Educating the Americas

The OCIAA partnered with education institutions, like Indiana University, to disseminate government sponsored films.

German propaganda efforts grew in the western hemisphere throughout the 1930s, before the OCIAA was even formed. To counter their head start, the OCIAA embarked on a multifront education initiative in the western hemisphere. The difference in message penetration was startling, as a 1942 story on Nelson Rockefeller from Life magazine aptly explained, “When Hitler made a speech it was reported all over Latin America and translations went on the air immediately. When Roosevelt spoke, Latin America could not understand him.”55 Rockefeller understood the need for media outreach to supercede the Germans. Moreover, the OCIAA began a targeted mission to dismantle the German information network by limiting resources and business for German sympathizers. To accomplish this, Rockefeller utilized several media formats, including radio, newspaper, and motion pictures. The OCIAA also started an internal education campaign to help Americans better understand and sympathize with their neighbors.

This OCIAA film clip highlighted the German news service Transocean and its position in Colombia.

The newspapers of America’s southern neighbors were lacking American content at the formation of the OCIAA. German presence in Latin American newspapers, in which stories and translations were provided to Latin America for cheap or free, were widely available. To combat this, Rockefeller made a list of Axis-aligned newspapers and limited their supply of available newsprint while subsidizing the production costs of friendly newspapers.56 To further stimulate pro-American newspapers, the OCIAA helped to make new tax breaks for American businesses advertising in South and Central American newspapers with favorable views to the U.S., while forbidding American companies from placing ads in newspapers with questionable representations of America.57 Addressing the lack of available translations, the OCIAA encouraged translated news stories pertaining to the U.S.58 Although by late 1941 the newspaper takeover appeared to be a success,59 early efforts almost cost Nelson Rockefeller his position with the OCIAA. Wanting to start countering German newspaper propaganda, early in 1940 the OCIAA started a $600,000 ad campaign in South American Newspapers. A series of travel ads were created showing a Latin American couple’s positive remarks while traveling around the U.S., but due to export problems at the time, the economies of Latin America made leisure travel to the U.S. virtually impossible. Worse still, the OCIAA picked which magazines the ads would appear based on circulation numbers and not on the paper’s stance on Germany, leading to U.S. propaganda being shown in pro-Nazi publications. Luckily for Rockefeller, President Roosevelt rejected his offer to resign.60 Another issue with the newspaper focus was the challenge with reaching the illiterate population, which was high among the lower working classes of laborers and farmers.61 To effectively reach this audience, other forms of media needed to be examined.

In addition to education purposes these films encouraged tourism through depictions of getaways, such as this shot of a beach in Santiago, Chile.

Radio was another form of media harnessed for propaganda purposes by the OCIAA. With only six major radio networks serving the 135 million people of South and Central America in the early 1940s, the OCIAA saw an opening for expanded radio offerings.62 Especially important was creating solid competition with German radio efforts in the region, as the Nazis had been bankrolling radio programs and stations in Latin America.63 American sponsored radio content jumped under Rockefeller’s watch:

Early in 1941 the extent of United States Government short-wave radio broadcasting to South America averaged one half-hour broadcast weekly. Today the Office of Inter-American Affairs is broadcasting forty program hours daily-or 280 program hours a week-in Spanish, Portuguese, and English to radio audiences in all of the twenty other American republics.64

To spur private business interest in Central and South American radio, the U.S. changed tax laws to allow American businesses to write off broadcasting related losses.65 The hope was for greater connection and solidarity with the U.S. during the war, and the use of radio to help limit tariffs and expand trade afterwards.66 Even with these efforts, the effects of radio were likely limited. The ownership of radio sets was much lower than in the U.S., with an estimated radio ownership rate of under two percent for Latin Americans.67 Thus, unlike in the U.S., exposure to broadcasts only happened for many in group listening settings (e.g., restaurants, other’s homes).

Three children and a dog examine a poster for The Great Dictator on the streets of Colombia to emphasize the audience Hollywood has in the region.

Lastly, the OCIAA invested into film production and screening to spread the Good Neighbor message. Feature films and Hollywood were popular throughout the western hemisphere at the time. An estimated 13 to 18 million Latin Americans in 1939 flocked weekly to cinemas to see Hollywood offerings,68 and in the same year the President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Walter Wanger, explained that films were, ‘120,000 American Ambassadors’.69 Attempts to incorporate film to further inter-American solidarity included the sponsoring of artist and actor tours of Latin America, contributing to production costs for specific titles, the translation of American films for western hemisphere release, and the funding of entire divisions in some film studios. Perhaps the best example of these efforts were exhibited with the OCIAA’s dealings with Disney. Walt Disney and the OCIAA reached an agreement to: create two feature films (Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros) with final creative approval from the OCIAA and a tour of the region by their artists and animators. In exchange, the OCIAA provided financial resources such as guarantees against losses for the releases.70 In addition to feature films, the OCIAA had a heavy hand in the creation of newsreels (short films about current events frequently played in cinemas before feature films), educational films, and other short films dealing with the subject of South and Central America.71 These efforts were fruitful, with over 700 educational OCIAA-backed films being shown to audiences throughout the western hemisphere.72 Projection equipment was provided to U.S. embassies and consulates to encourage the playing of OCIAA content,73 and to reach areas without steady electricity, the OCIAA loaded film projectors onto trucks equipped with gas powered generators to visit populations which had rarely, if ever, seen moving images.74 All together, the OCIAA claimed to have five million monthly viewers to their educational productions in Latin America during the war, and a total viewership of over 200 million.75

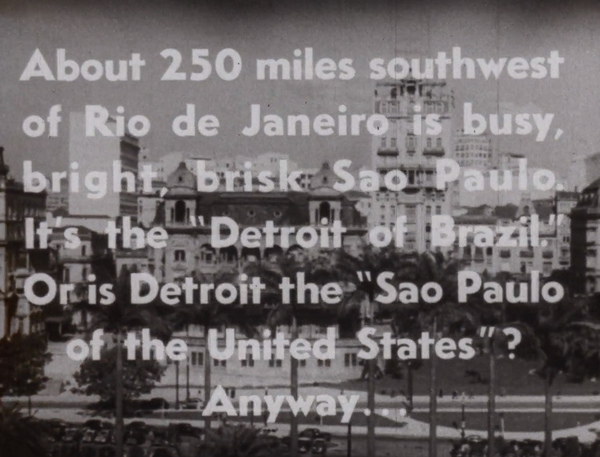

Direct comparisons between U.S. places and South and Central American places were utilized frequently in OCIAA films to establish mental images for American audiences, like this intertitle comparing Detroit and Sao Paulo.

A fundamental part of the OCIAA education plan focused on domestic audiences that, to this point in time, knew virtually nothing about the countries to the south. Initiatives in paper, radio, and film were crafted for U.S. citizens within the borders of America to build a sense of connection and inter-Americanism.76 By educating the American public on the similarities of their southern neighbors, it furthered the interventionist cause for entering into World War II and world affairs. Educational programs were established at 16 OCIAA backed centers across America, furthered with increasing partnerships from private industry.77 Here, cultural activities flowed, such as lectures from Latin American guest speakers, educational film screenings, language and history education, the issuance of publications, and even the displaying of sponsored exhibits.78 Moreover, higher education institutions partnered with the OCIAA to offer seminars and continuing education activities to regional teachers in an attempt to expand the discussion of the Good Neighbor Policy into elementary and secondary education,79 as Harold E. Davis from the Division of Science and Education at the OCIAA explained, “If education is to play a continuing role in the development of hemisphere solidarity, the rank and file of our teachers must be better informed on the geography, people, history, and language and culture of our southern neighbors.”80 To tackle the demand for skilled professionals in engineering and the sciences, the OCIAA also encouraged exchange students, and the translation of technical papers into and out of spanish and portuguese.81