The Kitchen: Maternal Advice Literature and Lived Experience

Three Wylie Women: A Generation of Late Nineteenth-Century Mothers

As you explore the exhibit, click on images to learn more about the artifacts and to read full transcriptions and view full-size scans of the letters.

As the most private, family-centered, and multi-purpose space of the home, this room reveals the many expectations associated with the “woman’s sphere” or the home. Cooking, cleaning, washing, caring for child illness, and more would have all taken place within the kitchen. Not only would these responsibilities be performed by mothers, but “extended mothers”, daughters, and hired domestic servants. A space utilized by many outside the role of “woman of the house”, the kitchen simultaneously embodies frenzied maternity and problematizes the ideologies of the maternal advice literature.

The late nineteenth-century technological advancements within the realm of print led to greater accessibility of publications, many specifically advertised to women. Women’s print culture, directed towards the middle-class, supported an increasingly unattainable and complex domestic ideal. The comparison of these magazines and advice manuals to the written and lived experiences of Louisa, Maggie, and Seabrook exemplifies the inconsistency between ideal and experience.

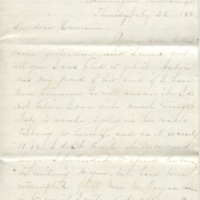

"I intended to spend the evening in writing to you, but have been interrupted . . . And now baby cries, so good night." - Louisa Wylie Boisen, July 22, 1880

For these women, juggling the varying array of expectations proved just short of impossible. Still, this ideal carried influence, leaving women to feel incapable and insufficient as mothers. In works like Godey’s Lady’s Book, the written, imagined reality lacks true experience. Pages of the magazine are dedicated to illustrated depictions of child garments, titled, “Juvenile Fashion.” These illustrations are hardly representative of the children’s clothing in the Wylie House Collection. The elaborate dresses and suits represent the fictional, idyllic childhood existing only in these publications. Meanwhile, the stained and patched, simple garments of the Wylie’s convey the truths of mothering – constant sewing, mending, cleaning messes, and caring for children, all at once.

The letters of the Wylie House collection reveal the commotions of life as a mother, allowing for an opportunity to eavesdrop on the Wylie women. But, letters only reveal a fragment of reality. For example, during Seabrook’s early years as a mother at the Wylie House, constantly surrounded by relatives, boarders, and neighbors, few letters remain that were sent between her and her close family or friends. Letters come at times of distance and during this period Seabrook interacted with her close relations in-person. Likewise, the realities, difficulties, and pressures of mothering complicated women’s abilities to attend to their letter-writing, further inhibiting our ability to peer into their worlds. Many letters opened with apologies for having not written for some time or closed abruptly due to squirmy, noisy, or misbehaving children. For example, on July 22, 1880, Louisa wrote to her husband, Herman:

“Baby is awake, lying in her cradle, talking to herself, and as it is nearly 10 o’clock I don’t think she’ll be good long. I intended to spend the evening in writing to you, but have been interrupted. First Mrs. Dr. Bryan came in to see if I intended selling my bed room set. Then Mrs. Seward was in a few minutes and after they left Aunt Lizzie stopped in on her way from church. And now baby cries, so good night.”

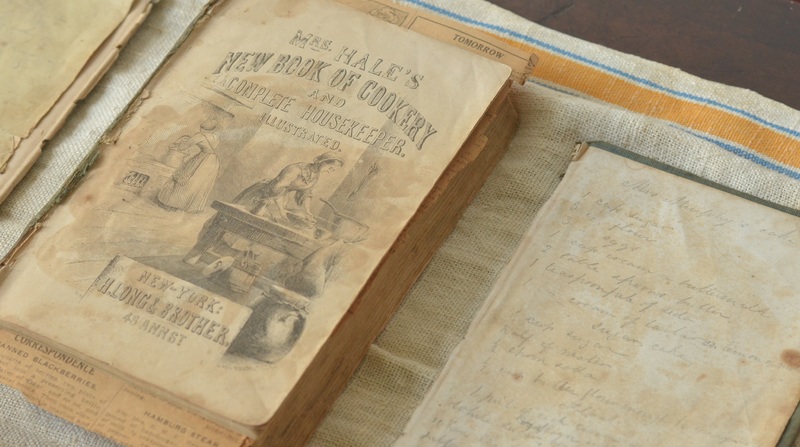

Though far from the idyllic vision of women’s magazines and advice books, the Wylie women’s lives reflect the influence of these sources. Maternal advice literature offered reassurance and “expertise” to women, who greatly desired piece of mind and assistance within their everyday. The fears and stresses of mothering simultaneously were perpetuated and relieved through these texts. Thus, the real experience of mothering existed somewhere between the letters and advise literature. Rebecca Wylie’s copy of Mrs. Hale’s New Book of Cookery and Complete Housekeeper exemplifies this blending. The recipe and remedy advice book, written by Sarah Josepha Hale, survives in shabby, worn condition with staining and scorching covering every page and both the front and back covers no longer attached. Covered in excessive scribbling, the back pages appear to have been penned by a young, unruly artist. Several handwritten receipts fill the gaps between printed recipes, including one for “Mrs. Murphy’s cake” and another for a cake recipe from another “Mrs.”. Other recipes, clipped from newspapers and magazines, some published long after the publishing date of the book, remain nestled being pages of Mrs. Hale’s recommendations. Rebecca Wylie’s book reflects a blending of the knowledge of piers and “experts”, the messy and the perfected, the goals of mothering and the real lives of mothers.

Confused on who's who? Take a look at the Family Relationship Chart at the end of this exhibit.