpacking such narratives in Crone's photographs, as well as photography's effectiveness in displaying the cultural transformation the American colonizers considered to be the centerpiece of their imperialist project.

All photographs are part of the Crone Manuscripts held by the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

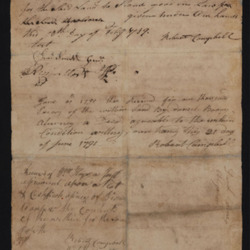

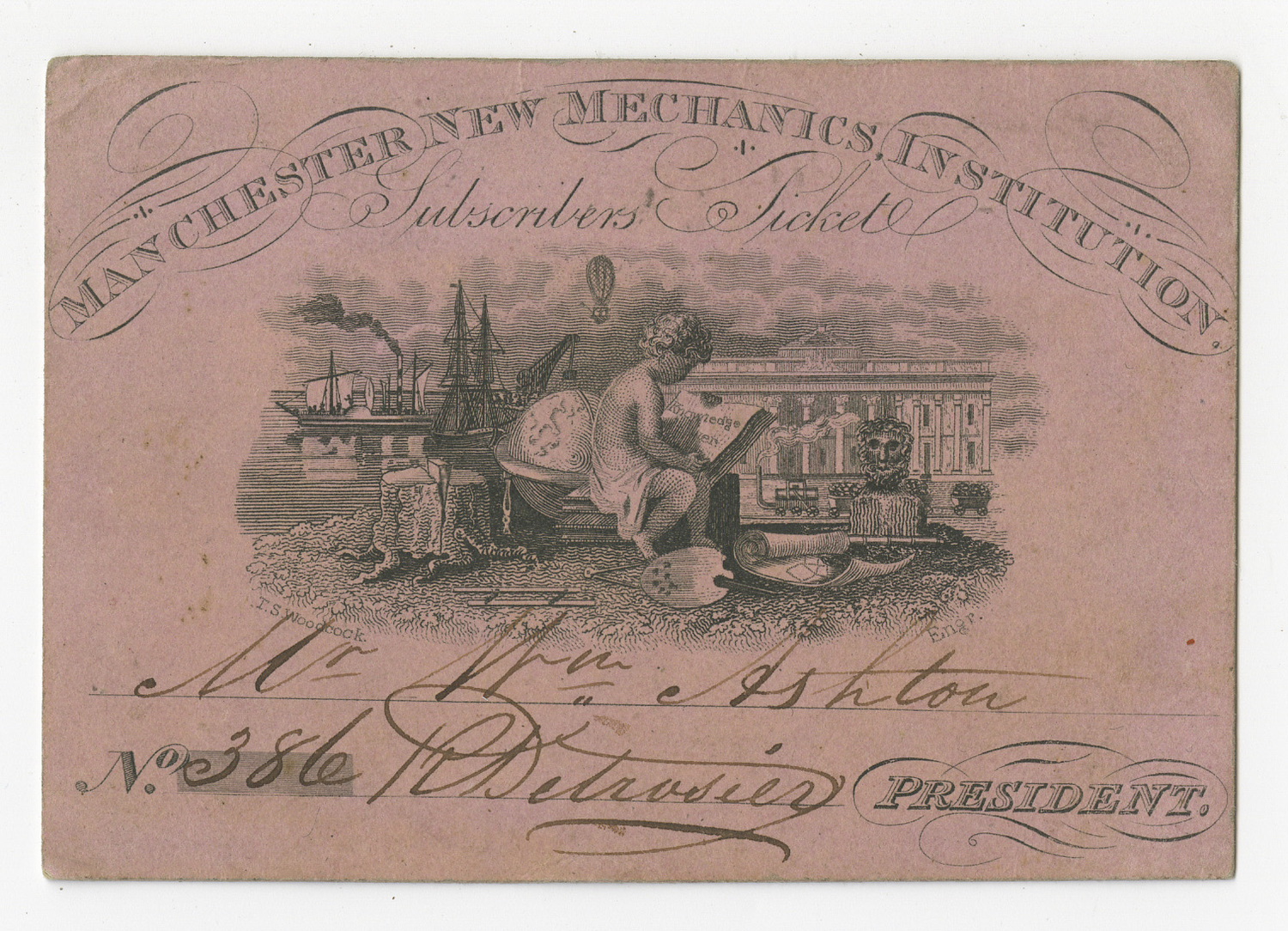

Building Jerusalem in America: William Ashton and a Trans-Atlantic Utopia

In 1834, the Manchester laborer William Ashton crossed the Atlantic with a group of fellow-thinkers to found a utopian colony in Mount Carmel, Indiana. This exhibit tells the story of that colony: from its origins in early nineteenth-century radical thought, to its establishment on the Indiana frontier, to its eventual dissolution in 1836. Ashton's endeavor was not unique. Numerous utopian societies (including, most prominently, the Shakers) emigrated from England in the nineteenth century to "build Jerusalem" on the remote edges of American civilization. While this exhibit focuses primarily on the history of Ashton's Manchester Social Community Company, it also suggests reasons for British would-be utopians' attraction to America's frontier, and addresses the challenges involved in maintaining a trans-Atlantic utopian community.

Portuguese-Speaking Diaspora

The materials in this exhibit represent five centuries of the Portuguese-speaking diaspora with emphasis on history, literature, religion and the arts.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the Portuguese-speaking diaspora stretched from Brazil and the mid-Atlantic territories of the Azores and Madeira to Africa, India, China, Southeast Asia and Japan. The 1502 Cantino map (below) shows the size of the Portuguese empire shortly after Vasco da Gama’s 1498 voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to India and Pedro Álvares Cabral’s founding of Brazil in 1500. Square-shaped red and blue Portuguese flags indicate the territories to which Portugal laid claim under the 1494 papal Treaty of Tordesilhas, which divided the non-Christian world between the Spanish and Portuguese.

Carta del Cantino. Low resolution image courtesy of Biblioteca estense universitaria

The map by Portuguese cartographer Lopo Homem-Reinéis is part of the famous 1519 Atlas Miller, held in the Bibliothèque National in France. Portuguese territories around the Indian Ocean are marked by a more detailed image of the Portuguese flag with its five shields or quinas. The bearded figure with sword and shield on the eastern coast of the African continent represents the legendary Christian ruler Prester John. The Portuguese believed that he reigned in Abyssinia and would support their proselytizing and commercial efforts.

View the Lopo Homem-Reinéis map, courtesy of the Bibliothèque National: Atlas Miller, Océan Indien Nord avec l'Arabie et l'Inde

The Cantino and Lopo Homem-Reinéis maps are reproduced in Portugaliae monumenta cartographica. vol. 1. Ed. Armando Cortesão and Avelino Teixeira da Mota. Lisbon: Comissão Executiva das Comemorações do Quinto Centenário da Morte do Infante D. Henrique, 1960. (Lilly Library call number G1001 .C5 v.1)

The majority of the items in this exhibition are from the Lilly Library Charles R. Boxer collection.

Return to the Lilly Library exhibitions list here.

Credits

This online exhibition was curated by Professor Darlene Sadlier, Department of Spanish & Portuguese, Indiana University.

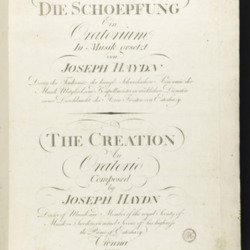

The Bible Through Music

This exhibit follows the theme of musical settings of biblical texts. By looking at various pieces of classical music based on passages from the Bible, it explores some of the ways the Bible has been interpreted and experienced over the last few hundred years. The exhibit is comprised of musical scores from Indiana University’s Lilly Library and Cook Music Library. Each item is a first, early, or otherwise noteworthy edition. Due to the potential size of such a scope, one could easily get lost in the minute details surrounding hundreds of pieces and still not come close to being comprehensive. For this reason, there are several specific limiters on the criteria for items included here.

First, all of the pieces come from a limited time period, a restriction that has more to do with musical considerations than with developments in the Bible’s history or methods of book production. This exhibit features items from the Baroque (1600-1750), Classical (1750-1820), Romantic (1820-1900), and 20th-Century (1900-2000) periods. In eras earlier than the Baroque, many common musical conventions, such as functional harmony and modern notation, were not yet standardized. The works chosen from this limited span show both how composers wrote music that was unified in these aspects, and also how they reacted to such conventions to create new styles and techniques.

Second, the exhibit is intended to represent popular names and pieces. In this regard, as well as for the consideration mentioned above, the Baroque period acts as a natural starting point. Although there were certainly masterful composers before this time, most are not commonly known in current culture. By the 18th century, however, musical giants such as Bach and Handel were entering the music scene. In an effort to heighten relevance to a wide variety of potential viewers, the exhibit focuses on the time span when well-known composers were active.

As a third consideration, this project attempts to provide a picture of the overall biblical narrative and various examples of its interpretation. It does not necessarily represent every book, but rather it highlights a variety of prominent sections in order to cover the entire scope of the Bible. This is accomplished through the exhibit's main sections—Old Testament (Pentateuch, Psalms, Prophecy) and New Testament (Gospels and Revelation).

Fourth, there are as many points of comparison between works as possible, a difficult consideration alongside the previous limitation. Nevertheless, insightful comparisons are achieved to a small degree with several of the selections. In the Old Testament portion, two pieces deal with the Exodus, namely Israel in Egypt and Moses und Aron, and two works, Symphony of Psalms and Tehillim, relate to the Psalms, both containing movements based on Psalm 150. There are also two different Passions (Bach and Penderecki) and two Requiems (Verdi and Brahms) included in the exhibit’s New Testament portion. These comparisons show a few instances of how similar sections of the Bible can be differently expressed through various types of music.

As a final limitation, the Protestant Bible is used as a basis for inclusion. This is not meant to indicate any form of preference towards the Protestant rather than the Catholic Bible, or any other canon. It is simply a matter of keeping the choices to a manageable number. Even with all of these limitations, twice as many pieces could have easily been added to the exhibit. The potential for inclusion of the Apocrypha and other versions of the canon leaves room for a more thorough look at this material in the future.

Wright-ing the Untranslatable

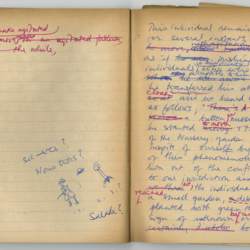

To read is to translate, regardless of the text’s language. Though the title of “translator” has carried connotations of cross-linguistic recreation – the re-writing of a text in a different language – since the 14th century, the act of reading any text results in an individualized variation of the original based on the reader’s interpretation and understanding, turning anyone who interacts with a text into a translator. Concepts of speech-rhythm, syntax, tone-values, and vocabulary play a secondary role in the translator’s cultural and literary understanding of the text, acting as instruments used to extract and reconstitute meaning.

In addition to the translated texts themselves, many kinds of sources have become available recently to translation scholars, including correspondence, manuscript drafts, translators’ notes, prefaces, and reviews, collected in part to accommodate the increased interest in translation that began in the second half of the 20th century. Though such resources do not exist for every translation, the archives of Barbara Wright, the most recognized translator of French modernist literature to this day, present a thorough collection of materials related to nearly every text she translated, providing a comprehensive source through which to study her work and the translation profession in general. The complete, thorough nature of Barbara Wright’s archive alone – seven boxes of material incorporating notes, correspondence, and all possible materials related to every one of Wright’s translation projects – makes it an excellent collection for students of translation, a case study through which to examine the practical obstacles of the profession as well as the broader impact of a translator’s work. Modernist French author Raymond Queneau’s work, which heavily explores spoken French in literature, allows Wright as a translator to push the boundaries of spoken English, turning translation into a crucial linguistic learning tool.

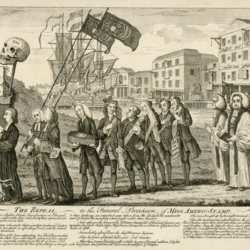

Stories of the Hoosier State: Two Centuries of Indiana Literature

Curated by Christoph Irmscher, Director, Wells Scholar Program; Provost Professor of English; George F. Getz Jr. Professor in the Wells Scholars Program

"I DON'T KNOW / WHAT IT IS ABOUT HOOSIERS," wrote Kurt Vonnegut, in a print acquired for this exhibition. "BUT WHEREEVER I GO / THERE IS ALWAYS / A HOOSIER / DOING SOMETHING / VERY IMPORTANT / THERE." In compiling this exhibition, I have striven to honor this sentiment. Rather than imposing a strict narrative line on the texts and artifacts I have included or sorting them into categories, I have tried to show that Hoosier writers, whether or not they were born and raised in this state, have always thought of their work in connection with the rest of the nation or the world at large. My goal has been to combine the familiar (Lew Wallace's Ben-Hur) with the unfamiliar (Mary Catherwood's letters to Mary Riley). The labels provide context, but the texts and artifacts, in their beauty and richness, speak for themselves. Whether it's a faux Poe poem found in Kokomo or a pin board that once graced the walls of IU professor and novelist Don Belton: stories of the Hoosier state open up new dimensions, if you are willing to listen and look.