Chapbooks

A) Manuales

by Alex Wingate

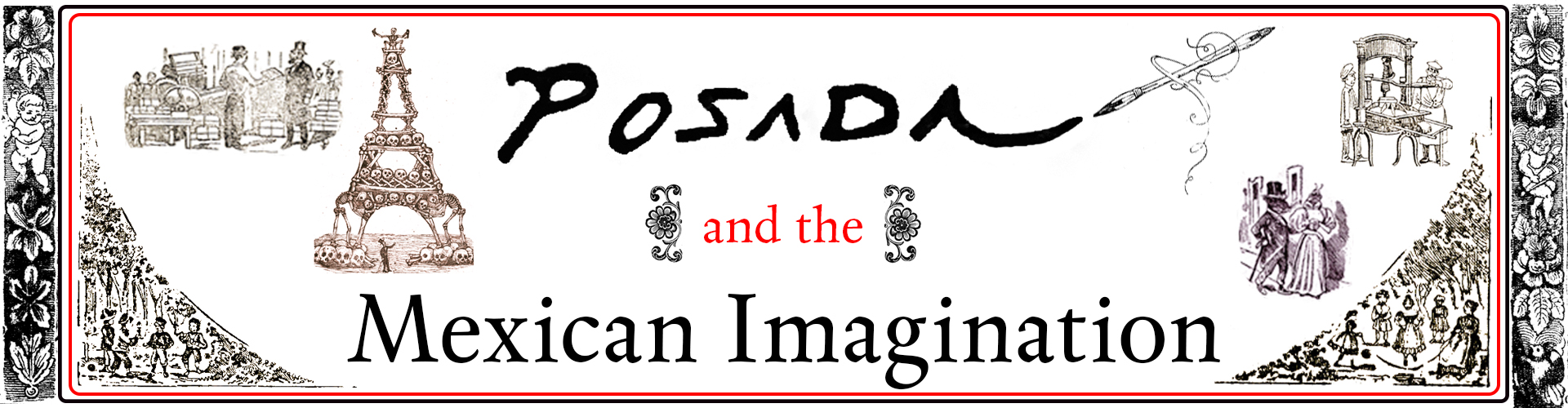

La cocina en el bolsillo, no. 3

This paper binding was designed for La cocina en el bolsillo (The Pocket Kitchen), one of a series of culinary chapbooks published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo (1850-1917). Like the other numerous chapbooks (called cuadernillos or folletos) published by Vanegas Arroyo, the audience for this work would have been quite large. These chapbooks were extremely inexpensive, ranging from 10 to 20 centavos at the beginning of the 20th century according to Elisa Speckman Guerra, and the various types of material in them (both in poetry and prose), as well as their convenient size, attracted all sorts of readers. However, this chapbook was likely specifically meant for women. There were at least two other culinary chapbooks produced by Vanegas Arroyo called El moderno pastelero and El dulcero mexicano. Both of them feature men in their cover illustrations. They are depicted working in a sweet shop and bakery, respectively, instead of a woman in a home kitchen as seen here. Their audience appears to be professional bakers, versus La cocina en el bosillo is directed towards women cooking in the domestic sphere—either for their own households or in the households of others.

The two-color illustration on the front cover identifies it as belonging to the first edition of the series which was published in the 1890s. The chapbooks in the first edition all share a very similar illustration on the front cover and were illustrated by Manuel Manilla (c. 1830-1895) and José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). It was clearly a popular series since it was republished at least twice—in 1907-1909 and then in 1913—with another possible edition in 1903. Interestingly, the series’ cover illustration changes in the 1907-1909 and 1913 versions to a woman with more modern or fashionable clothing. Though as Juli McLoone points out, the leg o’ mutton sleeves in those illustrations would have been out of fashion by 1907. Even so, this is a significant change from the woman in a more traditional outfit we see on this cover. The change in cover art might have been due to a desire to “modernize” the work, even if its contents didn’t change.

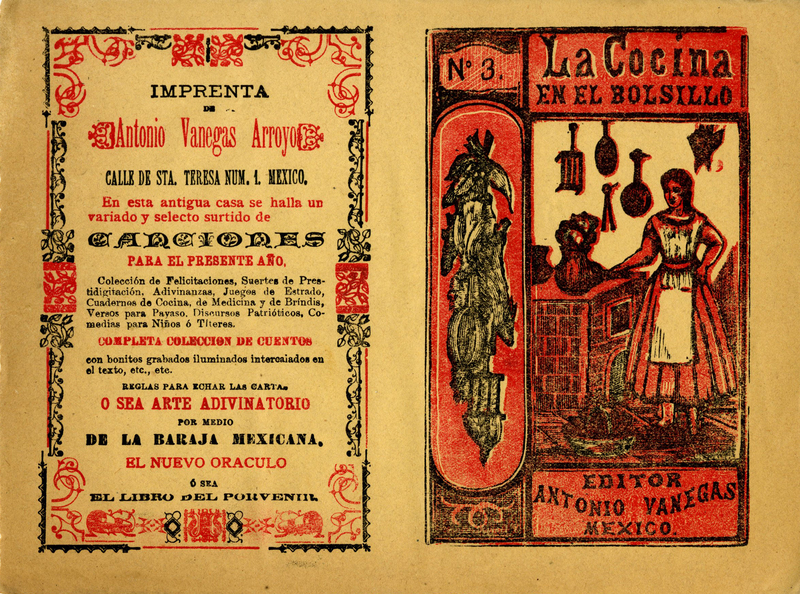

Muestras para bordado, cuaderno no. 7

Like La cocina en el bolsillo and many other chapbook series published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, Muestras para bordado (Samples for embroidery) falls into the category of manuals or practical guides. There were at least two series of manuals for handicrafts: Muestras de tejido en gancho (Samples for crochet) and this series. Compared to other chapbooks, the physical make-up of these pamphlets was special. The covers were printed on papel revolución as in the two-color cover designed by José Guadalupe Posada seen here, but inside they featured folded up patterns printed on papel de china (tissue paper). Briseida Castro Pérez, Rafael González Bolívar, and Mariana Masera point out that the audience using these embroidery patterns must have already been skilled in the art since the patterns have no instructions beyond the designs themselves. However, this lack of textual content also reveals that many of the chapbooks published by Vanegas Arroyo could have been purchased and/or experienced by individuals who could not read. Embroidery patterns certainly don’t require the ability to read words, though it could be argued that they do require a particular kind of literacy. As seen in this paper binding for no. 7 of Muestras para bordado, the illustration on the cover alone would have been enough to signal to illiterate customers the content of the work since it clearly shows a woman embroidering designs on a frame. But besides embroidery patterns and booklets on popular domestic arts, other chapbooks and ephemera produced by Vanegas Arroyo were consumed by people that could not read since they could listen to the content read aloud by others or look at the illustrations crafted by Posada and other printmakers.

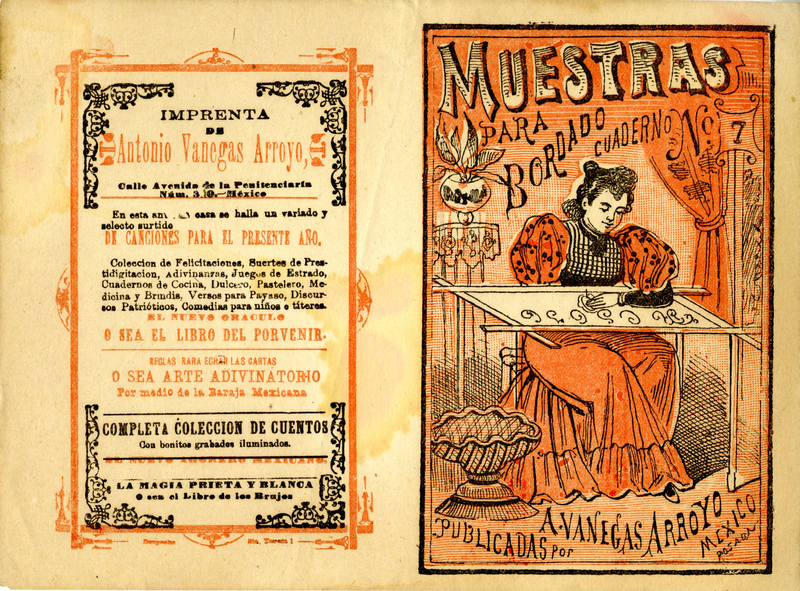

El libro del porvenir

The paper binding for El nuevo oráculo o el libro del porvenir (The New Oracle, or, The Book of the Future) has one of the most intriguing cover illustrations among the 60 bindings in IU’s Vanegas Arroyo collection. Here, a bearded astrologer surveys the heavens through his telescope and writes down his observations on the paper in front of him next to what is likely a celestial globe on his desk, surrounded by books and scrolls with one containing the booklet’s imprint (México). This work, like the chapbooks for cooking and embroidery, is a type of manual but a manual for fortune telling instead of a more “practical” activity. The instructions on the back cover show that this chapbook functioned almost like a magic 8-ball. The user would think of a question, roll three dice, and then use the sum of those dice to find a specific place in the chapbook which would then lead the individual to an image and an answer.

This publication was clearly a popular one for Vanegas Arroyo. Among the paper bindings present in this collection, 24 of them (40%) advertise that the press of Vanegas Arroyo produced and sold El nuevo oráculo o el libro del porvenir, including the bindings for the cookbook and embroidery pattern book in this exhibition. The chapbook category of fortune telling, magic, dream interpretation, and horoscopes— also known as adivinanzas — was popular with readers in general and drew upon an older tradition present in Mexico’s colonial period and in Europe according to scholars like Aurelio González, Briseida Castro Pérez, Rafael González Bolívar, and Mariana Masera. Like the astrologer in El nuevo oráculo o el libro del porvenir, these other chapbooks commonly had figures associated with magic on their covers—such as fortune tellers, wizards, alchemists, and warlocks—advertising their supernatural content. In addition to this cover, the Vanegas Arroyo collection contains covers for Secretos de la naturaleza and Relatos de ultratumba, which list recipes for spells or home remedies and tips for dream interpretation, respectively.

Works cited

Castro Pérez, Briseida, et al. “La Imprenta Vanegas Arroyo, perfil de un archivo familiar camino a la digitalización y el acceso público: cuadernillos, hojas volantes y libros.” Revista de literaturas populares, vol. XIII, no. 2, 2013, pp. 491–503.

“El moderno pastelero.” Mexicana, repositorio del patrimonio cultural de México, https://mexicana.cultura.gob.mx/en/repositorio/detalle?id=_suri:MUNAE:TransObject:5bce89637a8a02074f8338e5. Accessed 9 Apr. 2022.

González, Aurelio. “Literatura popular publicada por Vanegas Arroyo. Textos que conservó la memoria.” Literatura mexicana del otro fin de siglo, edited by Rafael Olea Franco, El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Lingüísticos y Literarios, 2001, pp. 449–68.

López Casillas, Mercurio. “Coleccionar inéditos o cronología incompleta.” José Guadalupe Posada: el gran ilustrador de lo mexicano: catálogo de exposición, edited by Cuitláhuac Quiroga Quiroga Costilla, Museo de Historia Mexicana, 2012, pp. 21–35.

López Torres, Danira. “Los impresos populares de la casa editorial de Antonio Vanegas Arroyo.” La modernidad literaria: creación, publicaciones periódicas y lectores en el Porfiriato (1876-1911), edited by Belem Clark de Lara and Ana Laura Zavala Díaz, Universidad Autónoma de México, 2020, pp. 357–75.

McLoone, Juli. “La Cocina En El Bolsillo: A Turn-of-the-Century Pocket Cookbook Series.” La Cocina Histórica, 9 June 2014, https://lacocinahistorica.wordpress.com/2014/06/09/la-cocina-en- el-bolsillo-a-turn-of-the-century-pocket-cookbook-series/.

Speckman Guerra, Elisa. “Cuadernillo, Pliegos y hojas sueltas en la imprenta de Antonio Vanegas Arroyo.” La república de las letras, asomos a la cultura escrita del México decimonónico, edited by Belem Clark de Lara and Elisa Speckman Guerra, vol. 2, Universidad Autónoma de México, 2005, pp. 391–414.

B) Galería del teatro infantil

by Ari A. Plymale

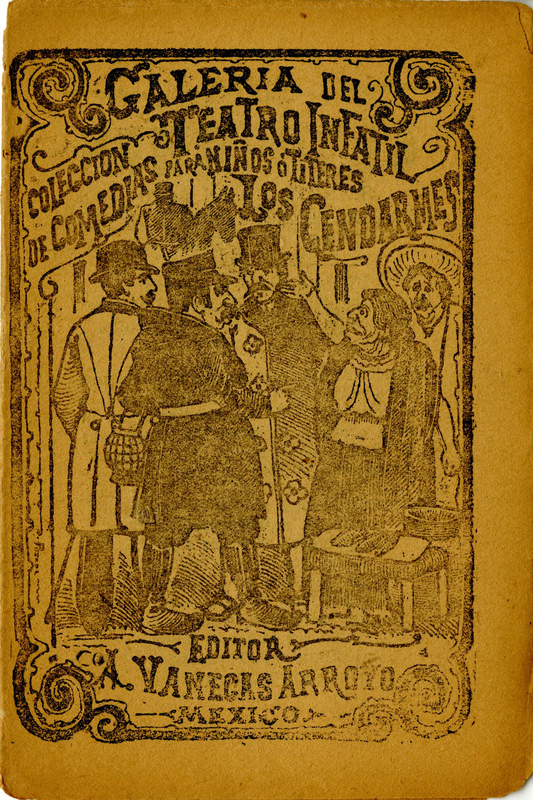

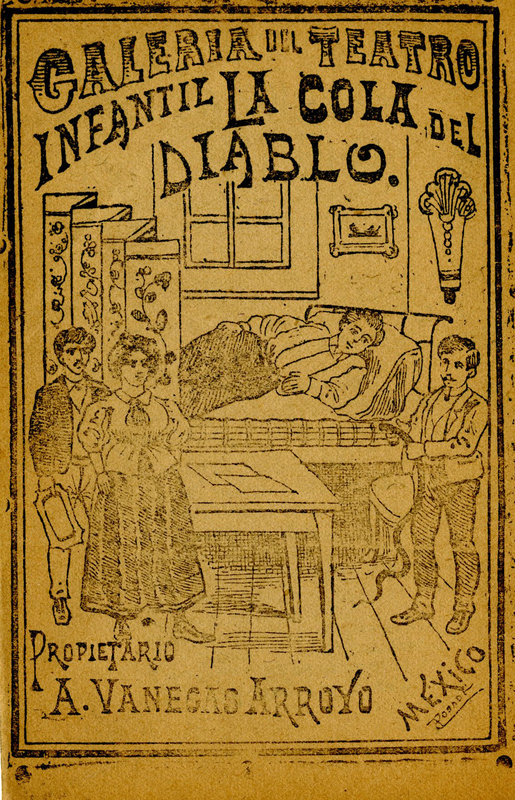

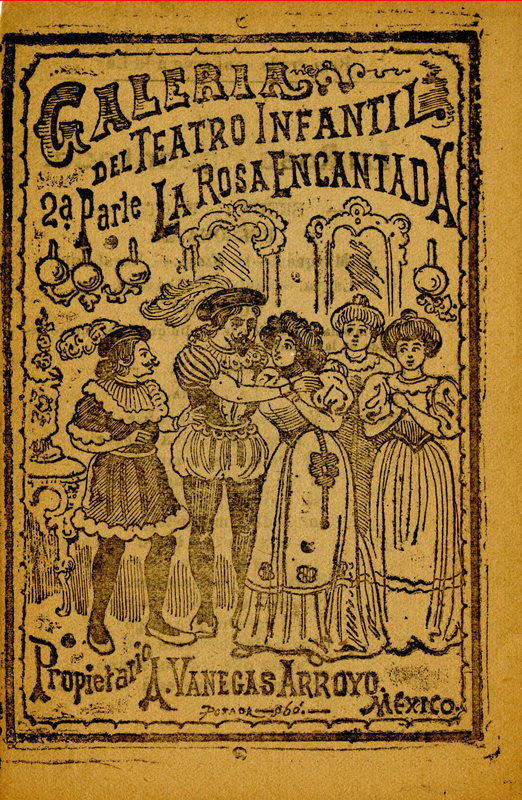

Los gendarmes (The Police Officers), La cola del diablo (The Devil’s Tail), and La rosa encantada (The Enchanted Rose) are part of a series of short plays published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo as part of the Galería del teatro infantil (Gallery of Children’s Theatre), with Los gendarmes in particular being described as part of a “colección de comedias para niños o títeres” (“collection of comedies for children or puppets”). The works in this collection, 36 sainetes (one-act comedies) in total, were primarily written by Constancio S. Suárez and A. Romero and edited by Vanegas Arroyo, but also included adaptations of popular works (such as José Zorilla’s Don Juan Tenorio). The plays were widely available and popular among children of different social classes during the periods of the Porfiriato and the Mexican Revolution and proved to be extremely influential. José Guadalupe Posada, who worked for Vanegas Arroyo between 1889 and 1912, illustrated and signed nearly all of the covers of the works in the collection.

Los gendarmes and La cola del diablo

Both Los gendarmes and La cola del diablo are short comedies that take place in then contemporary Mexico, and both the covers by Posada and the works themselves contain elements that might be considered “costumbrista” by putting emphasis on the representation of everyday customs and social conduct. Los gendarmes follows a conflict between a gentleman and an elotera (a female corn vendor) that ultimately ends up involving the police. The cover of the booklet, an etching by Posada, depicts the confrontation at the end of the play in which two gentlemen (depicted here in European-style coats and hats) and a policeman confront the elotera, represented here as an older woman wearing clothes characteristic of working-class Mexican women (in particular her rebozo, or shawl) and a drunk man depicted in a sombrero and poncho, likely indicating him to be lower-class and recently migrated from the countryside. Posada’s artistic decisions emphasize the coding within the text of these characters as belonging to specific social classes and the role of class within the conflict.

La cola del diablo, on the other hand, takes place within a middle- to upper-class Mexican household, and it tells the story of an uncle attempting to play a prank on his nephew by dressing up as an orangutan to scare him, which fails when his nephew rips the tail off the disguise. The uncle later returns without a disguise to talk with his nephew about the future, quizzing him about his studies by asking him trivia questions. For example, he asks him “how the world has been divided” (meaning which empires dominate it), to which the nephew replies “England, France, and Spain,” either referring to which European empires were most widespread in recent memory, or possibly indicating that the script was originally written prior to 1898, when Spain lost most of its remaining colonial possessions. The uncle then asks about his love life, ultimately deciding to give his nephew his fortune so that he can marry his sweetheart, who is revealed to have been spying on the conversation behind a folding screen. The cover of the booklet, an etching by Posada, depicts this final scene, representing the interior of a middle- or upper-class Mexican household, with its characters in clothes typical of the early 20th century. This etching, much like many of Posada’s other covers for the collection, can be read as a possible staging of this scene, with all of the characters posed with their bodies towards the viewer and the folding screen arranged so that the characters behind it would be visible to an audience.

La rosa encantada

La rosa encantada, is also part of this series, but unlike other works in the collection, was published in two parts, of which this is the second. The plot of La rosa encantada concerns a Marquis who during his travels encounters an empty palace with a beautiful garden guarded by a beast. Part One ends with one of the Marquis’ daughters, Rosalinda, coming to confront the beast. The second part, pictured here, depicts the confrontation between the daughter and the beast, which results in the two falling in love, defeating the curse of an enchanted rose and allowing the beast to transform back into a man, similar to the fairy tale The Beauty and the Beast. Posada’s drawing depicts the final scene of the play in which the Marquis reunites with his daughters. The cover appears to make reference to the theatre of the Spanish Golden Age, with the men (the Marquis and the now-human Beast) drawn wearing Renaissance-era clothes. However, the depiction of the daughters clearly indicates the cover to be a 19th- or 20th-century work, with the women sporting clothing and hairstyles much closer to the popular fashions of the era in which the print would have likely been originally produced.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Costumbrismo". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Aug. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/art/costumbrismo. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Carranza Vera, Claudia and Andrea Silvia Martínez. “Un ejemplo de comedia de magia en el teatro infantil de México. La almoneda del diablo (ss. XIX-XX).” Literatura mexicana, vol. 28, no. 2, 2017, pp. 9-34. https://revistas-filologicas.unam.mx/literatura-mexicana/index.php/lm/article/view/892/1036#B35.

“Costume Institute Fashion Plates.” The Met, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/libraries-and-research-centers/watson-digital-collections/costume-institute-collections/costume-institute-fashion-plates.

“La Casa Editorial Vanegas Arroyo, un negocio familiar.” Laboratorio de Culturas e Impresos Populares Iberoamericanos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1 Nov. 2021, http://lacipi.humanidades.unam.mx/ipm/w/Impresos_de_la_Casa_Vanegas_Arroyo.

Musser, Ricarda. "Digital Resources: The José Guadalupe Posada Collection at the Ibero-American Institute." The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mexica History and Culture. Edited by William H. Beezley. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 495-504.

Ortiz Bullé Goyri, Alejandro. “Algunas contribuciones del impresor Antonio Vanegas Arroyo a la cultura popular en México.” Estudios culturales: Voces, representaciones y discursos. Primera edición. México D.F.: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Azcapotzalco, 2017.

---. “Un vistazo a pequeños escaparates en la galería del teatro para niños.” en Temas y variaciones de Literatura, vol. 41, 2013, pp. 73-88.

Salcedo, Hugo. “El teatro para niños en México, una aproximación.” Tramoya, vol. 67, 2001, pp.169-172.

Tyler, Ronnie C., et al. Posada's Mexico. Washington, Library of Congress, 1979.