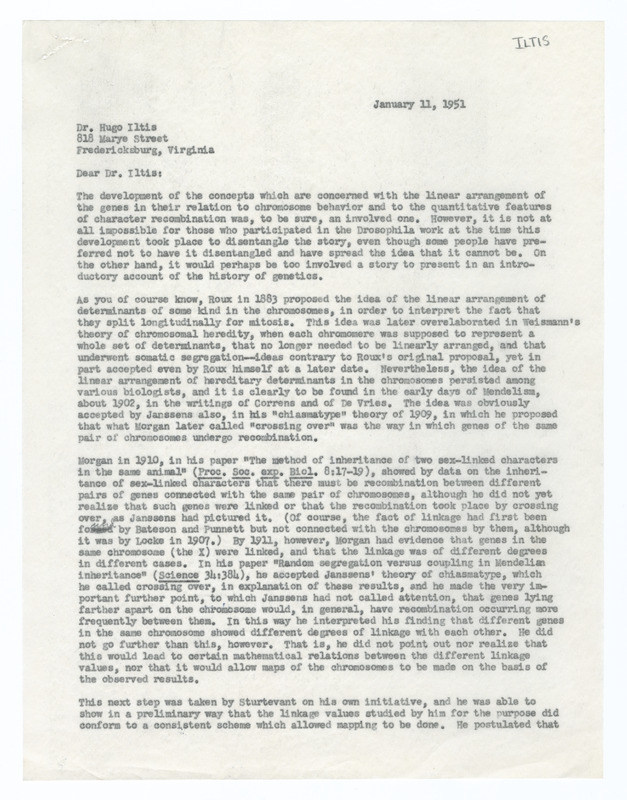

In this letter to Hugo Iltis, Muller lays out some later reflections on the early days of chromosome theory and the development of chromosome mapping.

However, researchers were discovering that even genes presumed to be on the same chromosome were not inherited together all the time. Morgan hypothesized that there was some kind of crossing over between members of the same pair chromosomes, such that genes on the same chromosome would occasionally be seperated. Morgan’s student Alfred Sturtevant, figured out how to calculate where genes were on a chromosome from the frequency of recombination. Muller himself aided in this with several key recommendations on the mathematics. This research was the basis of chromosome mapping, a critical piece of classical genetics.

Even within the fly room, Muller and his friend Edgar Altenburg were seen as radical. Many other early geneticists were quite flexible about genes, allowing that they would often blend together or otherwise be changed during the course of reproduction. Muller and Altenburg however pushed the particulate logic of Mendelian inheritance to its absolute limit. Genes were the stable core at the heart of inheritance, their expression modified by the environment and other genes, but otherwise being passed from parent to offspring with almost perfect fidelity. Notably, this describes the logic of later twentieth-century work on DNA. The similarity is not by coincidence—the groundwork was laid by Muller and Altenburg among other gene-centric classical geneticists.

The fly room may have launched Muller’s career, but unlike for Calvin Bridges and Alfred Sturtevant, who stayed with Morgan long term, it did not define it. In fact, despite Muller’s active role in the fly room, the published evidence of Muller’s contributions is astonishingly thin, with the only joint publication being the 1915 book, Mechanisms of Mendelian Heredity, together with Morgan, Bridges, and Sturtevant. Muller’s biographer. Elof Carlson, contends this likely had to do with Morgan’s lab valuing experimental demonstration over ideas and granting authorship to the experimenter. Whatever the explanation, this is a chip Muller would have on his shoulder throughout his career. It drove him to be exacting to a fault in both giving and demanding credit.