In 1934 Muller’s lab moved from Leningrad to Moscow and stood at the foot of an increasingly oppressive Stalinist policy. Muller felt the impact of Lysenko and the Lysenkoists immediately. He was eager to help out Vavilov but was a neophyte in Soviet politics. And the political situation was only getting more prickly. Stalin, unsettled by rumblings within the Communist Party, sought to consolidate power, increasingly through the actions of the secret police. Disturbingly enough, geneticists were often in the cross-hairs.

There was an enormous amount of general attention on scientists in the Soviet Union, as they were seen as critical to the modernization of the economy and the development of agriculture and the commensurate ability of the USSR to survive in a hostile world. Additionally, Soviet leadership was convinced of the application of Marx’s dialectical materialism to scientific work. Lenin himself had written a book on the philosophy of science and was skeptical of the applications of biology to human society. Finally, the famine of 1931-1934 had brought intense attention to all those, including geneticists, who were involved in plant breeding. In this tumultuous political context, Lysenko and his allies proved able to effectively weaponize ideology and ultimately succeeded in getting Stalin personally involved on their behalf. Altogether this meant that genetics was a very politically visible profession and geneticists were spared none of the brutal excesses of Stalin’s Great Purge.

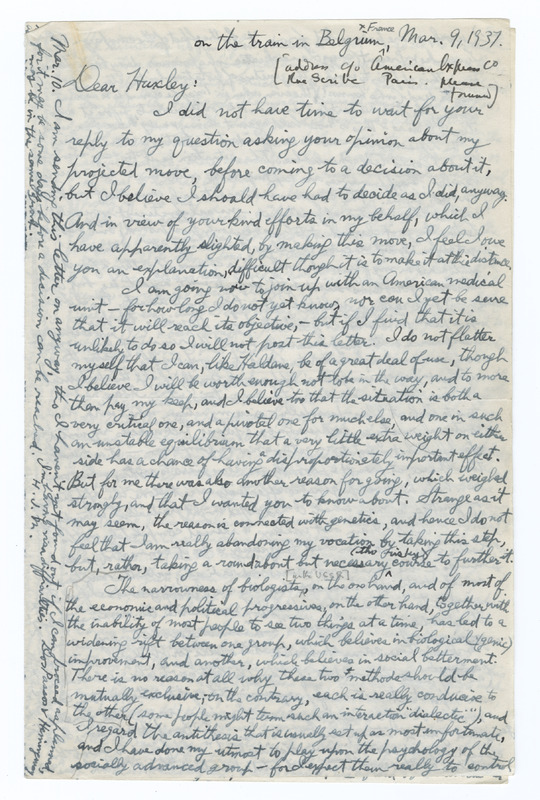

Muller could not be open in his mail from the Soviet Union. While traveling in Belgium and France, he wrote to Julian Huxley with a relatively complete account of his experiences in the Soviet Union. It is one the few detailed accounts of Muller's time there for over a decade. Muller did not feel comfortable with full disclosure until the death of Stalin in 1953.

Lysenkoism is a commonly used example of the dangers of embracing ideology over inquiry - a Soviet equivalent to climate change denial. But for Muller is was also deeply personal, and he watched as a scientific issue became a political issue, became life and death. The Lysenkoists, most notably the Marxist philosopher Isaak Prezent, played on concerns about the racist implications of genetics and the slow pace of Mendelian breeding to weld Lysenkoism and state ideology. Winning Party support, they increasingly occupied posts in the Soviet Academy of Sciences and were even placed in Muller's lab. Wary of international attention, they also succeeded in getting the planned International Congress of Genetics in Moscow cancelled.

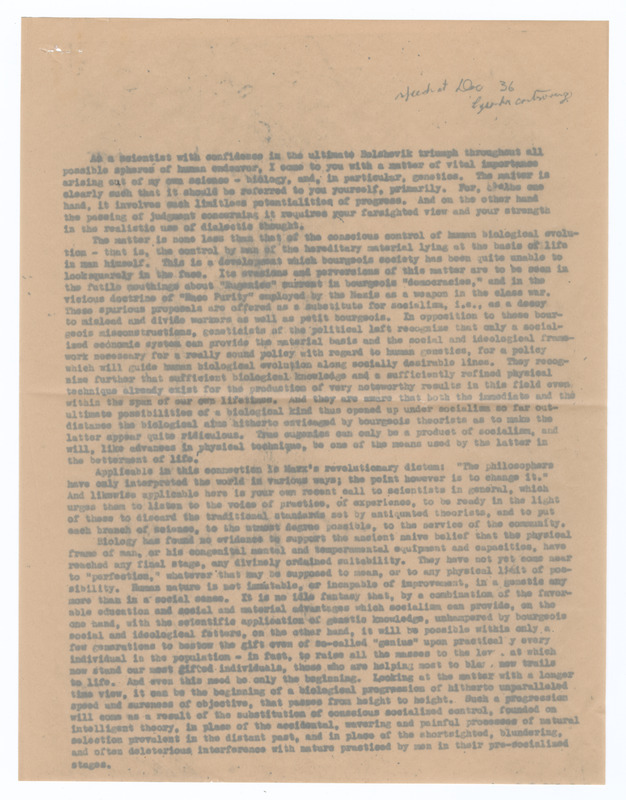

Muller's letter to Stalin is a striking piece of scientific literature. In it, he lays out his vision for a positive eugenics that would be compatible with the communist values of the Soviet Union. Positive eugenics encourages some people to reproduce more, rather than "discourage" others to reproduce less. Muller believed that by integrating socialism and eugenics, the Soviet Union could lead to both the genetic and material betterment of all its people.

Muller, never one to stand down in the face of injustice, fully inserted himself in this controversy. He felt the Soviets were painting all of genetics with a criticism that only applied to a small and reactionary stripe. His own book on eugenics, Out of the Night, which advocated for a voluntary, egalitarian, and socialist eugenics, had been accepted for publication in 1934. Muller was eager to show the Communist Party that there was a different path. Operating on the advice of his Soviet colleague Solomon Levit, Muller sent a long letter to Joseph Stalin in mid-1936 along with a copy of Out of the Night. He would not hear back about this for months, during which he waded yet deeper into the morass of the Lysenko controversy.

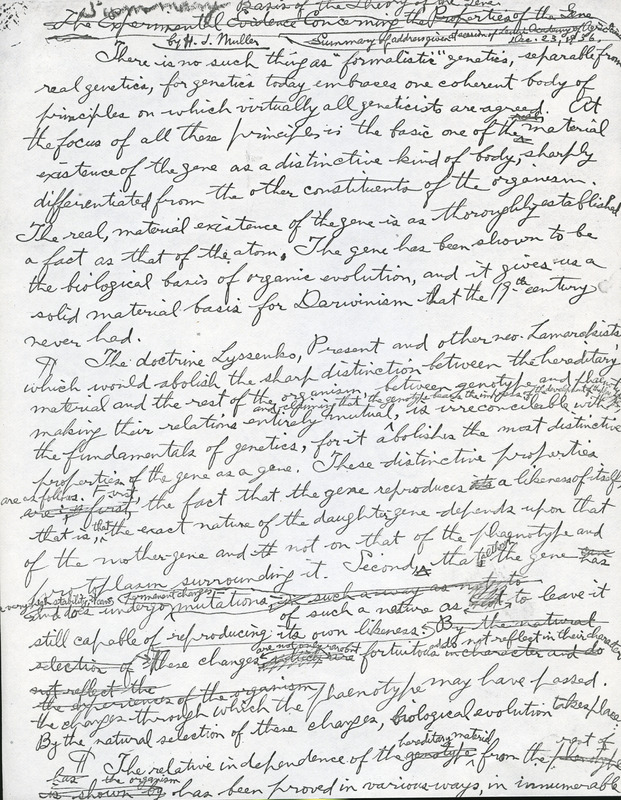

Muller's speech at the conference. It is a powerful and uncompromising statement of Mendelian genetics. Muller was never in the business of scientific compromise.

All the while, geneticists faced escalating interference from Lysenkoists and the state. Muller’s colleague Izrail Agol was arrested in mid-1936 for alleged Trotskyism, and another close colleague, Solomon Levit was denounced for spurious Nazi sympathies in late 1936.

Muller and Vavilov went on the offensive at a massive scheduled debate between traditional genetics and Lysenkoism in front of Party evaluators in December of 1936. Muller’s pro-Mendelian speech was stricken from the official record of the event, but is available in his papers at the Lilly Library. He, as Vavilov wished, explained the evidence behind Mendelian genetics and the chromosome theory. But he also accused the Lysenkoists of charlatanism and argued that it was Lamarckism which was the truly racist and bourgeois philosophy because it implied that those who came from poor and working class lineages had been genetically deteriorated by their deprivation. It was not a politic move, but at that point the debate was largely for show. The Lysenkoists occupied most of the meaningful levers of power in the Academy of Sciences and had the support of the Party. Vavilov’s hope that the facts could win out was likely already hollow.