The Value of Juvenilia

I’m not grown up enough to stop laughing but I am grown up enough to wonder why I do it; and sometimes I want to kick them all into the bay and let the wind blow things clean and sometimes I want to hold on to someone’s finger. Well, this is all very confused and unpleasant….

—Elizabeth Bishop to Louise Bradley, 1928There is a wealth of information to be gained from resources that shed light on a writer's life before publication and celebrity—not only about their influences and early artistic development, but also about the attitudes and circumstances that inform their later work. Bishop's early letters fill in vital and interesting biographic information about her early life, and, more importantly, they make it possible to better read her work. We learn that Walt Whitman's poetry "makes [her] feel like singing and shouting," but we also come to better understand the deep alienation she felt at home and at school. In this way, the Bradley letters quietly humanize Bishop without compromising her reputation as a towering figure of mid-century poetic realism.

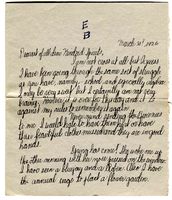

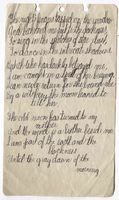

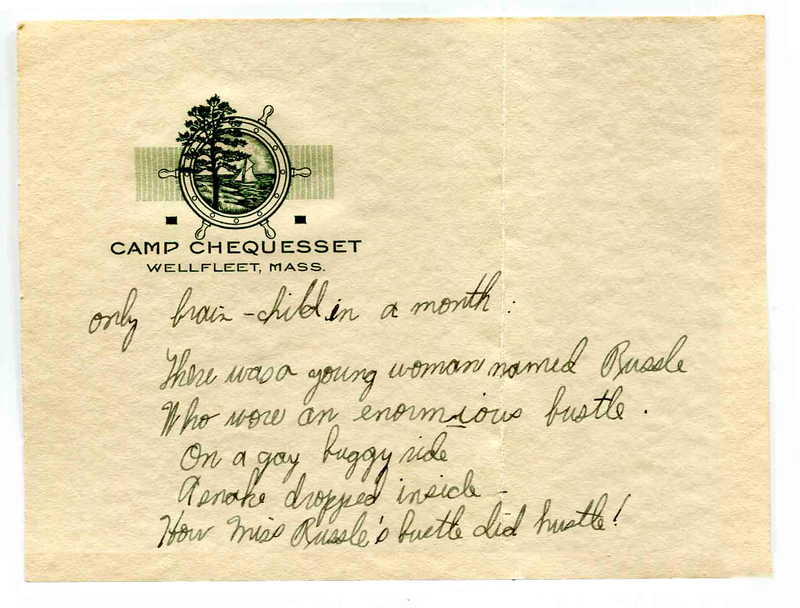

Of particular interest are several letters in which Elizabeth Bishop enclosed her early poetry. Even as an established poet, Bishop would continue to send work to Louise, and valued her opinion, but these early poems range from surprisingly competent works for a poet of Bishop's age to lightly fantastic meditations on her life as a teenager. For example, in a letter sent in March 1926, Bishop included a poem entitled "To Algebra," which she composed after receiving the "remarkable" grade of 37 percent on a recent math examination. In the letters, Bishop writes of failing her Algebra class several times, "partly on purpose," but instead of juvenile resentment, her verses on the subject betray a respect for the universality of mathematics that borders on the religious:

"The simple, set foundations of many truths,

All these are in your cabalistic signs

And yet I find you as mysterious and indefinite

As the wheeling of the worlds through space."

Bishop's letters to Bradley, which contain some of Bishop's earliest poetry, speak to her ambition and love of verse, which she would foster and refine throughout her life. Equally interesting is the modesty with which she would present these early attempts. In one letter, she meekly asks if Louise would "mind if I sent you another piece of something meant to be poetry?" She also writes: "I could never show it to anyone else and I do want to know if I am improving." These humble exchanges establish the two young women's shared interest in poetry and serve as a testament to the intimate strength of their friendship.