Rosewood, FL

Item

Title

Rosewood, FL

Description

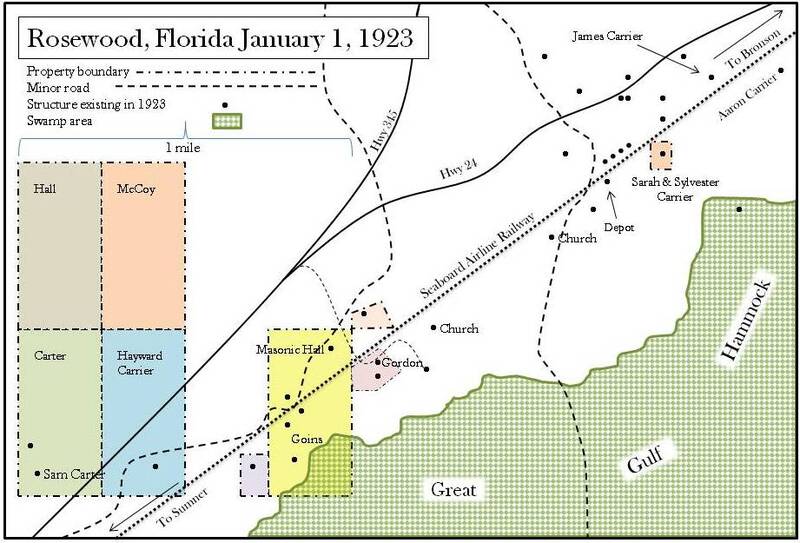

Rosewood, with a population about 120, a relatively well-off, nearly all-black town a few miles from Florida’s Gulf Coast, with an African Methodist Episcopal church, a Masonic lodge that doubled as a schoolhouse, and two general stores. Many of the citizens owned their homes, some were business owners, and others worked in nearby Sumner and at the Cummer Lumber Mill. Black-owned and -operated businesses such as M. Goins and Brothers Naval Stores Company distilled turpentine and rosin from the abundant pine trees in the area and built company housing for labor in a section of Rosewood that became known as "Goins' Quarters." At the height of their business activity, the Goins brothers owned or leased several thousand acres of land in western Levy County. Through their efforts, the town revived economically, after an earlier white business exodus.

On January 1, 1923, Fanni Taylor, a white woman from nearby Sumner accused a Black man of assaulting her. In the search for her alleged attacker, White men terrorized and killed Rosewood residents. Although the residents of Sumner believed Fannie Taylor's claim, her black housekeeper Sarah Carrier disputed the tale, and recounted to her family that Fannie Taylor's white lover, who had visited Fannie on previous occasions, was the person who assaulted Fannie on the day in question in the course of a quarrel. When Fannie's husband returned home for lunch, Carrier alleged, Fannie fabricated the story of a black assailant to protect herself.

In the days of fear and violence that ensued, many Rosewood citizens fled into the surrounding swamps, leaving everything behind, some without being fully clothed. White vigilantes burned Rosewood and looted livestock and property; two were killed while attacking a home. While all black homes and businesses were burned, two white properties remained untouched. The proprietor of one, merchant John Wright provided refuge to members of the black community. Black residents were also assisted by two white conductors on the local railroad, brothers John & William Bryce who slowly drove the train through Rosewood blowing the horn loudly and taking on women and children who had been hiding in the swamps, after which they were transported to Gainesville. The Gainesville black community took in the survivors, with families taking up to five or six refugees from the Rosewood terror. Survivor Lee Ruth Davis publicly testified “Gainesville really looked out for us.”

Historians assert that it is difficult to determine the actual number of deaths, however, the deaths of 6 Black citizens were documented: Sam Carter, who was tortured for information and shot to death on January 1; Sylvester & Sarah Carrier; Lexie Gordon; elderly and partially paralyzed James Carrier who was shot to death on January 7; and Mingo Williams. Those who survived never returned to claim their property. No arrests were ever made in the Rosewood attack.

Rosewood disappeared completely, and the black community in nearby Cedar Key went from 37.7% at the time of the riot to 0% by 1996.

Surviving residents and descendants decided to publicly tell their story in 1982. In 1993 90-year-old white resident of Sumner, Mr. E Parham testified at the Florida State Capitol about witnessing the torture and death of black businessman Sam Carter. In 1994 the Florida legislature passed an Act to compensate descendants of the Rosewood victims, prompted in part by the results of a study by a team of historians commissioned by the Florida House.

---

On January 1, 1923, Fanni Taylor, a white woman from nearby Sumner accused a Black man of assaulting her. In the search for her alleged attacker, White men terrorized and killed Rosewood residents. Although the residents of Sumner believed Fannie Taylor's claim, her black housekeeper Sarah Carrier disputed the tale, and recounted to her family that Fannie Taylor's white lover, who had visited Fannie on previous occasions, was the person who assaulted Fannie on the day in question in the course of a quarrel. When Fannie's husband returned home for lunch, Carrier alleged, Fannie fabricated the story of a black assailant to protect herself.

In the days of fear and violence that ensued, many Rosewood citizens fled into the surrounding swamps, leaving everything behind, some without being fully clothed. White vigilantes burned Rosewood and looted livestock and property; two were killed while attacking a home. While all black homes and businesses were burned, two white properties remained untouched. The proprietor of one, merchant John Wright provided refuge to members of the black community. Black residents were also assisted by two white conductors on the local railroad, brothers John & William Bryce who slowly drove the train through Rosewood blowing the horn loudly and taking on women and children who had been hiding in the swamps, after which they were transported to Gainesville. The Gainesville black community took in the survivors, with families taking up to five or six refugees from the Rosewood terror. Survivor Lee Ruth Davis publicly testified “Gainesville really looked out for us.”

Historians assert that it is difficult to determine the actual number of deaths, however, the deaths of 6 Black citizens were documented: Sam Carter, who was tortured for information and shot to death on January 1; Sylvester & Sarah Carrier; Lexie Gordon; elderly and partially paralyzed James Carrier who was shot to death on January 7; and Mingo Williams. Those who survived never returned to claim their property. No arrests were ever made in the Rosewood attack.

Rosewood disappeared completely, and the black community in nearby Cedar Key went from 37.7% at the time of the riot to 0% by 1996.

Surviving residents and descendants decided to publicly tell their story in 1982. In 1993 90-year-old white resident of Sumner, Mr. E Parham testified at the Florida State Capitol about witnessing the torture and death of black businessman Sam Carter. In 1994 the Florida legislature passed an Act to compensate descendants of the Rosewood victims, prompted in part by the results of a study by a team of historians commissioned by the Florida House.

---