Hard Times and Good Neighbors

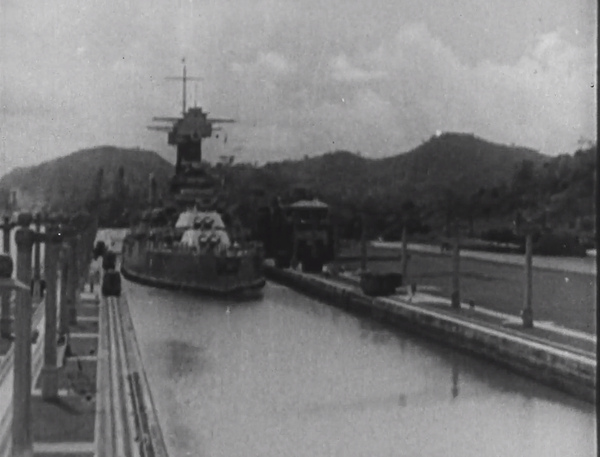

U.S. foreign policy towards the western hemisphere changed significantly through the early half of the 20th century. At the beginning of the century, American foreign policy under President Theodore Roosevelt consisted of “Big Stick” diplomacy. This policy centered on direct diplomacy and military response follow through when prompted. “Big Stick” politics relied on a large military presence, specifically a strong navy, throughout the world to accomplish objectives. When coupled with the Monroe Doctrine, a 19th century U.S. policy forbidding the colonization and interference of the western hemisphere by outside nations (mainly aimed against the highly developed colonizer countries of Europe), it led to direct military engagements in several places in the Americas, including Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.1 The frequent use of military action in the affairs of western hemisphere nations even led to the “Roosevelt Corollary” addition to the Monroe Doctrine specifically claiming the ability to interfere with sovereign nations when their stability was questioned.2 The use of military assets in Central and South American diplomacy would not last long.

The next president, William Howard Taft, fundamentally shifted American involvement in the hemisphere by favoring Dollar Diplomacy. Instead of direct military action and occupation, Dollar Diplomacy leveraged potential economic opportunity for the support of American policy objectives. It functioned by the State Department directing private U.S. investment money from banks and individuals.3 Through selectively choosing partnerships in these countries, the U.S. encouraged local governments friendly to American views. Additionally, the investments into countries, like Haiti, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua, did not open free market capitalism to grow economies, but instead created, “... a form of dependent capitalism in which their economic destinies were controlled by foreigners.”4 Dollar diplomacy continued until the onset of the Great Depression, when the world economy collapsed.5

President Franklin Roosevelt (center left) shaking hands with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

At the end of President Hoover’s term another foreign policy shift started and was embraced by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) in the 1930s. Contrary to previous interventionist diplomatic efforts, FDR’s “Good Neighbor” policy aimed to restore the trust of leaders throughout the western hemisphere leery of U.S. interests after previous approaches.6 Officials advanced the notion of Inter-Americanism to build respect with America’s southern neighbors, as President Roosevelt stated in his inaugural address from 1933, “In the field of world policy I would dedicate this Nation to the policy of the good neighbor--the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others--the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a world of neighbors.”7 Inter-Americanism focused on common geographic realities as well as shared democratic ideals.8 Private religious and philanthropic organizations expanded operations to South and Central America for philanthropic work.9 Such organizations could still be persuaded by the U.S. government to pursue objectives of interest to the government though. For example, the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army was successful in pursuing the charitable Rockefeller Foundation’s health initiative to change its emphasis to focus on yellow fever, as it was a goal for the Surgeon General.10 As with previous strategies, stability and economic influence were main objectives, although this policy emphasized greater bilateral agreement on trade, policy, and military assistance. To achieve these ends, the U.S. often supported dictatorships and repressive regimes while trying to connect the similarities of these nations with America.11

This clip from the 1943 OCIAA film Brazilian Quartz Goes to War highlighted the unique quartz deposits of Brazil to U.S. radio communications in World War II.

The Good Neighbor policy became increasingly important as the European powers rearmed and escalated hostilities leading up to World War II. In large part, South American resources allowed Germany to rebuild their economy and military in the 1930s.12 Early in the war the British blockaded German ports, halting the export of resources from the western hemisphere. This accounted for a third of exports from these countries, threatening economic stagnation.13 Furthermore, according to American defense official calculations German gains in North Africa put the Nazis within flight range of Brazil. The fear was of possible invasion or occupation of South America by Germany, especially concerning strategic war resources of rubber, iron, and quartz.14 American intelligence also revealed pockets of German sympathy by the people of Latin America, spurred on by a concentrated propaganda campaign in the 1930s by the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.15 If allowed to continue, potential invasions of the region by Axis powers could harbor local sympathies and create more issues for the U.S. To address these challenges, the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) was established with Nelson Rockefeller leading the efforts.

American business Caterpillar, makers of heavy machinery, was critical for infrastructure creation in the region.

Local textiles became increasingly desirable to Americans, as this image of an American fashion buyer inspecting some Ecuadorian textiles shows.