Whose lens Are We Looking Through?

As we consider the private and public histories contained in the collection, it is also important to place them within a larger historical context. The Lori Marion Collection offers a view into a particular window in time, while simultaneously standing as a valuable marker in the study of American self-documentation.

With rising home ownership and suburban living in the 1950s and the post-war increase in consumer wealth, leisure activities such as amateur filmmaking grew in popularity.5-6 The net sales of the whole photographic industry went from, “$13,238,116 in 1949 to $28,665,915 in 1952”.7 8mm film sales expanded during this time, developing into the standard for home movies and amateur filmmaking, largely due to costs.5 Moreover Kodak’s Kodachrome, used by Lori’s father, simplified color film for the amatuer market. Instead of labor-intensive manual processes to add color to film, Kodachrome film, along with color-filtered lens on the camera, instantly captured color images Development was even done at professional labs, so amateurs, like Lori’s father, did not have to properly develop film.8

Lori's father recording the family driving through US Customs back into the United States.

The Lori Marion home movies offer an entry point for observing some of the social and cultural dynamics during this period in U.S. history. For example, throughout the collection Lori’s father is the one predominantly behind the camera, potentially pointing to 1960's familial social dynamics. Indeed, home movie scholar Patricia Zimmerman writes that, “amateur-cinematography production reinforced the patriarchal character of nuclear families. The father produced twice as many movies as the mother, according to a [Bell & Howell] company report issued in 1961”.5 In the film to the left, we see Lori’s mother passing through the border from Tijuana back into California. As I watch, I think about Lori’s father behind the camera, on foot, standing between the bumper-to-bumper cars in order to capture the shot.

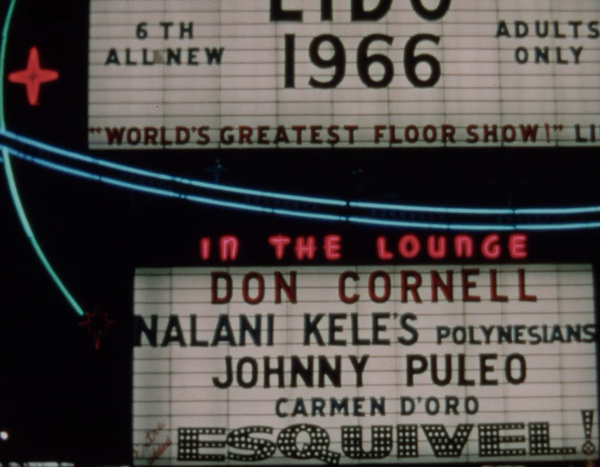

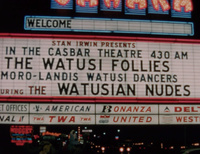

It becomes evident when watching the collection, especially evident in the family’s travel films, that no matter where the family travels, the crowds around them are predominately made up of other white families. This was due in part to the high cost of automobile ownership and the requirement of securing a multitude of days off work, conditions that racial and ethnic minorities could less frequently afford. Racial prejudice was also common for minority travelers, to such an extent special travel guides for minorities were created. One such was Victor Hugo Green’s travel guide book for black travelers called The Negro Motorist Green Book, which ran editions from 1936 to 1966.9-10 However, cultural representations of people of color leak through in the roadside attraction signs captured by Lori’s father throughout the films. For example, an electric glittering Las Vegas sign reads, “Lido 1966 Adults Only,” and below “Backroom Nalani Kele’s Polynesians,” and a huge sign in Anadarko, Oklahoma points visitors towards “Indian City USA.” As road-tripping became a prevalent way for white, suburban families to spend their leisure time, we can see in these signs two examples of Indigenous groups being exoticized and marketed as tourist destinations for these families to spectate and consume along their routes. The ability to see historic representations of race and ethnicity is valuable and important as we think about how to actively dismantle oppressive systems in the present day.