Why Water?

All living things need water, but for humans, water plays a particularly integral role in our society and way of life. We use it to water our crops, to transport goods, to generate electricity, to drink, to bathe, and to play. Despite its importance, water is something that is often taken for granted, especially in America. Unfortunately, many people do not have this luxury. African-American communities throughout the country face and have faced numerous struggles with water access. I will speak briefly on several ways in which water is a social issue in Black America.

Background: Redlining

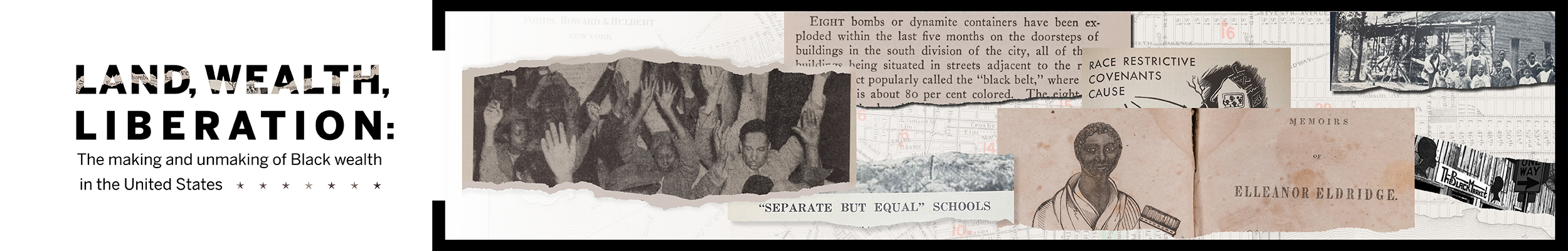

Throughout America’s history, black people have been persecuted and their opportunities have been limited. One of the most infamous ways in which this was accomplished was through a practice called redlining. Starting in the 1930s, many banks created maps that labeled neighborhoods based (supposedly) on how reliable someone from that neighborhood would be as a borrower (Brooks). Unsurprisingly, poor and minority communities were disproportionately labeled as undesirable, meaning that many black people were not permitted to take out loans. Redlining played a significant role in the development of the largely racially homogeneous neighborhoods that exist in many cities today, as white people were able to get loans to move into the suburbs while many black people were stuck in the cities. The non-legislative segregation that resulted from this practice made it easier for city and state governments to selectively invest in white areas while neglecting minority communities. Redlining and its consequences are large factors in the struggles many black communities face regarding access to water. However, while I will be focusing mostly on the effects of redlining, it is important to recognize that it worked in conjunction with other forms of racial discrimination to create the social circumstances that exist today.

Recreation

When discussing water as a social issue, many immediately think of drinking water, but discrimination regarding recreational water has also had a significant effect on how many Black Americans view and interact with water. An important example of this is the racial discrimination and violence at swimming pools in the 1930s and 40s. Prior to this point, segregation in swimming pools was actually based mostly on class, as poor people were generally considered dirty (Wiltse 124). The primary factor that changed this was the gender integration of many pools, as many white people objected to having black men swim in the same pools as white women, mainly due to the inherently “intimate and erotic” nature of swimming pools (Wiltse 124). As this integration took place, racial discrimination and violence rose, with the events that took place at Highland Park Pool in Pittsburgh exemplifying this trend. When the pool opened in 1931, there was no indication that it would be segregated, but when black people went to the pool, they were met with numerous attempts to prevent them from swimming. At first, they were turned away for not being able to show their health certificates, and then when around 50 black men returned to swim, they were beaten out of the pool (Wiltse 126). Many more small groups of black people attempted to swim in the pool over the next several years and were met with violent resistance as the police officers stood idly by. Similar events took place in St. Louis, Missouri and Elizabeth, New Jersey, while other cities made deliberate attempts to segregate swimming pools by placing them in majority-white or majority-black areas (Wiltse 139).

This history of discrimination has been a major contributor to the stereotype and reality of black people not swimming. Currently, around 64% of black kids are unable to swim, compared to 40% of white kids (Roberts). Due to the segregation that occurred and the barriers that were put in place for black swimmers, swimming did not catch on among black families nearly as much as it did for white families, so the activity did not get passed down in the same way (Roberts). Furthermore, black people are “three times more fearful of drowning” than white people, a fear that almost certainly stems from the trauma surrounding the water that is passed down the generations (Roberts). This is a tragic example of how race and racism affect our relationships with water. Discrimination that occurred long before they were born is leading black youth to believe that they don’t belong in the water.

Affordability

Another aspect of water that is becoming more and more of a concern as of late is its affordability (or rather or lack thereof). The main reason for this is aging, decaying infrastructure. Upgrading and repairing the current water infrastructure is extremely expensive, with one estimate suggesting that doing so would cost upwards of $1 trillion dollars over the next 25 years (Water/Color 24). With many cities in debt and state and federal assistance waning, the majority of this financial burden gets passed down to customers in the form of increased rates (Water/Color 24-25). Minority communities are disproportionately affected by these price increases. As a result of redlining and other historical means of destroying black wealth, the average net worth of white families ($171,000) is nearly 10 times higher than the average net worth of black families ($17,150) as of 2016 (McIntosh, et. al.). Furthermore, the only federal guideline for water affordability is “based on water costs as a percentage of median household income,” failing to take into account low-income residents (Sayed & Smith 2). This means that “Black and Latinx households … are more likely to have water affordability challenges” (Water/Color 34). On top of this, penalties for unpaid water bills tend to be predatory and damaging. Many cities place liens on debtors’ property which can result in them losing their homes. After fees and interest, these liens often grow to unreasonable amounts, with one $272 unpaid bill in Baltimore jumping all the way to $6,414 (Water/Color 42). Another common penalty is water shutoffs, which “amounts to practical eviction” because everyone needs water to cook, drink, and bathe (Water/Color 31). These are often targeted at small clusters of violators, which can result in people only a few hundred dollars in debt getting caught in the crossfire of more serious debtors and having their service disconnected (Water/Color 4). So not only are black communities facing a serious affordability crisis, they are often being harshly penalized for it instead of being given the assistance they need.

Access to Safe, Clean Water

The most prominent and infamous aspect of water as a social issue is the struggle to secure safe drinking water faced by many African-American communities. Water crises in majority black cities like Flint and Jackson are well-known by many, but similar crises are a problem in black communities nationwide. In fact, a 2019 analysis “found that water systems that consistently fail and see episodes of contamination are 40% more likely to serve people of color, and they take longer than systems in white communities to come back into compliance” (Mahoney and Wright). Jackson, whose population is 80% black, suffered from several water issues in 2021 and 2022, yet white areas of the city were “relatively unscathed” by these issues ("Our Nation's Water Systems"). This imbalance is largely due to redlining, as the segregation it caused opened the door for governments to neglect poor, black communities the way they have. As the price of maintaining and repairing water infrastructure increased, poor, minority communities were not given priority, leading to higher rates of decay and higher risk of water safety concerns.

It is important to note that the racism behind these crises is not entirely in the past. For one, the continued failure to update the infrastructure of vulnerable populations, although often justified by high costs and low funds, is undoubtedly a result of racism, or at the very least classism. The Flint crisis exemplified another prevalent form of racism, that being the continued diminishing of black voices. The first instance of this pertaining to the Flint disaster was the institution of the Emergency Manager system in Michigan. This was a system whereby a state-appointed official with the authority to overrule the mayor and other elected city officials would be assigned to cities that “suffered from financially irresponsible decision-making” (Stanley 2). After an Emergency Manager was appointed in Flint, citizens petitioned to have the law “put to ballot,” but were denied (Johnson et. al. 217). It wasn’t until a quarter of a million signatures were gathered from around the state that the law was overturned, and even then, another law was passed that put the Emergency Manager system back in place (Johnson et. al. 217). The voices of Flint citizens were not just diminished but completely disregarded. This instance is particularly significant given that it was the Emergency Manager who authorized the switching of the water source that sparked the infamous crisis. Once the source switched and Flint residents were receiving unclean, discolored water, the state government continued to ignore their concerns, assuring them that the water was safe to drink. It would take a year and a half before Governor Rick Snyder acknowledged the lead in the water and almost two years before any action was taken by the state. It’s also worth mentioning that in the midst of the crisis the Emergency Manager overturned a vote by the Flint City Council to switch back to the old water source, which could have saved hundreds or thousands from being exposed to lead (O’Donnell). The Flint crisis is a disgusting example of a city and state absolutely failing their residents and putting them in danger that could have been avoided by just listening to them.

Even the efforts for justice in Flint were not exempt from this racism. As I said before, the government ignored the concerns of community members, but this wasn’t because their efforts were lackluster or disorganized. In fact, they were extremely comprehensive and did everything they were supposed to do: “They gathered information, sought expert advice, sought meetings with government officials, kept records, protested, filed grievances, and took care of Flint’s most vulnerable” (Johnson et. al. 218). Still, it wasn’t until (mainly white) academics really began speaking up about the circumstances in Flint that anything changed, and it was these outside players whose efforts received the most recognition while Flint residents, especially African-Americans, were portrayed as victims (Johnson et. al. 218). While both groups’ pushes for justice were concerted and significant, the different reception they received shows how deep the silencing of black voices goes and how difficult it is to actually achieve environmental justice.

While the severe health consequences of water crises like these cannot be understated, it is also important to recognize the long-lasting effects of these crises on the social psyche of a community. In Flint, for instance, even 5 years after the crisis began, many still rely on bottled water and are hesitant to use tap, especially for food (“Why Flint Residents”). Cases like this in which black lives are callously put in danger by those who are supposed to be doing what is best for them lead to trauma and distrust that are difficult to break. This also damages legitimate efforts by officials to help or advise the people, as their prior experience has already shown them that these people cannot always be trusted and do not necessarily have their best interests at heart.

Conclusion

Nearly every aspect of black people’s interactions with water has been affected by racism. Because of this, black individuals’ relationships with water often vary greatly from those of other races, even if they have never directly struggled with water access. Stories and trauma get passed down through generations and can affect our view of the world dramatically.

While this project and this class focus on African-American communities, America is not the only country where water is an issue, and black people are not the only ones affected. Millions of people around the globe lack access to safe, clean water. It is for this reason that it is critical to learn about water as a social issue. By learning about these injustices, we may be able to avoid recreating them. Perhaps one day we will even be able to correct them.