Personal Relationships

Maggie was especially good at developing and maintaining personal relationships—with family and friends back in the states, with Chinese families, and with fellow missionaries and other foreigners. She and Samuel tried to write to their families once a month, but, as Samuel wrote on May 25, 1850, “communication between [Ningpo] & Shanghai is somewhat irregular [so] our letters may not arrive in the U.S. regularly.”

After Maggie’s father died in 1851, she wrote, “I often wish I had some dear face to look at of the family,” and asked her mother to “get [her] dagarreotype [sic] taken and send it” (9 March 1852). Three years later, Maggie wrote that “The rain leaked through the roof and spoiled a degarreotype [sic] and several books” (20 September 1855). Despite the leaky roof, she was grateful that, as she had previously written, “The missionaries here have a comfortable support. We have as good houses as ministers generally have at home, have an abundance to eat and wear also. . . . I generally feel very contented and happy” (21 November 1851). In another letter, Maggie described the “Ningpo Maternal Association,” a weekly meeting she and the other missionary women held to discuss their roles as “wives & mothers” (November 1850).

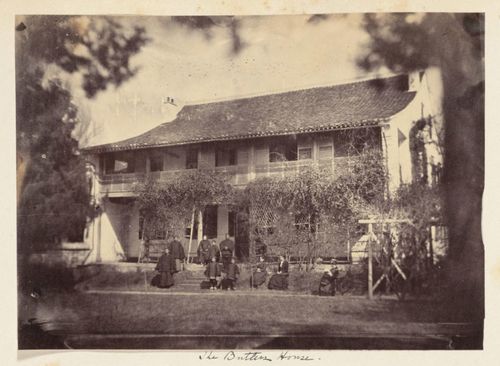

One of the Presbyterian Mission Houses c. 1880,

when occupied by missionary John Butler (1837-1885).

During the day, Maggie developed relationships with local Chinese women. The custom in Ningpo was for women to stay in their houses, away from the public eye, so Maggie and the other missionary women, who were not bound by this custom, would travel around the city to visit them in their homes. In her memoir, Helen Nevius wrote about this “work of visiting and teaching from house to house, day after day; [and] giving instruction in the truths of Christianity” (124-125).

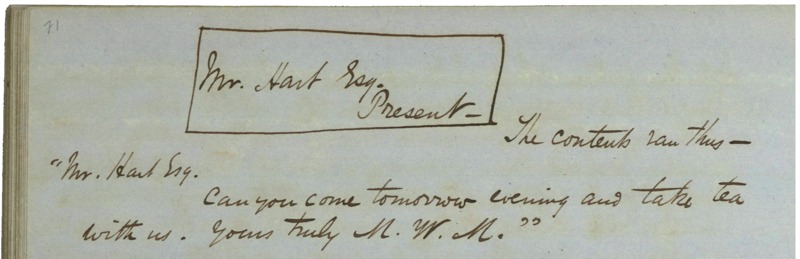

Maggie and Samuel also hosted and attended teas and dinner parties with other missionaries and foreigners in Ningpo. On October 31, 1854, Maggie invited British diplomat Robert Hart (1835-1911) to tea. Before the tea, Hart described Maggie in his diary as “long and thin—one shoulder much higher than the other—extremely narrow about the shoulders—long neck’d—and wears a very close-fitting bonnet.” After the tea, he wrote, “what a different person she is to what I had supposed her to be! She is kind—chatty, if you chat to her—amiable. . . . The evening passed very pleasantly: we had music, both vocal and instrumental, the Tea was excellent; the cakes superb; the jams delicious” (1 November 1854).