Land, Wealth, Liberation Item Set

Item Set

Title

Land, Wealth, Liberation Item Set

Items

-

Black Farming and Entrepreneurship

Click Here for Inquiry-Based Lesson Plans -

Early Black Communities

Click Here for Inquiry-Based Lesson Plans -

Black Wall Streets: Centers of Business Life

Click Here for Inquiry-Based Lesson Plans -

Teaching Black Wall Streets: Centers of Business Life

Lesson plans and resource packets featuring historic Black Wall Streets. -

-

Abegunde

Photograph -

-

-

-

-

-

A Drop of Water Image 1

Photograph of a young black woman standing next to our "Drop of Water" community creative project -

Restorative Justice for Indigenous and Black Farmers

Reparations & Rematriation for Black-Indigenous Farmers is an online mapping tool that helps indigenous and black farmers connect with resources. Each pin on the map represents a farm and clicking on the pin takes the viewer to information about the farm, its current production and current resource need. The map complements the work of the National Black Food and Justice Alliance. In a 2019 review, authors Horst & Marion evaluate the literature on landownership concluding that systematic exclusion of non-whites beginning with enclosure during the settler colonial period, continuing with the Homestead Acts, the New Deal era Farm bills and discriminatory lending practices by the USDA has resulted in monopolization of agricultural land in the US by white males, with no progress being made to the present day in land ownership by minorities. Although the authors state the data limitations explicitly, the findings are striking "White, non-Hispanic males comprise the vast majority of all landowners, owner-operators, and tenants. In terms of race, 97% of landowners, 96% of farm owner-operators, and 86% of tenants are White. Meanwhile, farmers that identify as African American/Black, Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander/Hawaiian make up about 3% of non-operating landowners, 4% of owner-operators, and 14% of tenants. Farmers of color were least likely to be in the more land-secure groups of non-operating landowners or operator-owners, and more likely to be in more vulnerable position of leasing land (though their numbers as tenant farmers were well below their proportion overall in the U.S. population). Meanwhile, people of color comprised about 60% of farm laborers, a very vulnerable position in farming in the U.S., with notoriously difficult working conditions and low wages" during the period of the study 2012-2014. -

The Valerie Grim Research Collection - IUScholarWorks

This collection contains the published version of selected articles by Dr. Grim, under special permission from the publishers who hold these rights. Special thanks to the Agricultural History Society, Taylor & Francis, the University of Missouri Press, the University of Alabama Press, and the University of Florida Press. This collection comprises a selection of Dr. Grim's work on land justice. Dr. Valerie Grim is a Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University-Bloomington. She holds a M.A. and Ph.D. in history from Iowa State University and received the undergraduate degree from Tougaloo College, a Historically Black College located in Tougaloo, Mississippi. She currently holds positions as Director of Undergraduate Studies and Director of the Thomas I. Atkins Living Learning Community. She is the former chair (12 years) of the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies as well as former Director of Graduate Studies. Dr. Grim is an affiliate of the Center for Research on Race & Ethnicity in Society at Indiana University Bloomington, She has engaged in diverse committee work in and outside of the academy. These efforts have spanned more than 30 years and over 60 different committees, many of which involved engagement with students and collaborations with academic and living communities throughout the United States and Africa. As a scholar, Grim researches and publishes in the area of twentieth and twenty-first century African American rural history. She has conducted research and provided lectures in North America, Europe, South America, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. -

Pigford v Glickman

In the 1999 Pigford v Glickman decision, the US Supreme Court recounted the creation of the US Department of Agriculture in 1862 while Congress debated the provision of land for freed enslaved persons, and the reversal by President Andrew Johnson of the Freedmen’s Bureau policy to sell or lease unoccupied or confiscated land to formerly enslaved persons during Reconstruction. Despite this reversal by government, by 1910 African American farmers owned or occupied and worked 16 million acres of farmland with 925,000 African American farms in the United States by 1920. The judge noted that the growth of the US Department of Agriculture resulted in a dramatic decline of African American farmers, stating “Today, there are fewer than 18,000 African American farms in the United States, and African American farmers now own less then 3 million acres of land.” He found that discriminatory policies pursued by the USDA bore much of the responsibility for this dispossession and approved a class action settlement under which the federal government paid a total of $1.05 billion to farmers who filed a claim within the deadline who had experienced discriminatory treatment between the years of January 1, 1981 and December 31, 1996, in applications for farm loans or USDA benefits. Of over 85,000 claims approximately 18,000 were successful under the claims process. In addition, the time period and eligibility requirements for Pigford v Glickman claims represent only a small fraction of the history of dispossession by the USDA. -

Indiana University Press

Indiana University Press has published valuable work by authors writing about the African American Community in Indiana. An open access collection of selected chapters can be found at the IUScholarWorks open repository collection - The African American Community in Indiana. -

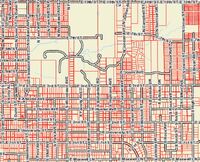

Racial Covenants in Bloomington, Indiana

The Monroe County Recorder’s Office has been working on identifying racial covenants in deeds filed with their office, in partnership with the Monroe County History Center and the Geographic Information System Division. Approximately 120 covenants have been identified to date, dating back to the 1920s. Most of the covenants relate to properties in the area immediately south of the Indiana University Bloomington campus, according to staff at the Recorder’s Office. This is painstaking work, as once a covenant is found, it is necessary to trace its existence through previous deeds to identify when the covenant was first inserted in the property deed. When the project is ready to be launched, it will be available as a geographic information layer in the Monroe County Elevate Maps system. These racial covenants are now unenforceable, but they undeniably shaped residential patterns in Bloomington. To learn more about racial covenants, we encourage you to visit the University of Minnesota Libraries “Mapping Prejudice” project, which shows how racial covenants shape patterns of race and privilege in the built environment. The Monroe County Recorder’s Office also pointed out that Indiana now provides a means for homeowners to disclaim racial covenants if they exist in your property deed. Chapter 15 of the Indiana Code, added on April 1, 2021, by House Enrolled Act 1314, permits a person to file a statement or notice that a recorded discriminatory covenant is invalid and unenforceable. This reflects the 1947 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v Kraemer. -

Student Housing at IU Bloomington

A previously unknown IU Pioneer -

![Lange, D., photographer. (1938) The Black Wax area of Texas is the outstanding cotton producing section of the western cotton belt. Near Georgetown, Texas. Williamson County Georgetown United States Texas, 1938. June. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770656/.](https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/iulibraries/files/medium/3f00555280e1fadc71bba485549b9aac2d56ab72.jpg)

Cotton Belt, United States

In the Cotton Belt, The area of the southeastern United States where cotton was grown, stretching from Maryland to eastern Texas, the Agricultural Adjustment Association (AAA) pursued plans under the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act to raise the prices of farm products by paying farmers to produce less. This was disastrous for sharecroppers as landowners simply evicted them from the land, stating that their services were no longer needed. The great majority of sharecroppers were black, but this affected white sharecroppers also. The AAA also encouraged a shift to mechanization which would require large tracts of flat land and significant capital outlay for investment in machinery. While all poor farmers were affected, poor black farmers did not have access to the sources of credit that poor white farmers did, and the credit which they did have access to was at far less favorable terms. -

Discriminatory legal land takings

In 1964, the state of Alabama sued Lemon Williams and Lawrence Hudson, removing the cousins from two 40-acre farms their family had worked in Sweet Water, Ala., for nearly a century. Despite the urging of Judge Emmett F. Hildreth to drop the suit, the state refused. The Associated Press reported that the state’s internal memos and letters on the case are peppered with references to the family’s race. Associated Press investigators located deeds and tax records documenting that the family had owned the land since an ancestor bought it on January 3, 1874. However, in 1906 the federal government designated the land as “swampland and patented the property to the state of Alabama” - a legal taking. The state was reportedly most interested in using revenue from timber sales from their land to finance state run hospitals. In a 2021 article, Jordan C Patterson argues that the Federal Government of the United States should establish a distributive justice fund to compensate African American farmers and their descendants, who lost over 12 million acres in the twentieth century. Although many black farmers were compensated for discrimination in the Pigford v. Glickman lawsuit against the USDA (about 23000 claims), this only covered farmers with claims between 1981–1996, excluding farmers who lost millions of acres during previous eras. -

USDA Discrimination against African American Farmers

Pete Daniels' 2013 book "Dispossession: discrimination against African American farmers in the age of civil rights. The University of North Carolina Press" shows that the Civil Rights period was the time during which African American farmers lost the greatest amount of land in the United States. Chapter 1 documents the engineered shift from labor intensive farming to capital intensive chemically assisted farming, coupled with outright discrimination against African-American farmers, tenant farmers and sharecroppers. It discusses how favoring the agricultural elite and agri-business interests, US Government agricultural and tax policy, together with labor saving science and technology promulgated by land grant universities and experimentaion stations, conspired to push small farmers, tenants and sharecroppers out of farming and benefit large landowners, agribusiness and non farmers who got into farming to make a loss to write off against non farming income. While both white and African-American small farmers and sharecroppers were affected, African Americans were disproportionately affected by these policies, leaving farming and losing land at a significantly higher rate than white small farmers and sharecroppers. Chapter 2 describes the Civil War Era investigation into discrimination in local USDA programs, uncovering an infrastructure of corruption pitted against poor farmers black and white: favoritism in acreage allotments, lying to and withholding information from farmers and from Negro Extension Services workers about support programs, committee elections etc., discrimination in hiring and promotion, unequal pay, training and working conditions, and discriminatory denials of federal funding. It also documents outright theft from black farmers - see the case of Cozy Ellison. Committee positions, loans, and program participation went to wealthy white elite farm families, while African-American and poor white farmers were generally ignored "but African American farmers," the investigation found, were segregated and "consistently outside the decision-making process," because of serious and pervasive discrimination throughout state and county USDA agencies which were often misreported to or tacitly supported by federal officials in Washington, which in any event had disowned responsibility for the failures at the state and county level. IU Libraries holds print and electronic copies of this book. -

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer, was someone who struggled with discrimination at the intersection of rural poverty, homelessness, blackness, womanhood, reproductive injustice and disability. She suffered from polio as a child. As a young woman, she was given a hysterectomy without her consent. In the course of her work on voter registration, she and her companions were attacked and illegally jailed by Mississippi police. Fannie Lou was beaten so badly when she was in custody that she almost completely lost her sight in one eye. Fannie Lou Hamer appreciated the emancipatory potential of landownership. In 1967 she founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in rural Mississippi. FFC owned and operated 680 acres of land at its outset. Membership was open to persons of all races, although the co-operative was formed as a response to white landowners weaponizing hunger and homelessness to retaliate against African Americans who sought to exercise voting rights. Fannie Lou Hamer's quote “As long as I have a pig and a garden, no one can tell me what to do” exemplifies the connection of land and freedom. The FFC and its members operated a pig bank, grew a wide variety of crops, operated schools, constructed homes through communal effort, provided advice to would be homeowners, and even provided disaster relief. Although the FFC only operated from 1967 to 1974 when a combination of droughts, flood, Hamer’s illness and a nationwide economic downturn caused FFC to have to sell its land to pay taxes, FFC helped and supported countless families to achieve a measure of self-sufficiency during its existence. -

Teaching about Indiana Avenue (Indianapolis, Indiana)

Introduction: -

Teaching about Hayti (Durham, North Carolina)

Introduction -

Intergenerational Wealth Mobility and Racial Inequality

Killewald and Pfeffer provide data visualizations to demonstrate how the racial wealth gap persists across generations. Animating the flow of individuals between the relative wealth position of parents and their adult children, the data shows that the disadvantage of black families is a consequence both of wealth inequality in prior generations and race differences in the transmission of wealth positions across generations: Black children both have less wealthy parents on average and are far more likely to be downwardly mobile in household wealth. By displaying intergenerational movements between parental and offspring wealth quintiles, the data underlines how intergenerational fluctuation coexists with the maintenance of a severely racialized wealth structure.