The Guest Room: Financial Issues and Widowhood

Three Wylie Women: A Generation of Late Nineteenth-Century Mothers

As you explore the exhibit, click on images to learn more about the artifacts and to read full transcriptions and view full-size scans of the letters.

The Guest Room of the Wylie House presents the life of Seabrook Mitchell Wylie and each of the Wylie women’s experience of widowhood.

Sparsely written to or from in the earlier family letters, Seabrook’s voice became clear and emotionally powerful during the 1880s and 1890s. After leaving Bloomington for Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, in 1887, the family of Brown and Seabrook Wylie began to experience financial troubles, owing to the inconsistent employment of Brown and considerable debt accumulated by the family. Female impoverishment and a woman’s position within working-class life was caused by economic factors, but also familial conditions. Women depended on their husbands to financially support both themselves and their children. Still, much of the advice literature perpetuated the idea that mothers and wives were largely responsible for the frugality and financial security of their families, blaming women’s wastefulness of family resources as a major cause of debt.

The Wylie’s August 1869 edition of “Ladies’ Own Magazine”, the short-story “False and True” echoed this idea of the spendthrift, careless mother and wife, propelling her family into financial instability and destitution. The narrative followed that Effie, the neglectful wife, who had entrusted all her husband’s money into hiring domestic servants, rather than dutifully and selflessly laboring as the ideal mother ought to. As a result, the mounting debt of her husband became defined as her responsibility. In the text, Effie lamented,

“I have neglected all my duties as a wife; I have entrusted all my husband’s earnings to hired servants. I have even thought it too hard to make his evenings at home pass pleasantly. . . Can you forgive me!”

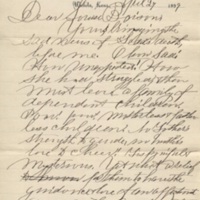

Seabrook’s own sentiments during the time of her husband’s financial troubles echo those of the fictional Effie. On December 30th, 1884, Seabrook wrote to her mother-in-law, Rebecca:

“Brown is having a hard hard time and he is so good to me. Instead of decreasing the debt now I am increasing and fear I can not see any of you until I help to decrease—or it seems I am a dreadful burden to everyone. Do not judge me too severely for I am suffering bitterly.”

"I have said had I not the babes I would work. As hard as it is I would separate from them for a while, any thing to lift this load and stand even with the world anyway." - Seabrook Mitchell Wylie, May 8, 1890

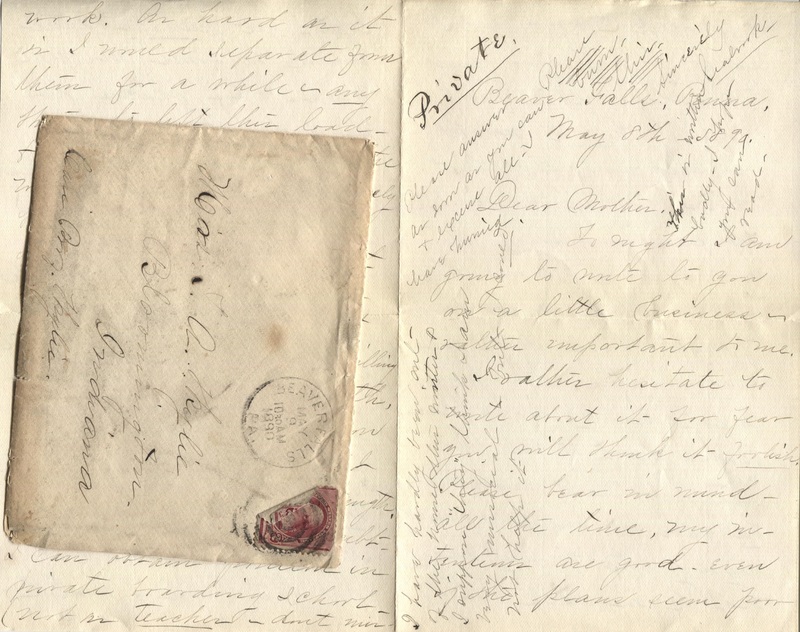

As a means of providing for her family and easing the guilt she felt, Seabrook decided to seek employment, violating the more deeply upheld notions of the “women’s sphere”. On May 8th, 1890, Seabrook composed a letter addressed to her mother-in-law, Rebecca Wylie. The chaotic scribbles of the page, the bold heading that reads “private” and the triple-underlined text, “please burn this.”, convey the distress of the troubled author. The letter reads:

“This cannot go on. Those bills must be met, especially where Father has gone security. We must meet them. I have said had I not the babes I would work. As hard as it is I would separate from them for a while, any thing to lift this load and stand even with the world anyway. I scarcely know how to tell my thoughts in the fervent words. You and Lou are the only two (save Aunt Lizzie) I would be willing to leave my babes with. If you were well I know you would help, but I fear your health and strength. I think, without doubt, I can obtain position in private boarding school (not as teacher, don’t misunderstand, but as one overseeing the domestic parts of the school).”

Within this excerpt, Seabrook made clear her intentions to enter into domestic service, a highly unusual decision for a middle-class mother. While this remained the most common and traditional employment option for women, domestic service remained unthinkable and inappropriate for the lifestyles of middle-class wives and mothers. Rather than tending exclusively to the comforts of home, husband, and family, working-class mothering required women to extend their labor beyond the “women’s sphere”. Seen a betrayal of a woman’s “natural” abilities, a mother laboring for wages rather than out of love was perceived as neglectful and outside the realm of “true” womanhood.

Despite all this, in 1890, Seabrook entered into live-in domestic service at St. Luke’s School in Bustleton, Pennsylvania, leaving the bulk of her motherly duties in search of peace of mind. Her eldest son, Theo, then twelve years old, remained in her care, tethering Seabrook to her maternal role. She wrote,

“My plan would be to take Theo and place him in this school, and there do some good for him, work for our board and his tuition. Thus our living expenses would be all cut off.”

The highly unusual nature of Seabrook’s “plan” reveals the desperation of the family’s situation and the distress of an overwhelmed and overburdened mother. Seabrook’s May 8th, 1890 letter continued:

“. . . Housekeeping was too much for me. I need a change, I am breaking down. . .Sometimes I feel like giving up every thing. If this change came we would sell off nearly all we have. As for my dear babes, I won’t think, only as I think of what I might accomplish for them in the future.”

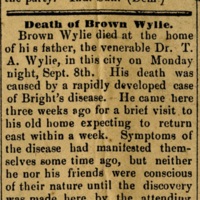

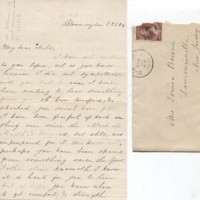

By August of 1890, Seabrook’s plan was in motion. Brown brought the couple’s three youngest children, Samuel, Reba, and Lawrence (then age eight, five, and three), to the Wylie House. Here, Brown intended to seek more gainful employment through family and Bloomington connections. And, shortly after his arrival, he was offered a Professorship of Chemistry in the State School of Mines in Rapid City, South Dakota. But on the night of September 8th, 1890, Brown Wylie died of “a rapidly developed case of Bright’s disease”, leaving Seabrook Wylie widowed, without a husband and apart from her children. She wrote of her husband’s death on November 15th, 1890:

“Death seems so strange to me now . . . His life was not half spent, his work not half done, and no year given him to brighten the memory of the dark ones, but taken just at the darkest hour. I can’t understand. Why was it! If I could know he was happier but no. Nothing left but to hope. These thoughts make me so restless. I try to drive them away and so often I feel I am only away from Brown as we planned first. I can not realize it. Perhaps it is best that I live so much in the today.”

Widowhood redefined wives, once bound by coverture laws, as a free and legally independent women. While still unable to equally access money, property, and social influence, American law held that widows were responsible for their own financial and legal identity. Legal codes required that a widow support herself on the basis of dower, customarily one-third of her husband’s estate, but often women sought further support from friends, relatives, or charities. Suddenly uncomfortably dependent or, perhaps, truly self-supporting, experiences of widowhood varied considerably depending on economic status, age, and maternal responsibilities.

Culturally, widowhood was synonymous with impoverishment, desolation, and destitution. Suddenly reassigned legal access into the public realm and roles of men, widows blurred the distinctions between the ideological male and female “spheres”, further complicating the idealized vision of maternal advice literature. To remedy this, Fictional portrayals of beggared, indigent widows in women’s magazines perpetuated commonly shared social perceptions, defining widows as defenseless and dependent. These same sentiments of widowhood reflect in the young writings of Maggie Wylie Mellette. On April 19th, 1865, following the death of Abraham Lincoln, Maggie wrote in her journal, “A dispatch came to town to day saying Mr. Lincoln is very ill not expected to live. Poor women. We have lost is almost as nothing compared with her. O to lose a husband. One she has lived with so long. What can be harder?”

Ultimately each of the Wylie women would come to lose a husband. The differences in their experiences of loss reveals more individualized, varied realities of widowhood. While many women did experience widowhood as devastating, others found independence and strength in their new roles – or at least something in between.

In 1884, Louisa’s husband Hermann died of heart failure at the young age of forty-four, leaving her with two young children, ages eight and five. In her 1894 brief autobiographical statement, Louisa spoke of her loss:

“After ten years of married life, the beloved husband and father, the lamented teacher, was suddenly taken away by death at the beginning of a most congenial work in the Boys’ School at Lawrenceville, N.J. and the bereaved wife returned with her two little children to her father’s house in Bloomington.”

Fortunately, Louisa found abundant emotional and financial support in her family. Her mother wrote to her,

“One thing you have to comfort you and that is you and your dear children will always have a home as long as we have one, and we will all be glad to have you with us again.”

A site that had always represented loving care for her and her children, Louisa returned to the Wylie House, once again.

In 1896, Maggie’s husband, Arthur died of heart failure. Of Arthur’s death, Maggie wrote, “all the joy of live went out of my life.” The burdens of widowhood weighed most heavily on mothers of young children, still dependent on their care. This was not the case for Maggie. Widowed after her children had reached adulthood, Maggie left South Dakota and went to live near her son, Charles, in Pittsburg, Kansas. Following Arthur’s death, Seabrook wrote Louisa,

“Your letter containing the sad news of Mr. Mellette’s death reached me this Thursday. It does not seem possible! All the homes are now broken up except the dear old homestead, all mother’s children are left alone"

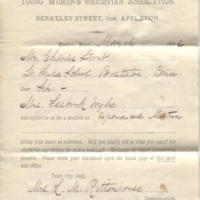

Still burdened by financial problems, Seabrook remained apart from her children, who continued to be cared for at the Wylie House by Rebecca, Louisa, and other “extended” mothers. In 1892, Seabrook found employment at the first Young Women’s Christian Association in Boston, as an “experienced matron”. A working mother away from her children and a widow, Seabrook’s losses forced her to question her social identity as a woman. Heart-wrenchingly honest, her letters from this period diverged from the ideals of maternal composure, exposing worry, anguish, and uncertainty. On February 15, 1896, she wrote to Louisa,

“I can not tell you how I feel. I feel as if all womanhood was gone. Even worse, as if I had never had any to lose. God help me now! I turn to you in all trouble. . .Kiss my darlings . . . Don’t let my babies near unkind things of their Mother. Your sister, Sede”

Hardly echoing the nineteenth-century ideal of mothering, following the death of her husband, Seabrook reunited with her three youngest children Samuel, Reba, and Lawrence, only once briefly. In April 24, 1899, at the age of 42, she died of heart failure in Springfield, Massachusetts. On April 27th, Seabrook’s uncle, George Hoss wrote:

“Oh how sad! How unexpected! How she had struggled, then must leave a family of dependent children. Poor! Poor! Motherless and fatherless children. No father’s strength to guide, no mother’s love to cheer! ‘Tis painful and mysterious. Yet what a relief for them to have the guidance and love of an affectionate grandmother and aunt. Yet what a task for you and your mother to care for, wish for and guide these dependent ones. May God help and strengthen you in this work.”

The image, taken on the stone wall at the front of the Wylie House, shows Louisa and Seabrook's children. Cared for and mothered by the united force of Rebecca, Louisa, and other household occupants, the children’s familial situation hardly echoed the nineteenth-century ideal. Rather, the Wylie Children and their caretakers represented an example of “extended mothering”. From left to right: Anton Boisen, Reba Wylie, Marie Boisen, Laurence Wylie, Samuel Wylie.

Confused on who's who? Take a look at the Family Relationship Chart at the end of this exhibit.