Drum-Taps

Walt Whitman. Drum-Taps. New York: no publisher, 1865. With sequel “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” Pp. 1-72 printed in New York, 1865; the sequel (pp. 1-24) in Washington, 1865-66.

This is J. K. Lilly's copy of the first edition of Drum-Taps, second issue (pace Myerson, who lists the Lilly copy as first edition, first issue).

This was, Whitman told his readers at the beginning of the volume, “a book I have made for your dear sake, O soldiers.” Never before had Whitman written under so much pressure from current events. As Drum-Taps was being typeset by Peter Eckler in New York, General Lee surrendered at Appomattox, and while Whitman was still working on an appropriate end of the poem, Lincoln (a fan of Leaves of Grass) was assassinated. The spectacular journey of Lincoln’s funeral train to Springfield, Illinois, induced Whitman to revise his plans for the volume once again and halt the binding. He rapidly composed an additional twenty-four pages, among them the famous celebration of the dead Lincoln as “the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands” (“When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”), and attached them to the finished part. About 1,000 copies of the new, hybrid edition were released. New research has shown that the numerous uncharacteristically short poems might have been written specifically to fill blank spaces at the end of longer poems—a move motivated by the high price of paper during war-time, which gives the volume an appropriately random experience: a series of fragments salvaged from the carnage.

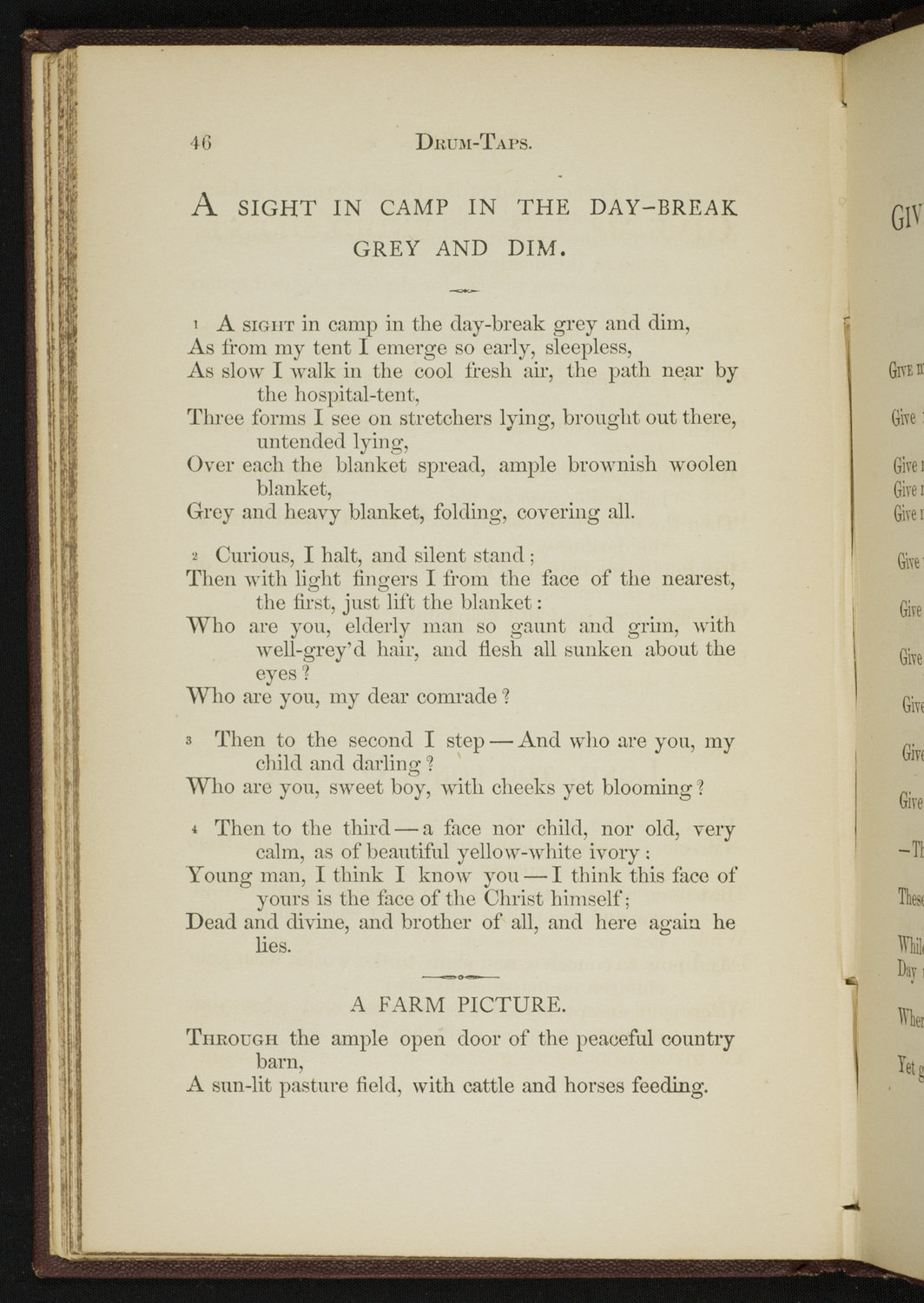

In the example shown here, “A Sight in Camp in the Day-break Grey and Dim,” Whitman’s well-known elegy for the Christ-like fallen child soldier, which uses repetition to create an intoxicating, chant-like effect, is followed at the bottom of the page by “A Farm Picture,” which seems unrelated, except perhaps as a contrasting vision. The Lilly copy is autographed “To my friend, Arnold Johnson, from Walt Whitman—with sincerest ever-loving good wishes.” Arnold Johnson was private secretary to Senator Charles Sumner and a clerk in the Treasury Department.

Whitman’s Drum-Taps won praise from fellow-writer and admirer John Burroughs and condemnation from the twenty-two year-old Henry James in The Nation. In his review, James (who himself avoided military service entirely, thanks to his famous “obscure hurt”) described Drum-Taps as “the effort of an essentially prosaic mind to lift itself, by a prolonged muscular strain, into poetry” and discounted Whitman’s hospital service: “To sing aright our battles and our glories it is not enough to have served in a hospital (however praiseworthy the task in itself) … and to be constantly preoccupied with yourself” (“Mr. Walt Whitman,” The Nation 1 [16 November 1865]: 625-6).